A candid talk with Sarah Feinberg and Richard Davey

The New York City Transit president is the frontline general serving where the trains meet the track, responsible for ensuring that the subways and buses run as well as they possibly can.

Those who serve in this role, like “train daddy” Andy Byford (now an Amtrak official), are more often transit wonks and less often political and policy operators. It’s not as though they labor in the shadows, but they have the rough and thankless job of working with the resources they’re handed to speed up construction, minimize delays and serve commuters better.

To get a better sense of the job, Vital City asked WNYC-Gothamist transit reporter Stephen Nessen to sit down with two former Transit presidents: Sarah Feinberg, who ran the Transit Authority from 2020 to 2021 — during COVID-19 and its related stresses — and Richard Davey, who did the job from 2022 to June 2024.

The following conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Stephen Nessen: The first question is about money, of course. Sarah, you were in charge during the pandemic when ridership plummeted. Rich, you saw the possible funding from congestion pricing get yanked away at the last second. While the operating budget now appears to have stabilized, with congestion pricing, the capital plan is now uncertain. Why do you think it is so hard to keep public transit in New York City funded?

Sarah Feinberg: I will contrast the two important moments. During the pandemic, the best thing we had going for us was Sens. Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand, Gov. Andrew Cuomo basically being able to go to the Senate, go to the House, and say, “We desperately need assistance, and not just for the MTA, but for all of the transit agencies across the country.” And so while we were extremely worried about finances — ridership was devastated — we had some white knights come to the rescue.

I would say the big difference with where we are now is that this sort of moment is very much a self-inflicted wound. And no one expects the federal government to come to the rescue on this one because when you set yourself up to actually solve some of your problems and then you rip the rug out from under yourself, no one’s going to come save you.

