Research is clear: Violence tends to be a crime of passion,

not economic desperation.

“Violence is an expression of poverty.” That’s how a recent Chicago mayor explained the cause of what is, now, the top concern of voters in so many U.S. cities. The argument is simple: If gun violence is caused by economic desperation, just end economic desperation. President Lyndon B. Johnson argued this was the “only genuine, long-range solution.” As Father Greg Boyle in Los Angeles put it, “Nothing stops a bullet like a job.” This idea is intuitive, widely believed and fundamentally optimistic (since one thing the government is quite good at is writing checks). Unfortunately, it is also wrong.

That the mayor’s statement focused on violence is no accident: It’s violent crime, especially gun violence, that drives the public’s concern about crime overall. Anti-poverty policies wind up having surprisingly modest impacts on this problem because most violent crimes aren’t motivated by profit, they’re crimes of passion instead — including rage.

Shoplifting, fraud and theft — the sorts of property offenses that account for 80% of all crimes — are maddening. But violence — especially gun violence — is something different. Gun violence is devastating. Gun violence affects everyone. Victims aren’t the only victims. The trauma ripples out to the whole community. And the fear of gun violence causes people and businesses to flee from the places affected. The result can be vicious cycles in which shootings drive out residents and economic activity, begetting more shootings, begetting more flight.

Economists can even quantify all the ways in which crime and the fear of crime harms people's lives, both tangible and intangible, and put those harms into a familiar unit of measurement: dollars. University of Pennsylvania professor Aaron Chalfin and Columbia University professor Justin McCrary have shown that the 0.2% of all crimes that involve gun violence account for something like 70% of the total harm of crime on society.

The distinction between crime overall, which is equivalent to looking at property offenses (since they’re 80% of all crimes), versus violent crime, turns out to be important because the two types of crime turn out to have different causes. We can see that in how both types of crime respond to changes in people’s economic conditions.

There are countless examples where benefits reduce property crime but have no impact on violence.

A lot of the best evidence on this question comes from studying the effects of government anti-poverty programs, which provide people with either cash or in-kind benefits (food, housing, etc.). The reason is that there are so many “natural experiments” baked into the American social safety net. Program benefits change over the years, they vary across states, in different places they get paid out at different frequencies, and often these programs aren’t funded at a level where every income-eligible person gets benefits. So, unfortunately, equally disadvantaged people can wind up getting very different levels of government help.

The best available evidence suggests that jobs and transfer programs have little, if any, systematic relationship to violent crime. That’s true for jobs programs or social programs for low-income populations in general, or for specific higher-risk sub-populations like people exiting prison. Policies to alleviate material hardship, as important and useful as they are for improving people’s lives and well-being, do not by themselves appear to be sufficient to also substantially alleviate the burden of crime on society.

There are countless examples where benefits reduce property crime but have no impact on violence. For example, in places that pay benefits monthly, we see relatively higher rates of property offending towards the end of the month when people are more economically desperate, but not more violent crime. When Alaska hands people a big annual lump-sum payment from the Permanent Dividend Fund, property crime falls but violence appears unaffected. We see increases in charges for income-generating crimes among people who lost eligibility for Supplemental Social Security (SSI) benefits upon turning 18 — but no change in the number of charges for violent behavior.

One might wonder if giving people in-kind benefits (rather than cash) might have different preventive effects. Policymakers who are nervous about how recipients spend cash income often believe in-kind programs might be truly more helpful to people. But with respect to impacts on violence, studies of food stamps (SNAP) and housing programs suggest that this does not seem to be the case (Medicaid health insurance being the one notable exception).

Prioritizing jobs or cash assistance for the people who are truly at highest risk — like those exiting from prison — could have bigger preventive effects. But decades of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of the sort that provide “gold-standard” evidence in medicine, from the 1970s to the present, suggest that this doesn’t seem to be the case.

