Can cities find new ways to address disorder?

Disorder is a vexed topic.

For some, minor misbehavior (for example, farebeating, shoplifting, disorderly conduct) and physical decay (trash, graffiti, boarded-up windows) are signs of a city on the brink, a society at risk of descending into lawlessness.

For others, “disorder” is a loaded term, a social construct and a racist dog whistle. For these observers, disorder is just an excuse that the powers that be use to manage the comings and goings of marginalized populations.

This debate has been raging for forty years, ever since George Kelling and James Q. Wilson published their seminal “Broken Windows” essay in The Atlantic. The gist of Kelling and Wilson’s argument was that social and physical disorder, if left unchecked, could lead to more serious crime.

In the years that followed, police departments across the country interpreted the broken windows theory as a rationale for expanding the enforcement of low-level offenses — and credited this strategy with helping to reduce local crime. At the same time, critics blamed broken windows for a host of ills, including stop-question-and-frisk practices that were found to be unconstitutional and increases in incarceration which damaged many Black communities in particular.

While there is not a lot of good polling data on the topic, there are some indications that urban residents are increasingly concerned about quality-of-life conditions in their neighborhoods — and that perceptions of disorder are linked to growing fears about crime. Many pundits attributed the electoral victory of New York City Mayor Eric Adams to his decision to focus his campaign on crime and disorder. In a similar vein, the recent recall of San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin, who announced that he would not prosecute quality-of-life crimes, was interpreted as a referendum on disorder, with a clear electoral lesson: the voters care.

The politics of “disorder” are heavily influenced by the threat of policing. If policing is the only answer to disorder, then our current debate will simply continue ad infinitum, with cities lurching back and forth between catastrophism and permissiveness depending upon who has won the most recent mayoral and DA elections.

Is there a way out of this box? Is it possible to forge responses to disorder that do not rely primarily on law enforcement? What if cities could discourage anti-social activities — for example, public intoxication, urination, minor theft, graffiti, disorderly conduct — in the subways, parks and other public spaces without relying on policing, prosecution, fines and jail?

In an attempt to answer these questions, we asked a handful of experts for their opinions on how to combat disorder without relying first and foremost on the police.

The following responses have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Talib Hudson is the founder of The New Hood

It is possible for cities to address and discourage antisocial activities without relying on the coercive power of the state. It is well established at this point that informal social control is much stronger than formal social control. There are three ways that cities can harness informal social control:

- Setting the Norm means that cities can use their powers to establish desired standards. The New York City subway system doesn’t have the graffiti of the 1980s because the MTA instituted an innovative strategy of first cleaning “tagged” cars and then never allowing a “clean” car to go into service with visible tags. The lack of visibility discouraged artists from tagging cars.

- Empowering Local Residents means providing civic education, micro-grants and other resources for neighbors to take care of each other.

- Supporting Private Sector Efforts means making sure business improvement districts have what they need to keep areas clean and leveraging partnerships where available.

We don't currently have evidence proving that these actions will definitely solve the problem, but they provide opportunities for change without the collateral consequences of the courts. This doesn't mean that there isn't any role for police, prosecution, fines and jail, but they should only be the option of last resort.

