How the new Manhattan traffic plan would work

Before Gov. Hochul's 11th-hour reversal Wednesday attempting to indefinitely postpone the reforms,* flows of traffic into Manhattan were set to be transformed with the June 30 advent of congestion pricing, a first-in-the-nation policy charging automobiles a fee to enter Manhattan at 60th Street or below, whether they come via bridge, tunnel or surface street.

It’s been a long road, with many car owners, who already grouse about the cost and frustrations of driving, upset about the prospect of paying $15 a day to enter the center of the nation’s largest city. Meanwhile, many New Yorkers who rely on subways, buses and commuter rail are excited about the prospect of infusing more money into public transit while combating often crippling traffic in the central business district.

Public polling on the topic has yielded mixed results. In 2019, a Quinnipiac Poll said New York City voters opposed the idea of congestion pricing, 54% to 41%. A 2019 Siena poll showed 52% support among New York State residents, including somewhat stronger majorities in the five boroughs. A Siena poll released this month found that 63% of New York State voters, including 64% of New York City voters, oppose the new charge, while about a third of each support it.

What follows is a cribsheet on congestion pricing and how it came to be.

Who came up with the idea?

In 1952, Columbia economist William Vickrey, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize, came up with the concept of congestion pricing — suggesting that, to limit overcrowding and respond to supply and demand, subway fares increase at peak times and in high-traffic parts of the system and be lowered at other times and in other places. He and others soon suggested applying the concept to car and truck traffic, with Manhattan, an especially traffic-plagued island at the center of the nation’s largest city, the natural place to give it a go.

Why did it take so long?

New York City’s first concrete attempt to make the rubber meet the road happened under Mayor John Lindsay, who proposed limiting cars in Lower Manhattan and tolling all East River crossings. In the 1980s, Mayor Ed Koch’s transportation commissioner warned that “drastic” steps were necessary to comply with the federal Clean Air Act, and proposed options that included charging fees to enter certain parts of the dense little island. Given the politics and complexities of implementing such a scheme, none went anywhere. Other global cities, most notably Singapore, London and Stockholm, would go on to implement their own plans.

In New York, the idea got its first big 21st-century push under Mayor Mike Bloomberg, who in 2007 proposed an $8 fee to enter Manhattan. “Just take a look at our kids in some of our poor neighborhoods who go to hospitals with asthma rates that are four times the national rate. Every day it gets worse,” said Bloomberg. “It will clean up our air and it will improve our economy.”

There will be no tollbooths: Automated license-plate-reading cameras at 110 locations will photograph vehicles’ license plates (if they are not illegally obscured or fake).

The mayor stepped on the gas, with Gov. David Paterson and Senate Majority Leader Joe Bruno riding in passenger seats — but in 2008, powerful Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver stood athwart history yelling “stop!” He said he was responding to opposition in his caucus, which included many suburbanites. While a minority of New Yorkers own cars and most, especially low-income residents, rely on mass transit to get around, it’s also true that a transit charge hits some city dwellers and suburbanites who, because they work in transit deserts or at odd hours or in particular professions, feel they have little choice but to drive.

Another decade passed, with terrible New York City traffic persisting or even worsening — and in 2017, the state’s public transit system, both the subway and commuter rails, seemed to just fall apart, suffering from a “summer of hell.” Then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo concluded that the MTA needed more capital funding and better management. In 2019, Cuomo won landmark state approval for a congestion pricing plan in that year’s budget; then-Mayor Bill de Blasio seconded the motion and began pressing for progress.

Plans stalled under then-President Donald Trump, whose Department of Transportation refused to grant the approval needed to ensure that New York remained eligible for aid from Washington. The White House viewed the fee as just another tax on working people; COVID disruptions also helped pump the brakes.

When the pandemic receded and administrations changed, the federal process unstuck under President Joe Biden. Ultimately, after public comment and an exhaustive environmental review, the federal government gave its approval in mid-2023, then the MTA gave its final assent this March. While New Jersey and others are in federal court suing to stop the plan, purporting to defend the interests of hard-working commuters, the finish line — meaning the start date, when cameras turn on and fees begin to be charged — is in sight.