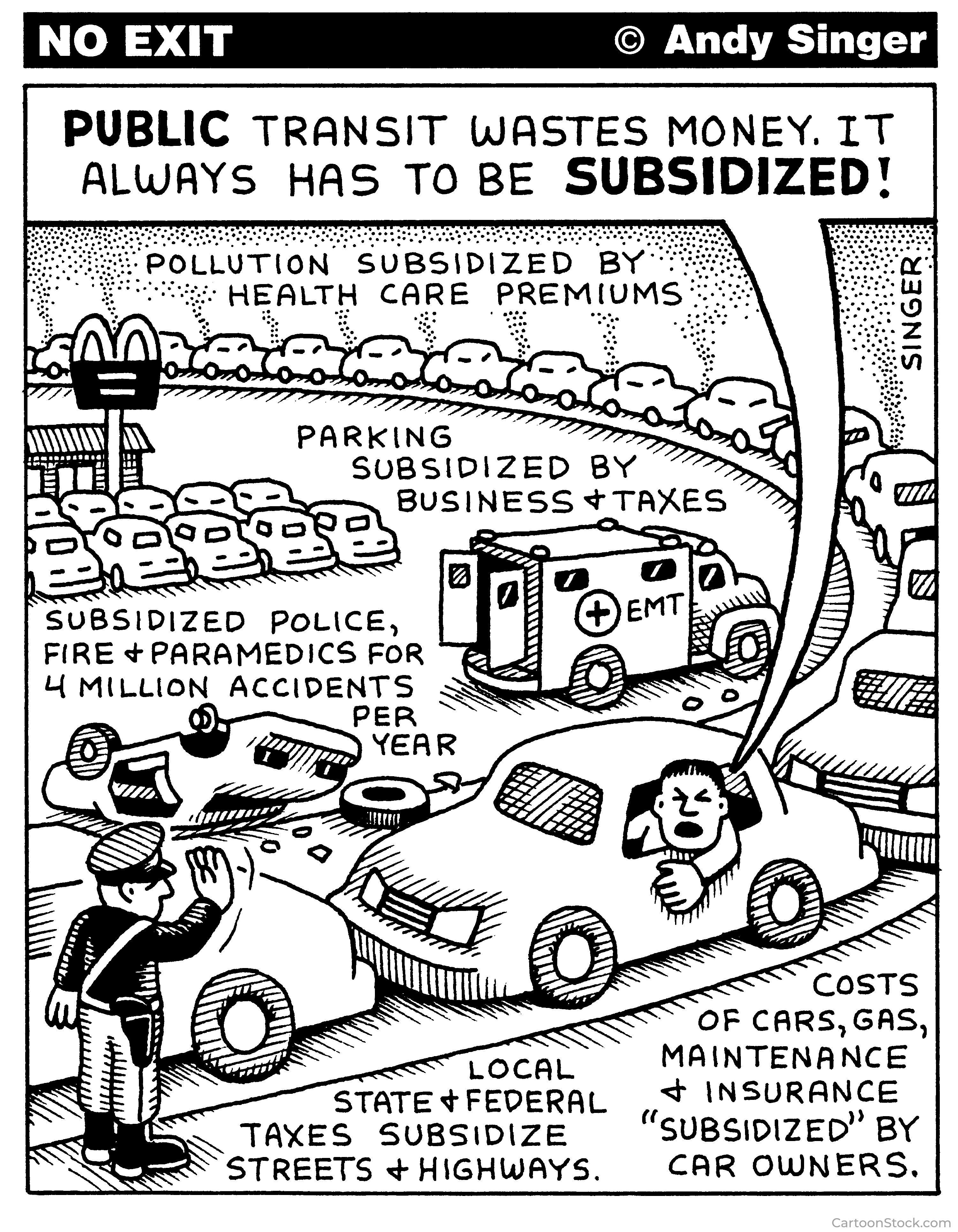

But look, it’s always been an uphill battle to get transit funded in the United States. Roads always win. Highways always win. Everyone wants to build an airport, and it’s very hard to get transit funded, and that’s nothing new.

Richard Davey: I’ll double down on what Sarah said. I mean, it’s not just New York, it’s really every major urban area. In fact, I think New York in many respects does it better than most because I think New York City does appreciate how important transit is to the city’s success, and that’s not casting aspersions at where I currently live, in Boston, or places where I’ve worked or consulted.

At least in my experience, there have been some who believe transit should be operated more like a business. And the answer is no. It’s a public good.

Taking a step back in the way-back machine: The private sector attempted public transit up until the 1940s, and it didn’t work. And cities and states and counties assumed that role as companies went bankrupt, and New York was no exception.

At least in my experience, there have been some who believe transit should be operated more like a business. And the answer is no. It’s a public good. Now, you can always be more efficient and do things better and learn from the private sector, of course, but fundamentally, it has to be subsidized. It just has to be.

In a place like New York, even before the pandemic, New York City Transit had among the nation’s best farebox recovery ratios, which means rate of self-funding. And New York was actually about as good as anybody else in the United States. And there are hundreds and really thousands of small transit agencies across America that are significantly subsidized.

So I’m not sure people think about it the way that they should. There’s that famous cartoon of someone driving a car and grumbling about public transit being subsidized, and there are all these signs showing everything associated with our roads and the federal highway system, which are subsidized, right?

I also think — again, this is not a shot at New York, this is just a general conversation about big infrastructure projects — there’s a reluctance to be really truthful about expenses. So whatever the price in today’s dollars, the Second Avenue Subway is going to be more expensive because they’re not going to break ground for another five years or eight years, and I think that confuses the public as well.

So I guess the upshot is it’s not a New York problem, although it is a problem in New York, that policymakers and electeds and others have to grapple with.

SN: Are there any reforms either at the legislative level or at the MTA that you would recommend to ensure the finances for the MTA are on sure footing going forward?

RD: I think what I found unique about New York City versus some other places I’ve observed is that the business community is pretty aligned behind funding transit. I mean, kudos to the business community in New York City for stepping up and supporting the payroll mobility tax. “Yes, tax us.” I mean, how often do you hear that? And that was a pretty big nut to close that operating gap that Sarah mentioned. To be able to guarantee reliability and frequency — which is, by the way, what customers generally say is their number one priority.

SF: I mean, it’s very hard to build anything in the United States. And I feel like the worm is sort of turning on this. It used to be that the most important conversation that needed to be had about a new project was making sure, whether it was housing or transit or anything else, that the community felt heard and people had the ability to weigh in. And I think while that’s important, we have clearly gotten into a place as a country where things get community-outreached to death, where the only folks who show up at the public meeting are the folks who have got all kinds of reasons why they don’t want the mixed-use affordable housing building six blocks from them or next to them or whatever.

I think even folks who have been appropriately respectful of permitting processes and environmental processes have realized over the last five or 10 or 20 years that we’ve dug ourselves into a hole, into a permitting process that’s almost impossible to build our way out of. So that needs to change. I hope it does change.

When I was at the MTA, I always felt that one of the biggest talking points that could be used against us getting more funding was for taxpayers to say: “But it’s not on time, it’s not on budget, the service isn’t that good. You built it like this when you could have built it like that.”

