The famed sociologist talks about his recent research and how precarious life can be for those who spend time on Rikers Island.

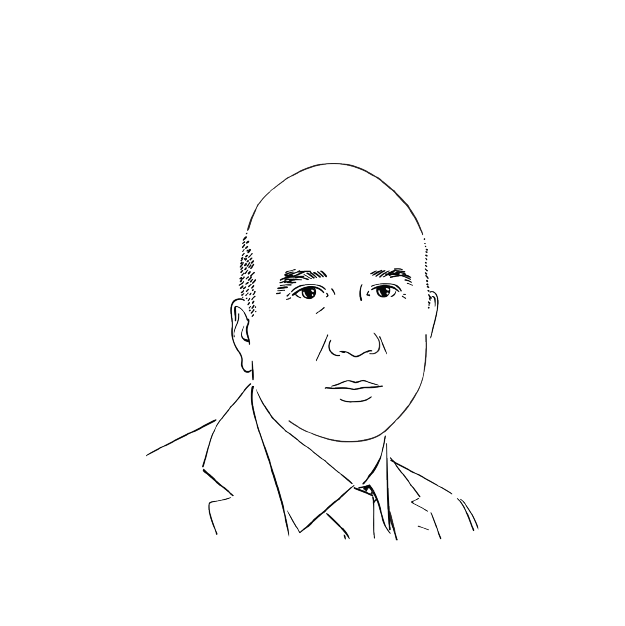

Bruce Western is one of the nation’s most prominent sociologists. At a time when the study of people in jail and prison was unfashionable or nonexistent, Western forged an area of rigorous study to understand who the people who end up incarcerated are, what effect incarceration has on their life course and how they live once they are released. His decades of work have filled in a picture of people who are often living in precarious economic circumstances, without stable housing, employment or the kinds of supports — for example, health insurance — that permit a fruitful life. These conditions fold in on one another and make it exceedingly difficult for many individuals to forge a productive path in life.

Western has written extensively about his findings, combining, unusually, a scholarly rigor and a deep sense of humanity with a graceful pen. The result is a compelling and persuasive body of work. His most recent book, Homeward, an exemplar of his felicitous style, tells the story of a range of people returning home to Boston from the Massachusetts prison system and how they fare in resuming life on the outside.

Western is currently a professor of sociology at Columbia University. In July 2025, Western will assume the presidency of the Russell Sage Foundation, a philanthropy devoted to research in the social sciences.

Vital City sat down with Western this summer to discuss his work and, in particular, his reflections on who is held at Rikers Island and how those stays have affected their lives. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Vital City: Your research has really defined the frame in which many policymakers now operate when thinking about incarceration and the criminal justice system. How did you get interested in these issues and how has your thinking evolved?

Bruce Western: I started out as a student of labor markets, labor market inequality and poverty. I didn’t study crime or criminal justice policy at graduate school. And I was a comparativist; I was looking at differences in patterns of unionization across Western Europe and the United States. And I think even then part of my motivation was to try and understand something about American exceptionalism, why America and its politics and economy have charted such a different path from Western Europe and from Australia, the country I grew up in. Over time in my first few years after graduate school, I really wanted to develop a research agenda that was much more focused on the United States, and partly I wanted to understand America better. And sort of by accident, I think, I had a great friend at graduate school, Katherine Beckett, who was working on crime policy and incarceration. And we were having a bunch of conversations about what makes America different. And sort of flippantly one day she said, “Well, America doesn’t have a welfare state like in Western Europe. It’s got a penal system.”

Coming to know people who are working in prisons and people who are incarcerated in prisons really drove me to develop a deeper understanding of what was going on. Why did America choose this as a way of responding to problems of very deep and very harsh poverty and centuries and centuries of exclusion?

And so we began to try and think systematically about that idea and the kinds of research questions it presented. And so that’s what started me down that path at the very beginning. But as I began to get into this research too, I began going into prison to teach at the invitation of my Princeton colleague, Patricia Fernandez Kelly. Patricia was teaching at New Jersey State Prison in Trenton, and so I started to teach there as well. And I think it was actually that experience of teaching in prison that really drew me into the work of trying to understand American incarceration and its connections to poverty and racial inequality and injustice. And so I would say it grew out of this.

