What the data tell us

New York City’s jails are in a state of perpetual crisis, documented over many years in a steady flow of reports on the violent and inhumane conditions inside for both people in custody and people working in the facilities. Violence, unmet needs, sexual abuse, mismanagement, and the unsanitary and decrepit nature of the buildings themselves have all featured prominently in the news, in our own reports, and in the reports of the federal monitor overseeing the jails as the result of Nunez v. City of New York and Benjamin v. Maginley-Liddie, among many others. The entrenched nature of these problems is now in stark relief as the judge overseeing the Nunez case has ordered the parties to begin developing a proposed structure for a federal receiver. Appointment of a federal receiver to take over control of the jails is an extraordinary measure, and the fact that New York City is the closest it has been to one in its history is a marker of both the seriousness of the problems and their resistance to change.

Yet while we know things are bad, the picture of conditions in the jails remains woefully incomplete. The information that does exist is fragmented — held in different locations, sometimes by different entities, which often conflict with one another. While there are exceptions, much of it is made available only in PDF format, making it much more labor-intensive to identify trends, and there are often inconsistencies in when it is made available. And, of course, some information becomes public only when it makes it into a monitor or news report, which makes it less likely that it will be tracked consistently.

With all of that said, here we present a picture of conditions in the jails as we know them: Who’s being held, what it’s like to be inside, and who’s responsible for oversight.

Who’s inside?

As is true around the country, in New York City, people of color are vastly overrepresented in the jail population. Currently, almost 9 in 10 people in custody are Black or Hispanic, although they represent only 5 in 10 in the city overall. The disparity is most acute for Black people, who comprise more than half of the jail population yet less than a quarter of the city population. The jail population is also overwhelmingly male and the majority are older adults.

The people held in New York City jails also have many often overlapping needs, with the majority being people with low incomes and often people suffering from physical or mental illness. A quarter will be homeless or face housing instability upon release, and 85% will be eligible for Medicaid, indicating high levels of poverty.

The health and mental health needs of people in the City’s jails are inextricably linked to conditions inside, as access to services can be inconsistent or sometimes entirely lacking. A recent report alleges that people with severe mental illness — who make up 1 in 5 of the jail population — are often locked in their cells for days rather than provided with treatment and support. People in custody are more than twice as likely as the general population to have a mental health concern: More than half of those in jail have one, compared to 1 in 5 in the city. Roughly a quarter have alcohol and/or opioid use disorder, and many have chronic medical conditions.

The jail population is substantially lower than it was at the start of the monitoring period, although it has increased from its COVID-19-induced low in 2020. Pretrial detainees — meaning people who have not been convicted of any crime — continue to make up the vast majority of those incarcerated. A much higher proportion of those detained pretrial have been accused of committing violent crimes than in years past.

People in custody continue to remain in jail for far longer than in earlier years, with the average length of stay continuing to hover above 100 days in fiscal year 2024. Long jail stays can have a devastating impact on the physical and mental health of people in custody and strain their ties with their families, communities and employment or school. Where, as in Rikers, conditions are poor, longer lengths of stay increase the time that people will be exposed to those conditions — including an increased likelihood of victimization.

What’s happening inside?