The billion-dollar-a-year question is this: Why was there so much resistance to this favorite idea of transit wonks? It’s not too hard to explain the inertia over more than a half-century: Nobody likes a new tax or toll — and the public has proven especially resistant to a novel fee that’s never before been tried anywhere in America. Suburban drivers are a powerful constituency, and those sensitive to their interests, especially in state government, steadfastly resisted reform. So too, did some bedfellows in the city: Working-class communities in the South Bronx, worried about traffic, emissions and high asthma rates, were staunch opponents.

The fight over congestion pricing is also interwoven with the decades-long struggle over reshaping city streets to greater advantage bikes and pedestrians. Conflicts over bike lanes, pedestrian plazas, speed cameras and the like often felt like battles in a larger culture war, pitting impassioned New York City constituencies against one another.

What changed in 2019 is that a governor and others saw the opportunity to present congestion pricing as a partial answer to growing frustration with public transit.

In New York City, a majority of households, and an even lower share of low-income households, don’t own a car and rely on public transportation. According to the Community Service Society, just 2% of outer-borough working residents in poverty drive in as part of their daily commute.

How will it work?

The congestion pricing plan has twin, closely related objectives: to reduce stubbornly high automobile traffic in Manhattan, and to raise at least $1 billion, and ideally more, in capital funding annually to support public transit. MTA officials expect the plan to reduce the number of vehicles entering the central business district by 17%.