Honestly, coming to know people who are working in prisons and people who are incarcerated in prisons really drove me to develop a deeper understanding of what was going on. Why did America choose this as a way of responding to problems of very deep and very harsh poverty and centuries and centuries of exclusion? Why was this somehow the answer to those problems?

Vital City: Those twin questions that your colleague asked you at the very beginning about, well, “America doesn’t have a welfare state, but it does have this penal system,” seems reflected even in this most recent paper on Rikers, where in some ways you suggest the solution is: Let’s try to cobble together a social safety net. You are nearing the end of this big project looking at people who have been held at or passed through the City’s jails. Tell me a little bit about how you came to work on this project — and what were the main things you wanted to find out?

Bruce Western: I think one of the big impulses for this project on Rikers and people moving through the criminal courts in New York more generally — some of whom were detained, but some were not — was knowing the work that MOCJ (the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice) was doing on behalf of the City’s effort to close the jail and make a reality the City’s stated policy to close the jail. We conducted interviews with about 300 people going through the court system starting just before COVID-19 in 2019. I was hopeful that research at that time could help this process and try to bring to light a dimension of the social experience of people who are involved in the system, that I think was kind of well understood but had been difficult to document.

The thing I learned when I arrived in New York in 2017 — and I was coming off a prison reentry study that was very focused on the City of Boston and the Massachusetts Department of Correction — was that in New York there was this very different policy and research environment. The policy community to me seemed very sophisticated, very highly attuned to research — certainly MOCJ was, and was doing creative policy work.

But the kinds of data involving the policy process were very much structured by the system itself. And policymakers in the City, I think particularly in the criminal justice area, had a terrific window on the dynamics of the jail population, patterns of policing and arrest, and the court process. I felt we knew far less about things like, well, what sort of health problems are people struggling with? What are their patterns of householding and housing? And I think householding as an idea is kind of distinct from housing status. But I thought that was important. And how all of these things — health, housing, employment, poverty status — how were they co-occurring, how do they go together, and with what impact?

I was thinking about a very old tradition in research on jails. They viewed the jail specifically as an institution that was very proximate to low-income communities and the social problem of poverty. The underlying question for me — and I’m not entirely sure we had visibility on it from the kinds of data that were being analyzed — the basic question for me is how much jail incarceration, how much of the action in the criminal courts was really related in a pretty direct way to socioeconomic insecurity? And so in this thinking, there’s a piece about serious crime, but a piece of it is about something else.

Vital City: You sketch how precarious life is for the great majority of people who you interviewed, the high percentage who are in shelter right up until they’re in jail. Maybe half of them are employed, but you use a rather benign word, “informally,” meaning that it’s not stable, it’s mainly in cash. And they don’t have health insurance — the health insurance itself sort of feeds into these other issues of people who are vulnerable with respect to mental and physical issues. And then, just chillingly, the violence of childhood trauma continuing through adulthood. Something like 25% saw someone killed, something like 45% suffered from childhood sexual abuse. What surprised you or what confirmed things that you knew?

Bruce Western: There were things, I think, that our research team saw in the field, there were patterns that were quite unexpected for me. The insecure housing and being unhoused and contending with all of these problems in public space because you don’t have a private household to retreat to, there’s no sanctuary in your life, I think exposes you to the attentions of police. And that is kind of the thread, I think, that runs through a lot of our findings. And it was surprising because the template I was bringing to this research was the experience of people coming home from prison in Massachusetts to Boston. That was the other big field study I’d done immediately prior to this, and housing insecurity was a big problem for people coming home from prison. But it was a much greater problem in New York, I think, than it was in Boston.

Vital City: And perhaps because one population was a jail population by its nature more volatile, coming in and out, and the other is a prison population. Is that an aspect of it?