Daniel McPhee is the executive director of the Urban Design Forum

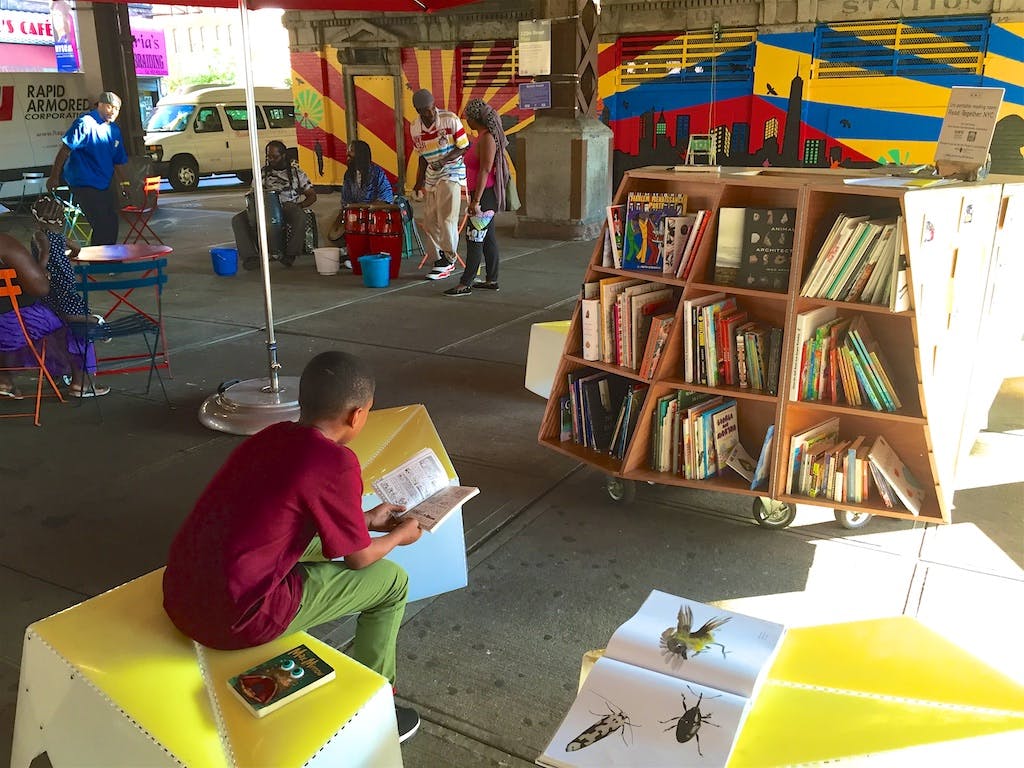

Ultimately, I think that public space stewardship and on-site management are the foundations for safety. Attendants and ambassadors who are always out can spot issues quickly and address them, from graffiti to public intoxication, and only engage law enforcement in the most serious circumstances. Public bathrooms are just one tool at their disposal; street ambassadors, sanitation services, landscape maintenance and public programming like music and dance all serve to bring many "eyes on the street."

Our current policies and budgets related to business improvement districts and conservancies have effectively balkanized the city into areas that are clean, safe and well-managed, and areas that are not. Wealthy neighborhood landowners can fundraise, pay for on-site security and sanitation, improve landscaping and public space design and address issues before they get severe. Other neighborhoods have small stewardship organizations, if any, limited funding and limited staff.

If we think that neighborhood stewardship is an important piece of safety, then government can do a much better job of blanketing the city with stewardship organizations. This means mapping who lacks access and supporting the development of new organizations with both funding and capacity-building trainings.

John E. Eck is a professor of criminal justice at the University of Cincinnati, where he teaches graduate courses in crime policy and crime prevention.

I routinely walk around my city. The unpredictable person who hangs out in our library branch does not scare me, but the students riding electric scooters on sidewalks do. I see a lot of disorder, but not everywhere.

Disorder has a long and ugly history in the United States. Real estate developers, urban planners and politicians have been decrying “blight” since the early 20th century. With the great migration of African Americans from the Southern states to Northern cities, "blight" became a code word for undesirable people. In the 1950s, the rhetoric of blight fueled urban renewal. In the 1980s, “blight” became “disorder,” became linked to crime, and enforcement became the solution.

So what should we do about “disorder?” There is no single direct solution — disorder covers too wide a range of activities to address with a generic remedy. However, problem-solving and situation approaches have often proved useful for finding tailored solutions to particular problems. Often, tailored solutions require those who own and operate places to take care of the messes they allow or create. My condominium building, for example, changed the ground cover to an aesthetic surface that dogs avoid, thus reducing the dog excrement problem. No dog walkers were arrested.