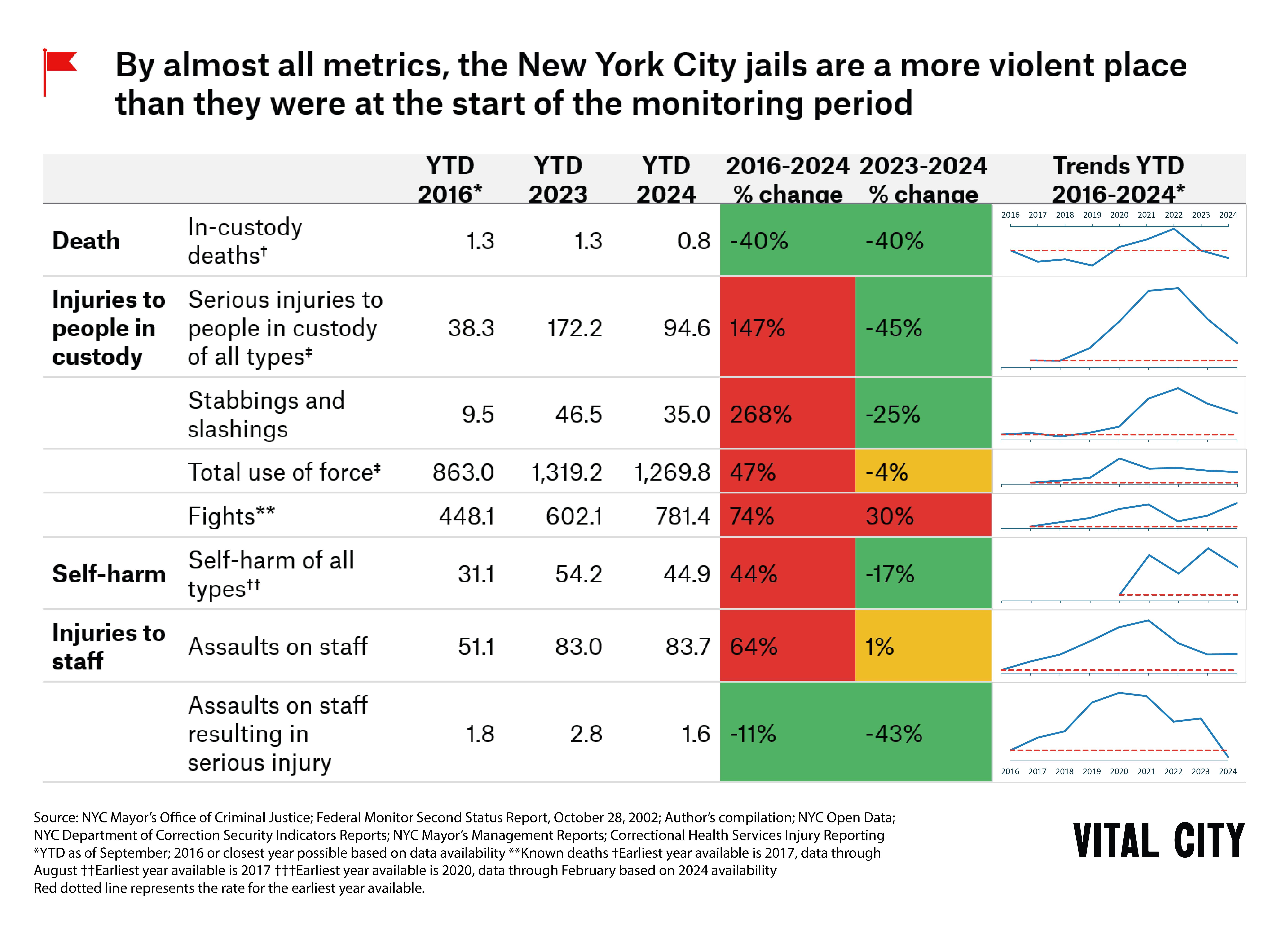

What we know about conditions inside the facilities on Rikers makes the excessive stays of those held inside that much more appalling. The consent decree enacted at the end of 2015 as the result of Nunez v. City of New York was intended to address unconstitutional levels of violence in the jails. Yet by almost all metrics, the jails are a more violent place than they were at the start of the monitoring period. Violence peaked in the period during and immediately following the COVID-19 pandemic, and while there has been improvement since that time, the pace of improvement has slowed dramatically and in some cases started to rise again. As in several areas relating to conditions inside, information is sometimes absent or suspect, as noted by the federal court. In those instances, we have noted those issues with a red flag.