Bruce Western: I think that’s a big part of it. And I think the proximity of the jail to poverty is much closer than the proximity of the prison. And I think the affordable housing crisis in New York City is a very deep social problem that, housing specialists aside, I’m not sure has been fully absorbed in other social policy domains. There is something very fundamentally dysfunctional about not having a place to stay, really a private household, in which there’s a whole network of social support that can be your sanctuary.

I think the affordable housing crisis in New York City is a very deep social problem. There is something fundamentally dysfunctional about not having a place to stay.

Vital City: Your report says something like in the month before incarceration, three quarters of the people had been in some kind of unstable housing situation. And then as you look at the numbers as people get older, by the time they’re in the 44-and-up category, something like over half of them had been at shelter at some point. Could you talk a little bit about this idea that you introduced a little earlier about householding being something different than unstable housing?

Bruce Western: The household is not just the physical residence in which you live, it’s also that network of people with whom you live. You are living often with kin, with family, in intimate relationships that are capable of providing a very deep and varied kind of social support that’s just very, very difficult to get in any other setting. In the Greek, the household is the oikos — and we get the word economy, it’s derived from the original Greek word for the household, the oikos.

Economy is derived from the Greek word for household because this is the way human needs are met. Human needs are met through the intimate relationships of kin and householding, this network of people who know you best. And so I think there’s enormous social welfare potential in private households. And I think this is partly how we should be thinking about the challenge facing people who are housed very insecurely, who are often unhoused. It’s not just about putting a roof over people’s heads, but is there a way of providing a kind of social support that is suffused with the affect and caring that can attend to people as individuals and can attend to their individual needs? This was the sociologist Erving Goffman’s great insight about the asylum; it was the bureaucratization of human need. And this is why carceral settings are capable of so much brutality, because they can’t individualize their response to human need, whereas households can.

Vital City: It’s as if it’s not simply the money, but the human network that makes it come alive, with a big emphasis, an underscore, on the human/humanity part of it.

Bruce Western: Yeah, I think that’s exactly right. I know great work is being done around supportive housing and there are some great supportive housing programs. And as we think about this challenge also in a world in which we’re hoping that the jail population in a city of eight and a half million people is going to be three and a half thousand or less. There are going to be people who have acute housing and other needs and we will have to find innovative ways to meet that challenge. And we must find ways of supporting that human connection, I think, for people in ways that households often do. I think that is kind of a policy challenge we’re facing.

Vital City: You wrote this fantastic book, Homeward, which reads like a novel about people coming home to Boston from Massachusetts prisons. And one of the things that comes through so starkly is how every group has a network of some kind. White people coming home may have an economic network through unions and getting jobs, other ethnic groups may have familial networks that provide other kinds of connections. One of the big things that came through was that sense of how alive and important the network is, and not just the bureaucracy.

Bruce Western: I think that was a very striking thing for me from talking to people in Boston. In policy conversations, we’re so focused on systems and programs and agencies, but the reality that people were living after prison was their relationships with family and friends and neighbors — that occupied the space of people’s reentry experiences. And I think there’s a big implication for policy, and that is the people who are doing that caring work, all of that supportive work on behalf of all of us, they should be targets of policy too. They should be the beneficiaries of social welfare efforts that are trying to support people’s community reintegration.

Vital City: At the end of your study, you draw some pretty tight connections between what it is that you found and the ways in which, not just that suffering can be relieved, but that human lives can be advanced. It seems as if you’re finding the levers that there are in the pieces of a social network that has been cobbled together. Could you just talk a little bit about how you see what those opportunities are and how we actually get from your recommendations to them being implemented?

Bruce Western: Yeah, I think for me, job one — I would frame it as supporting people moving through the criminal court process — is trying to ensure that they have a secure material platform from which to begin to conduct their lives in a way that’s predictable for them. And so that means housing, health care and income support. I think that’s the foundation on which predictability in daily life depends. I think, for younger people, pathways to economic opportunity that seem attainable and realistic — I think that’s really important. I think trying to distinguish in our policy approach between responding with force to instances of serious interpersonal harm in communities and responding in a nonblaming way to people in crisis. I think that is another component of a policy response to people who are now finding their way into our criminal courts.