If cities want to take on the varied problems lumped under disorder, they should provide incentives for property owners to keep their property clean. The city should repair its sidewalks. And those electric scooters ridden by students on sidewalks? The city permitted the scooter companies to sell their machines. Therefore, the city should revoke the permits, or force the companies to regulate their scooters. Nobody needs to be arrested, stopped or frisked.

Hannah Meyers is the director of policing and public safety at the Manhattan Institute

There are many creative ways to inspire pro-social behavior in public places, such as greening empty lots, adding street lighting, engaging neighborhood watches and employing CCTV cameras. Likewise, citizens enjoying civil activities in shared spaces promote lawful respect among others. But the full success of these measures relies on the expectation of robust criminal justice responses — the underlying deterrent to bad conduct.

New York City’s subway system provides an illustration of these dynamics. Rampant antisocial behavior, crime, and violence was ultimately only curbed by the conscientious and systematic increase in proactive policing in the early 1990s. And patrolling infractions like loitering also allowed police to prevent larger crimes by, for example, discovering weapons on low-level offenders and deterring others from entering the subway system armed.

Further, these gains created “peace dividends”: less policing, prosecution and incarceration were necessary as an expectation of good behavior became the norm. However, in the past few years we’ve seen a reversal. As local prosecutors ceased to prosecute farebeating and dismissed many more cases overall for a variety of reasons, police withdrew further on arrests and summonses and the city methodically detained fewer offenders in jail, levels of antisocial behavior shot up underground and have not decreased — even as ridership returns post-pandemic.

Greg Newburn is the director of criminal justice at the Niskanen Center Richard Hahn is the senior fellow for research, criminal justice, at the Niskanen Center

The typical civic response to antisocial behavior in the United States is grudging tolerance punctuated by periodic enforcement. In the intermittent instances when sanctions intended to deter unwanted behavior are imposed, they are often perceived as arbitrary and heavy-handed. Unsurprisingly, strategies built on disproportionate, sporadically applied penalties fail to create stable and tolerable community conditions.

Cities should develop and test responses to antisocial behavior that can be applied with consistency and predictability. These would include deterrence through sanctions proportionate to the harms they mean to prevent, but would typically exclude fines and jail after prosecution. Cities might try strategies that employ the principles behind what we call a “TAIL” approach to order maintenance:

- Triage: Responses should match the rational capacity of the person subject to the response. Diversion to services may be more efficient and fair for people who present mental or substance misuse problems. Coercion may be necessary for sufficiently rational people, though it should be designed to create temporary disruption rather than lasting harm.

- Alternatives: Investments in public spaces could allow people who might engage in antisocial behaviors to avoid them, and generate benefits that exceed their costs. For example, open public lavatories like those in London might reduce public urination. Easily accessible donation boxes might discourage people from giving to panhandlers but encourage them to contribute to supplemental social services.

- Inconvenience: Passive strategies like “target hardening” can make public spaces less vulnerable to antisocial behavior. Meanwhile, some active sanctions could delay or embarrass troublemakers without taking away their freedom or money through traditional enforcement. For example, cities might consider requiring people who evade the subway fare to wait on the train platform for an hour rather than fining or arresting and prosecuting them.

- Location: Cities should concentrate enforcement resources in areas where problem behavior generates intolerable costs. Officials should make clear what types of behavior will lead to sanctions. In these circumstances, cities should be prepared to follow through on enforcement threats. At the same time, temporary “zones of tolerance” might also reduce the costs of antisocial behaviors imposed on unwilling bystanders and make the allocation of social service resources more efficient. For example, authorities might tolerate homeless encampments in certain disused city spaces to provide both a stable living location for people unwilling to accept public shelter and an opportunity to address needs among a spatially concentrated population.