The rate of stabbings and slashings remains alarmingly high, 43 times higher than the low in fiscal year 2008, and more than four times higher than at the start of the monitoring period. Yet even this may be an undercount — last year the Nunez monitor cast doubt on the veracity of the Department of Correction’s stabbing and slashing reports. History shows that stabbings and slashings can be controlled — for more than a decade, the rate was kept below 5 per 1,000 people in custody, compared to almost 60 per 1,000 today.

Despite the high levels of violence in the facilities, the extent to which there are consequences for acts of violence are not clear: What little information is available on staff accountability comes from the Nunez monitor, and we know of no reliable source of data on accountability for violence committed by people in custody. The monitor has previously called out the department for being overly reliant on retraining, corrective interviews and counseling at the expense of more formal discipline, and these continue to comprise the majority of accountability measures imposed for misconduct related to use of force.

Alongside the violence inflicted by people in custody and staff on those incarcerated, the rates of self-harm tell their own disturbing story about conditions inside the jails. Data is not available prior to 2020, so it is not clear how current self-harm rates compare to years past, but what we do have suggests an overall trend upward since it started being reported. Both the court and the Nunez monitor have flagged self-harm as an area that must be addressed by the department, with the monitor flagging both the failure of staff to respond appropriately and the failure of the department to retrain staff and/or enforce policies regarding self-harm and suicide prevention. The Nunez monitor also noted a troubling uptick in suicides in recent years.

Compounding these problems is the failure of Department of Correction staff ensuring that people in custody make it to their scheduled medical and mental health appointments. At present, only half of scheduled appointments are completed, compared to more than three quarters of medical appointments and two thirds of mental health appointments completed in 2018. It is notable that an increasing proportion of visits are being missed due to the failure of the Department of Correction to bring people in custody to their appointments: Departmental nonproduction accounted for 79% of missed medical appointments and 67% of missed mental health appointments in the most recent quarter available.

Even more disturbing are allegations detailed in a motion for contempt that the department is falsifying records — claiming that people in custody had refused to go to their appointment when they were unaware the appointments even existed or had been coerced into signing refusal forms. These allegations are also borne out in a comparison of data on missed medical appointments produced by the Department of Correction and by Correctional Health Services (CHS). In June 2024, the most recent month available from both sources, the department reports that 6,796 appointments were missed due to refusal by the person in custody. During that same time period, CHS was able to verify 3,402 refusals, half that number.

Unsurprisingly, then, complaints related to medical care are routinely the most common type of grievance filed by people in custody, accounting for roughly a quarter to a third of grievable complaints over the past few years (to be considered grievable, complaints must fall into one of 29 set categories defined by the Department of Correction). The number of complaints filed has remained high, yet a City Council analysis found that only 15% of those complaints are ever formally resolved. Also alarming are the continually high numbers of complaints regarding sexual assault and abuse, many of which are never reported under Prison Rape Elimination Act mandates — including some that the department acknowledges should have been.

The department also receives hundreds of grievances, a quarter related to the environmental conditions in the facilities. For almost 30 years, the department has operated under a consent decree related to environmental health conditions pursuant to the court decision in Benjamin v. Malcolm and modified by subsequent orders over the years. The monitor’s most recent quarterly report continues to paint an appalling picture of the facilities, with most housing areas lacking in basic sanitation.

The conditions exist despite a rich budget and high levels of staff. When inflation is accounted for, 2023 Department of Correction spending was almost identical to spending in 2014 despite a 45% decrease in the jail population and a 24% decrease in staff.

The department’s actual spending is also heavily influenced by uniformed overtime costs, which remain astronomical. It is unclear what drives these costs, however, since they do not seem to be driven by the actual number of uniformed staff at the department or the number of people they are tasked with supervising.

Who’s watching?

These conditions persist in spite of the numerous entities at multiple jurisdictional levels tasked with oversight of the department. All of these entities have, at various times, in varying ways, attempted to hold the department accountable for its failure to improve conditions for those held and working in the jails. To date, none have been successful in effecting substantial enough change to create a safe and humane living environment.