Job one in supporting people moving through the criminal court process is trying to ensure that they have a secure material platform from which to begin to conduct their lives.

So material foundation, building pathways of opportunity to young people and developing different kinds of frontline response in situations of emergency, which may be serious interpersonal harm or it may be people in crisis in public space. And to me they seem to be components of a different kind of paradigm. The problem is not fundamentally crime and public safety, but having some sort of policy paradigm that’s geared toward human thriving in our cities, and where people are living in close proximity, where public space is well trafficked. And that’s our real challenge. How do we promote that human thriving in those kinds of settings?

And so I think that would be my answer as a start. How do we get there? As a matter of politics, I think, it is a tough question. As a process matter, I think it is enormously important to attend to the challenges of community safety and people’s anxieties about their safety. I worry that in a lot of criminal justice reform conversations, we haven’t taken crime seriously enough. And I think we’ll often say that, well, of course what we are talking about is safety, in talking about reducing jail populations or prison populations or something. We are talking about safety. But then I think we have to be very direct in how we’re connecting the policy reforms we’re seeking to how communities in fact will be made safer, and we have to acknowledge the enormous social costs of interpersonal harm just as we acknowledge the enormous social costs of the harms that the system itself can create. So I think that’s an important part of feasible politics.

I think officials in the system have just an absolutely indispensable role to play in the process, and that goes for policymakers and line staff. And I look at a place like Rikers, which is just such a brutal institution, and I see unions fighting tooth and nail to defend jobs in which people are pulling two and three shifts and can be exposed to a lot of personal risk. Why is that a job worth defending? Is that what we want? Is that what a union wants for its membership? So I think line staff have an important part to play in that conversation. And of course, the communities that are really bearing the brunt of conditions of high crime, deep poverty and high levels of system involvement.

At Rikers, I see unions fighting tooth and nail to defend jobs in which people are pulling two and three shifts and can be exposed to a lot of personal risk. Why is that a job worth defending?

Vital City: Figuring out how to take the overarching point and divide it up into operational pieces in some ways is the challenge, right? We understand what we need to do, at least potentially. It’s a long fuse to say, “Let’s try and fix the social safety net because we know that, at the end of the day, that will ensure that people never touch the criminal justice system.” But that has to become operational to policymakers in order to change the way things are right now.

Bruce Western: I mean, I think that is one very concrete step that represents a qualitative shift in the policy response. On the safety net, I will say, so for the one year in COVID-19 relief when the child tax credit was operating, America came extraordinarily close to eliminating the problem of child poverty. Unbelievable. They did it for one year and they came within one vote in the Senate of making it permanent. So I also think change is possible in the safety net. I think we are in a very unusual time where even the Republican presidential campaign now is, in part, trying to speak to the economic anxieties of its working-class base in a very state-driven, cash transfers sort of way, and backing off from the market rhetoric of conservative politics that has prevailed since World War II.

Vital City: We’ve covered a great sweep of time. Looking back on the last 50 years and how far we’ve come — and looking forward to, yes, extraordinary challenges ahead — how optimistic are you about the possibility of making change, and what do you think the major impediments are that we have to address in order to change things for the better?

Bruce Western: I think change is possible, and I think we’ve witnessed change. My career has spanned the era of rising incarceration rates and very high rates of crime, and declining incarceration and very significant declines in crime. Clearly change is possible. I think, to me, right now in this election year, it feels that our core institutions are under tremendous stress. I think American democracy has always been very incomplete and very contested, but at this moment, democratic institutions are under almost existential stress.

And I think the rule of law, which holds enormous progressive potential, is also under extraordinary stress right now. Finally, the major challenges that are facing American society as a whole and not just the domains of urban policy and criminal justice policy, are rooted in something very structural that is also going on in other societies like ours, these forces are at work in other countries as well. These are the big challenges I think we’re facing.