Street-involved youth feel unprotected by police.

It’s June 2019 in the courtyard of an East Harlem public housing development. It feels like everyone is out—enjoying the sun, smoking weed. Our team is spread out on wooden benches doing hour-long interviews with young gun carriers. Suddenly, an older man on a bicycle appears: “That’s some police shit!” he yells out. Then, even louder: “They with the Feds!” Now he is making a scene.

Those of us on the research team who have been involved in the streets and gang networks have spent years building our credibility. We’re never tested like this in our Brooklyn neighborhood. It’s a shock. One of us jumps up and walks closer to the man: “Do we look like some cops? Do we look like some snitches to you?” The exchange escalates. We have to help each other stay calm and remind ourselves why we’re out here. We’re still finding a balance between our long-held street identities and our newfound roles as social science researchers studying young people and guns. For now, with balance hard to come by, we pack up for the day. Using our networks, we make some calls to figure out who the Big Homie is in the neighborhood, knowing it’s information that will come in handy.

Back in East Harlem the next day, a light drizzle is falling. We head straight to the housing development’s courtyard, where the man with the bicycle is standing with three others. They’re shocked to see us back so soon, but we keep calm. We tell them who we are, what gives us the credibility to do the work we’re doing. We say we know who the Big Homie is and let them know how we were able to find that out. We explain that the project we’re a part of could be a big step towards changing both our neighborhoods and us. And we tell them the power research gives us: to tell our own stories—instead of having them told by academics or other people who haven’t lived our experience—and to have a chance to shape policies that affect our daily lives.

Researchers have spent upwards of 30 years talking about shooters but not talking to or with us in any significant way.

The man with the bike says he gets it now and admits that, yesterday, he felt left out of something powerful taking place in his neighborhood. For our part, we get back to our interviews, despite the rain.

We share this story because it is a lesson in how delicate the balance of integrating research and the streets can be. It exemplifies the lengths we’ve had to go to prove to street networks and policymakers alike that this work is possible, but that it can only be pursued with this level of honesty and depth with the significant involvement of team members who are street-involved. And it takes real sacrifices and risks to do it. Researchers and policymakers have spent upwards of 30 years talking about shooters and people with street involvement, but not talking to or with us in any significant way. Our research was an effort to change that.