It’s always been an uphill battle to get transit funded in the United States. Roads always win. Highways always win.

A lot of folks will say, “You’re never going to get away from folks who have their complaints,” and I agree with that, but the work of getting taxpayer support gets a lot easier if you can say, “We were on time, we were on budget. We built the 700-foot station, not the 1,200-foot station. It might not be the prettiest thing you’ve ever seen. It might not have artwork that you gaze at while you’re waiting between trains, but it works and it’s functional and we built it quickly,” and New York’s obviously got a long way to go to be able to make that case.

SN: The MTA needs to do a better PR job for itself, is that part of it?

SF: It doesn’t come down to PR. What I’m suggesting is probably something that will take 10, 15, 20 years. What I’m suggesting is that the MTA has to be a much better fiduciary actor in terms of taxpayer dollars. The MTA has to go to their planners and say, “We’re not going to build the most beautiful station of all time. It’s not going to have perfect art in it. It’s not going to be bigger than it needs to be. It’s just going to be a basic station that’s going to provide service to the neighborhood.” And communities have to be supportive.

I think the MTA and the state have put themselves in a tough position. It’s been going on for way too long, which is: feed the MTA, feed the MTA, feed the MTA; feed the beast, feed the beast, feed the beast; and the beast isn’t always the best arbiter of the tax dollars. And I just think we should all be honest about it.

I think the MTA and the state have put themselves in a tough position. It’s been going on for way too long, which is: feed the MTA, feed the MTA, feed the MTA, feed the beast, feed the beast, feed the beast, and the beast isn’t always the best arbiter of the tax dollars. And I just think we should all be honest about it.

RD: One other comment on that, if I could, Stephen, and this is a conversation that’s probably going to happen relatively soon, which is the new subway cars. There was excitement about these accordion-style, open-gangway cars, which are “cool.” And people were like, “We should have them.” They cost more.

Back to Sarah’s point, it’s like if you don’t have an unending budget, there should be an honest conversation. We should have these new trains because London has them? What are you not buying as a result? Are you doing one less station with an elevator? Are you buying fewer cars as a general matter?

You’ve got to balance what you can afford and then what you aren’t buying.

I’m sure there’ll be a debate at some point in the future about whether you buy open-gangway cars or not, and I’m sure if it’s decided not to, someone will complain and say, “Why are we not a world-class city?” And the answer is, well, you can still be a world-class city. There are choices in front of you, and sometimes the MTA is under pressure to be all things to all people, and they can’t be that.

SN: There’s a capital plan coming up and a lot of questions about the funding from congestion pricing maybe not coming through in the end. What do you think are the right things the MTA should be investing in right now? Obviously, Rich, you don’t think accordion cars, but what should they invest in?

RD: It’s not that they shouldn’t. It’s that I’m not sure under the current budget. To me, it’s all about state of good repair. You don’t want the “Summer of Hell” to return. It wouldn’t happen tomorrow, but it would happen over 10 years if the investment isn’t occurring in state of good repair, the unsexy ongoing maintenance work that doesn’t get electeds and others to do ribbon-cuttings.

And the MTA, I think, has made a laudable commitment around accessibility, but that’s not a state of good repair. It should happen, to be clear, but that’s not a state of good repair. The Interborough Express (IBX, a light-rail project backed by Hochul that connects parts of Brooklyn and Queens) is not a state of good repair project. And Second Avenue Subway is not state of good repair. And elevators for customers who have been waiting for decades for accessible transit are not state of good repair.

You don’t want a future where a customer who is disabled can finally get on an elevator and get down to a subway station and have their train breaking down too frequently. You know?

SN: Just switching gears for a second, because I’ve been a reporter during both of your tenures: I have followed a lot of the conflicts, whether it’s the pandemic or labor strife, spike in crime, assaults, homelessness. What did you learn from them?

SF: I mean, when I think about my time at Transit, I recall that literally within three weeks of when I started, the city was being shut down. I started on March 2, and we shut the city down on March 16.

So there were many, many days where it was less about running a subway system and a bus system and more about communicating to the public what we were doing to keep people safe and how they should be behaving, or who should be out and about and who should be staying home; handing the governor plans that would literally give him the ability to shut the system down if he had to use it as a tool to keep people home; talking to spouses who had lost their husband or wife, or figuring out how to plan a memorial service for hundreds of people.

So when I think about what I learned at Transit, it’s not really like, “Oh, boy, we’ve really got to get those signals going.” We should, we have to, but that wasn’t really driving me when I showed up every morning.