The goal of responses to antisocial behavior should not be to eliminate it everywhere but to suppress such behavior to levels at which communities, businesses and individuals can exert informal social controls to keep it in check. Cities looking to reduce antisocial behavior and enforcement costs should consider testing responses rooted in the “TAIL” approach described above. As always, implementation should be informed by local needs, and responses should be evaluated frequently and improved as necessary.

Felipe Vargas is the vice president of programs at The Doe Fund

We should respond to disorder by investing as much energy and resources into rehabilitation as has been placed in policing. Marginalized populations — including people experiencing homelessness and incarceration — need access to economic opportunity. When given a place in mainstream society, they have a vested interest in preventing its decay and disorder. If we are looking to remove police from the approach, employment is the single greatest deterrent to recidivism. I would know — I’ve lived this experience firsthand.

Social enterprises run by human-service nonprofits are an implementable solution that accomplishes all of the above. They train and employ people who have historically survived on the fringes. They provide community services that improve quality of life, such as sanitation, graffiti removal and rat abatement. And they generate revenue that goes back into the programs helping people in need.

Jim Burch is the president of the National Policing Institute

As Talib Hudson shared, there is power in informal mechanisms that create or maintain social order. Communities can create and maintain social order through design, innovation and responsive services in areas including sanitation and maintenance. Research tells us that it is possible to deter criminal activity without arrests or citations, but the deterrence benefit isn’t sustainable without continued police presence, at least intermittently. “Policing” should not be conflated with “law enforcement” — there is much that police can contribute that does not involve arrest or citation.

An excellent example is the Arlington Restaurant Initiative, a creative collaboration between restaurants and bars and the Arlington, Virginia, police department. The program was initially proposed by a 21-year veteran of the department, who realized that the agency’s enforcement-first approach was costly and was not solving the problem of alcohol-related crime and disorderly behavior. Instead, the Arlington Restaurant Initiative has built a training and accreditation program for local bars and restaurants, empowering the business community to be the first response. While the approach still requires police engagement, it reduces alcohol-related disorder without necessarily increasing criminal justice system involvement through arrests. Relying on the police alone, or an enforcement-first solution, is counterproductive and costly for all involved, including taxpayers. It’s time we put some effort and thought into approaches that address disorder in systematic and sustainable ways.

Sarah Picard is the director of the Center for Criminal Justice Research at MDRC Center for Data Insights

Those concerned with rising disorder in the streets and subways of New York City should pay close heed to the retreat of public and political support for bail reform. Fueled by recent increases in violent crime across the city (both real and imagined), the bail reform debate has degenerated into a partisan stalemate. Rollbacks to a more conservative approach are likely to continue to be enshrined in state law despite a lack of consistent evidence connecting bail reform with increased violence.

On public disorder, we still have an opportunity to choose a different, less contentious path. Decades of evidence demonstrate that disordered environments breed more serious crime, primarily by driving a retreat from public life by residents. But New York City’s reliance on “impact policing” has yielded a widespread erosion of police legitimacy among residents of marginalized neighborhoods.

The presence of armed and uniformed police — whether they are practicing stop-and-frisk or playing midnight basketball — does not protect citizens from the 24/7 strain engendered by poorly lit, abandoned areas and petty crime. A better approach would be substantial, citywide investment in the repair and maintenance of abandoned areas, accompanied by incentives to nonprofits and businesses to help revitalize public life in these areas. This would free up the police to focus their efforts on the resolution of violent cases, thereby repairing police legitimacy in areas with high rates of violent crime.

As an applied researcher, I believe that new approaches to disorder should be bookended by evaluation efforts to gauge whether our intuitions regarding what might work play out on the stage of real life. Prior to implementation, we should make projections about long-term impacts and plan to mitigate the inevitable trade-offs between safety and liberty. I can’t help but wonder if we have already missed a major opportunity: the city has not created explicit structures to constrain public marijuana use, especially by youth, prior to legalization.