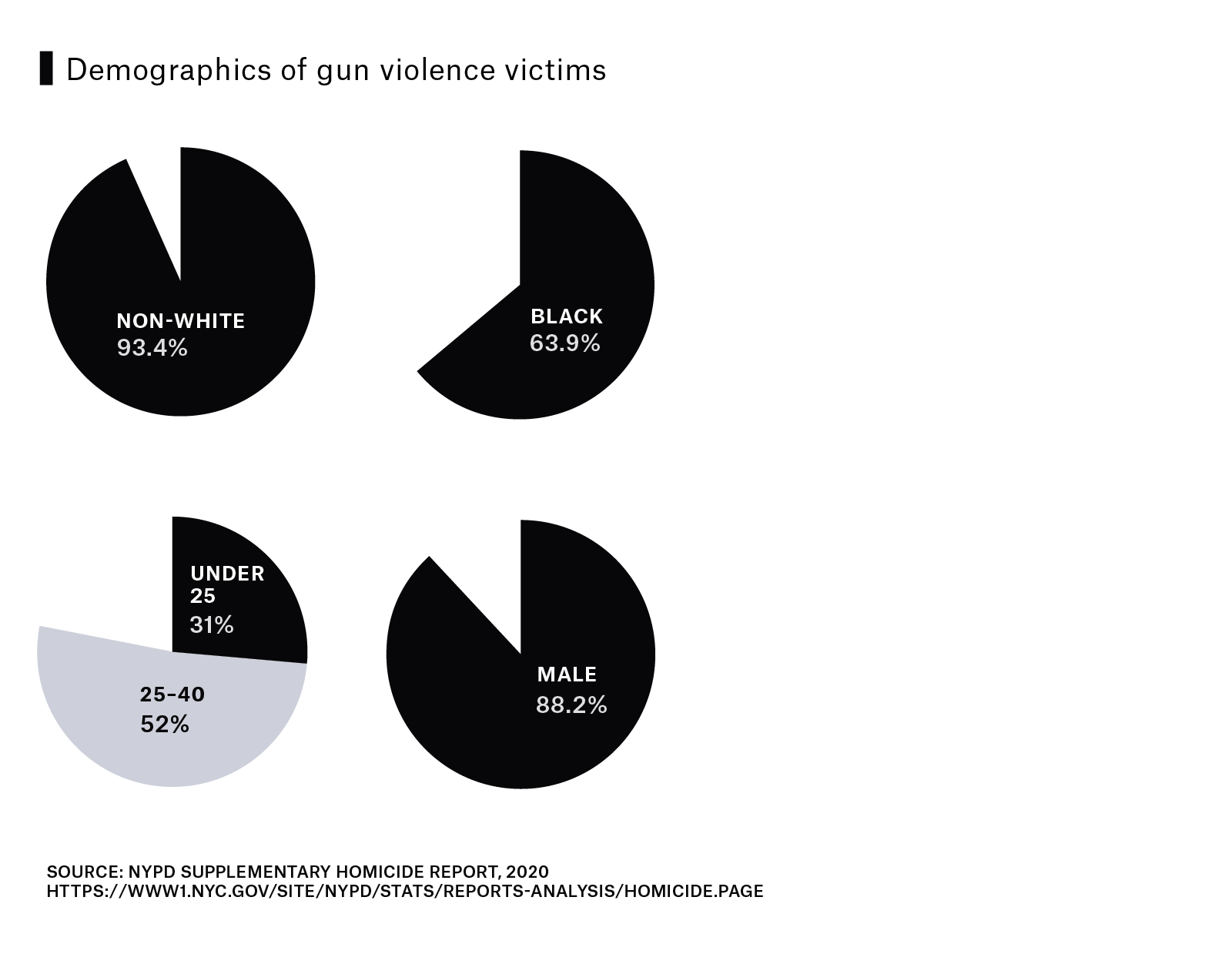

For more than a year, beginning in the summer of 2018, our team conducted in-depth interviews with 330 New Yorkers between the ages of 16 and 24 in areas with high rates of gun violence—overwhelmingly young Black men living in public housing. The goal was to learn from them why, and when, they carried guns. Led by the Center for Court Innovation, the field research was conducted almost entirely by people with deep experience in the generally hard-to-reach networks we were attempting to access and relied on intensive periods of trust- and credibility-building in each new neighborhood we went into.

To be eligible, participants had to either have carried a gun or been shot or shot at. In what follows, we offer a brief window into their experiences, which are also our experiences. It’s an effort to make good on the promises we made that day in the courtyard. In neighborhoods scattered across the city, decades of policy decisions have shaped the conditions where young people are living, and dying, by the gun every day. We want our research to help keep those young people alive—our brothers, cousins, friends and sons.

First, some context. Many of the young people who participated in our study grew up in atmospheres where violence, or the threat of violence, was ever-present. More than four of five had been shot or shot at, and two-thirds had been attacked with a weapon other than a gun. Almost 90 percent had experienced a friend or family member being shot, and 70 percent had witnessed someone getting shot. People are shocked every time we present these numbers. And their surprise surprises us. We live these numbers every day.

A second critical factor: Not feeling protected by the police. One participant explained, “cops aren’t there late at night . . . you’ve got to protect yourself.” Another voiced a common complaint: the police were around to harass them for infractions, but not for serious crimes: “There’ll be [people] out here getting killed and raped. They don’t be worried about none of that, but they be worried about somebody smoking a little bit of weed outside. . . . We feel like we can’t really ask them for help. . . . When there’s people out there actually getting hurt, they’re nowhere to be found.” In general, the participants in the study had widespread contact with police—almost all had been arrested, often multiple times, more than half before age 16. This was a major contributor to participants’ expressing vanishingly little trust in police; only 15 percent agreed police had good reasons for making arrests.

Some reported carrying guns because of a pervasive sense they could be victimized at any time—a kind of generalized fear: “I’m a paranoid person ever since I got stabbed. I come out of work and nobody’s after me . . . I still be lookin’ behind me.” Other participants felt a more localized fear—needing protection from people seeking retaliation: “I got shot and I been shot at. Niggas I done robbed, I done took niggas’ chain. I done embarrassed grown-ass men. So I need one. I’m a female. Niggas want to shoot at you.” Finally, many pointed to a fear of being killed by police as a primary reason for carrying: “They’re picking off people for no reason. . . . It’s not a regular person I gotta worry about. I gotta protect myself from the people who are made to protect and serve us. And that is the most scariest thing in the world.”

“You do violent things or robberies when you got no other way out.”

Participants’ choices over when to carry could also be influenced by frank calculations of the finer operations of structural racism. One participant explained how his decision to carry was directly related to how responses to violent crime vary by neighborhood: “If I’m chilling in [my] area, it’s mandatory; don’t play with your life. But if I’m going to 125th or Union Square, it’s no need for that . . . ‘cause you ain’t gonna shoot me in Union Square. Well, you probably will, but I will get to the ambulance better than over here. . . . I feel like if the police see me laying on the floor in my area, it’s a ‘pull out their phones, see what time it is’ moment.” Another pointed to the perception of a complete institutional abandonment: “It's like we're already in the trap, with the system and with the law. Everybody's going to jail, there's no jobs, minimum amount of services provided for us, healthwise. People tend to do things . . . and they get caught up in the system. . . . You do violent things or robberies when you got no other way out. That's all it is now. It's all you know.”

The street-involved youth of color that we talked to are caught in a double-bind: they described feeling unprotected from other gun users by police (whom participants also fear) while simultaneously punished for self-protecting through gun-carrying. The trauma this generates exists at the community level, and it factors into nearly every gun-related decision these young people make: “One thing I can say: they don’t make it nice for a Black man to live out here. You gotta make your own heaven out here.”

We conclude with two overarching recommendations. The first is that policies and programs must start by contending with the sobering conditions these young people live in, learning from them what they need and how best to cooperate on delivering it; failing to do so will only compound these young people’s mistrust and vulnerability. The second is that responding to the problem of young people and guns with more policing will only increase these young people’s fear, trauma and sense of imminent harm, thereby producing more gun-carrying. Given the wholesale distrust of police—the perception that they are intent on harassing young people of color over minor transgressions but have little interest in protecting them from serious violence—strategies to ensure safety and foster healing must emerge from the community. ◘

Special thanks to Rachel Swaner and Elise White for their support in researching and writing this article.

Further Reading

‘Gotta Make Your Own Heaven’: Guns, Safety, and the Edge of Adulthood in New York City.