RD: See, I had it easier, Steve. I think for me, I observed one thing and then was surprised about another. So the observation: I think I knew it coming in, but what was really sharpened during my tenure is how important the subway is to New York. Everybody I met up and down the economic scale, whatever demographic, had a New York City subway story. Everyone. When I took the job, the MTA communications director told me, “The media only covers two things: the weather and the subway,” because they affect every New Yorker basically. And he wasn’t that wrong.

The thing I think that surprised me, and this is probably in part impacted by COVID, is how much the job wasn’t actually related to public transit, or running an operation, but mental health.

Mental health is a huge issue for New York City, for other cities, but New York City in particular, with the sanctity of the subway system being such a public place where all walks of life convene.

Most of the folks struggling with serious mental illness are not violent. The vast majority are not violent. And I applaud the MTA. I think there was a moment when I started where folks internally said, “That’s not our job. It’s not our job,” and I give credit to the leadership for saying, “It doesn’t matter if it’s our job or not, we need to embrace this responsibility.”

I think crime’s important to address, but that’s actually, to me, not the issue. The most high-profile incidents that people were concerned about were largely due to underlying mental health crises.

Mental health is a huge issue for New York City, with the sanctity of the subway system being such a public place where all walks of life convene.

SN: Given the limited resources of the MTA, what is the number one thing you think they should focus on right now? Is it headways, fare-beating, mental health even?

RD: I think it’s the mental health question because it does have a detrimental effect on the long-term health of the city and certainly the system, and the employees, by the way, because they’re also getting assaulted, and scared, in record numbers. And that’s certainly not good for the system by any stretch. These are people who just want to come to work and are otherwise being exposed to this.

Then it’s just like the everyday slog of focusing on maintenance and state of good repair. Again, not one momenbt will collapse the system, but years of neglect will, and just keeping folks’ eye on the ball on that.

SF: I think that’s exactly right: It’s state of good repair and it’s mental health. And I think, look, there are folks in the press corps, many elected officials who will say that there’s too much of a focus on crime and mental health and homelessness and those experiencing a mental illness crisis in the system. And I think the fact that you have two of the most recent presidents of Transit both saying it is either the number one or tied for the number one issue really says a lot.

I used to try to explain my focus on this in this way: For New York in particular, if the transit system is not a sacred space, then the city will fall apart and it will fall apart slowly.

If you get to a point where you do not feel safe using the system to get to work or putting your child on the system to go to school, or you are just exhausted by asking yourself, “Should I switch cars? Should I bail on this train and go for the next one? Do I feel like I’m okay on this platform?” — that is exhausting.

You don’t have to look forward to your commute, but it should feel stable and it should feel safe, and it should feel like it can be trusted. And we’re not really in that place right now.

And ask any woman in the city, men have to do it too, but women have to do it twice as much. And that is the kind of stuff that will turn people to vehicles and to cars. And if that happens, we’ve lost the central business district, we’ve lost Manhattan, we’ve lost Brooklyn, we’ve lost big chunks of the city because the city just will stop functioning.

That leads you right to why there was so much frustration this summer when congestion pricing got canceled. It wasn’t just about all those billions. It was like we’ve gone to this critical place where the city is not working. It’s not walkable. It’s not livable for families who are in Manhattan and Brooklyn. And by the way, same in Queens and the Bronx too. I just happen to spend a lot of time in Brooklyn, and I have to spend a lot of time in Manhattan because of school and kids and work. There are many neighborhoods where you just cannot, you would never walk your stroller across the street. You would never think you can get across with the light because cars are running the red all the time.

You don’t have to look forward to your commute, but it should feel stable and it should feel safe, and it should feel like it can be trusted. And we’re not really in that place right now.

SN: Do you think it’s worse than when you were Transit president?

SF: No. No, no, no.

I think it’s better now than it was. I feel safer and more confident. I feel safer and more confident with my daughter. There are moments when you feel like it’s slipping away a bit, but I think it’s better than it was.

SN: Last question. Would you guys recommend the job to your friends?

RD: Without hesitation, 1,000%.

SF: It’s the best job in transportation in America, hands down. I told Polly Trottenberg once that running the Department of Transportation in New York City was the best job in government, but then I was like, “Oh, no, actually it’s the second-best job. The first best job is running New York City Transit.”

SN: You probably sleep better now without worrying about those midnight calls about disasters.

RD: A midnight call would be early.