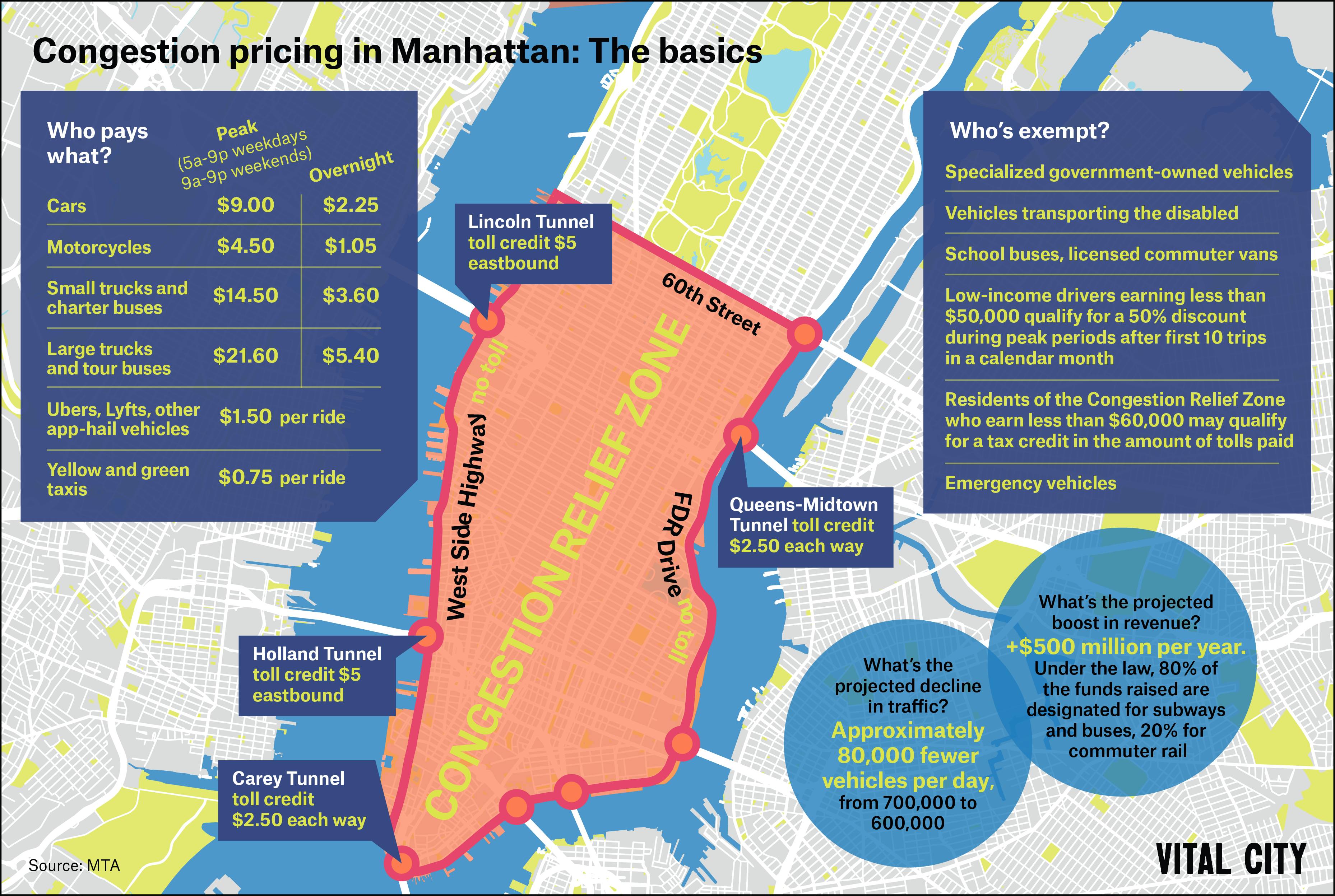

The program’s final details go like this: Cars will pay $15 to enter Manhattan at 61st Street and below during daytime hours (5 a.m. to 9 p.m.), and $3.75 during off-peak hours (9 p.m.-5 a.m. on weekdays, and 9 p.m. to 9 a.m. on weekends). At peak times, motorcycles will pay $7.50; small trucks and charter buses, $24; and large trucks and tour buses, $36. Ubers, Lyfts and other app-based for-hire vehicles will charge $2.50 per ride, and yellow and green taxis (and neighborhood-based black car services), $1.25 per ride.

There will be no tollbooths: Automated license-plate-reading cameras at 110 locations will photograph vehicles’ license plates (if they are not illegally obscured or fake). Aside from the cabs and for-hire vehicles, the rest of the vehicles will be charged once a day, upon entering the zone.

The fee will not apply to those using the FDR Drive and West Side Highway. And drivers who enter via four tolled tunnels will get “crossing credits,” that will reduce the congestion fee by the amount of the existing toll. Those who drive from one point in the zone to another in the zone will pay nothing.

An MTA study from last November projects a 17% reduction in the number of vehicles entering Lower Manhattan.

Who’s exempt?

In the run-up to final approval, many constituencies, including New York City public employees, those with medical appointments and those with electric vehicles, all lobbied to be exempt from the fee. Exemptions wound up being quite narrow: city-owned buses, school buses, private commuter buses, New York City-owned fleet vehicles, emergency vehicles and vehicles transporting people with disabilities. Low-income drivers making less than $50,000 a year can apply for a half-priced daytime toll, a cut rate that will kick in after the first 10 trips in a month.

When does it begin?

People who drive into Manhattan, either for work or pleasure, remain resistant, and so are many politicians. They call it a tax on working people — likely referring to the 100,000-plus outer-borough residents who drive into Manhattan for work. But in New York City, a majority of households, and an even lower share of low-income households, don’t own a car and rely on public transportation. According to the Community Service Society, just 2% of outer-borough working residents in poverty drive in as part of their daily commute.

Cuomo, a prime mover of the plan in 2019-2020, has had a change of heart — saying that given the city’s need to recover from COVID, “we must seriously consider if now is the right time to enact it,” and Mayor Eric Adams, wary of a new tax on some outer-borough residents, is decidedly unenthusiastic. A half-dozen lawsuits in federal court seek to delay if not totally derail the program; one, filed by the state of New Jersey under Gov. Phil Murphy, claims it violates New York Law and the U.S. Constitution.

If the plaintiffs, whose best shot seems to be convincing judges to force additional environmental reviews, don’t get their way, automobiles were set to start paying the fee on June 30 — that is, until Hochul, a longtime advocate, suddenly slammed the brakes on this highly consequential real-world experiment.*

* This explainer was updated on June 5 to reflect the unexpected postponement of the policy by Gov. Hochul and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.