Can changing an entire community’s economic conditions all at once, rather than those of just a few people, have bigger effects on violence? Apparently not. Almost every study that looks at this question finds that when macro-economic conditions improve in the country as a whole, or within a given state, property offending goes down, but violent crimes don’t. If anything, the most serious violent crimes — murder — might even increase.

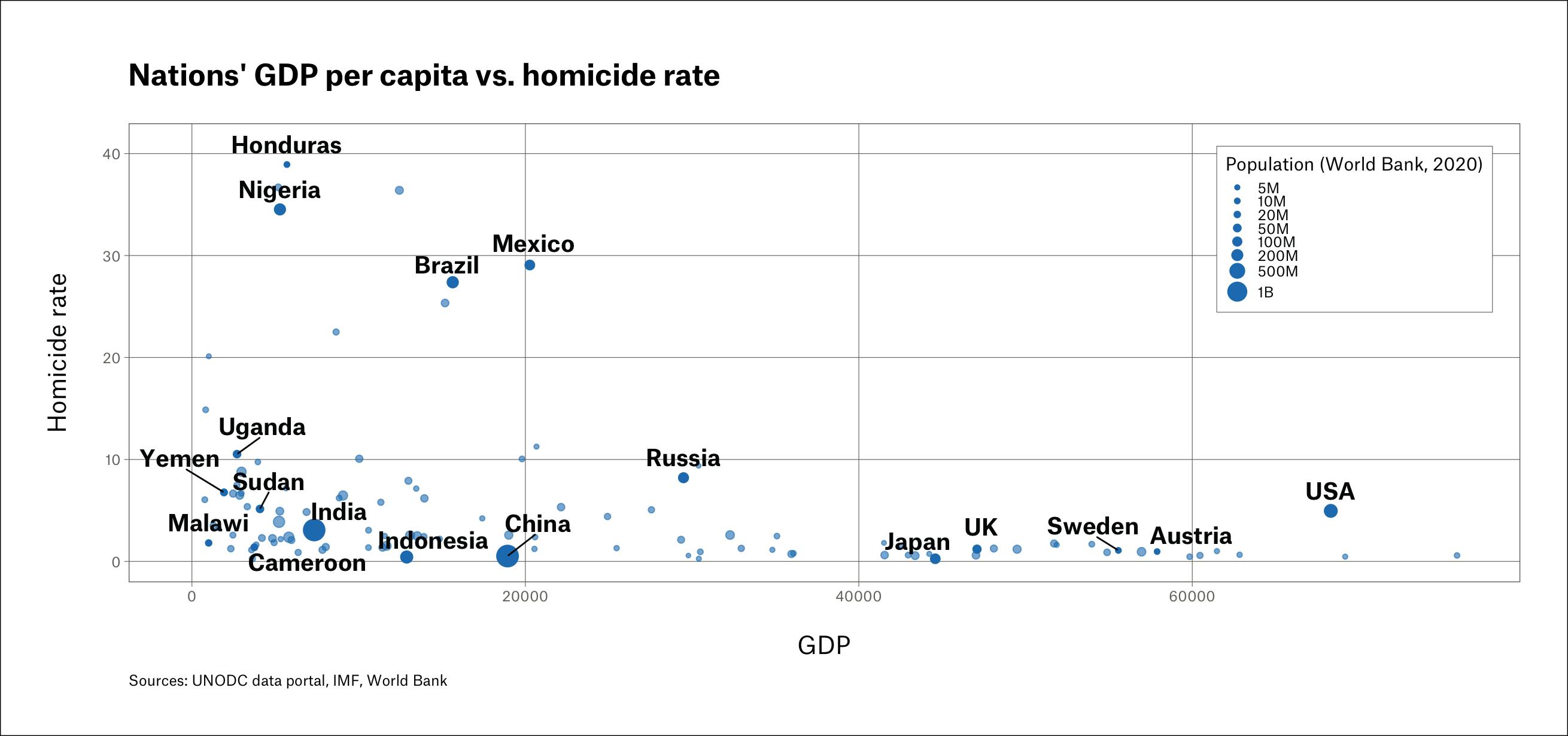

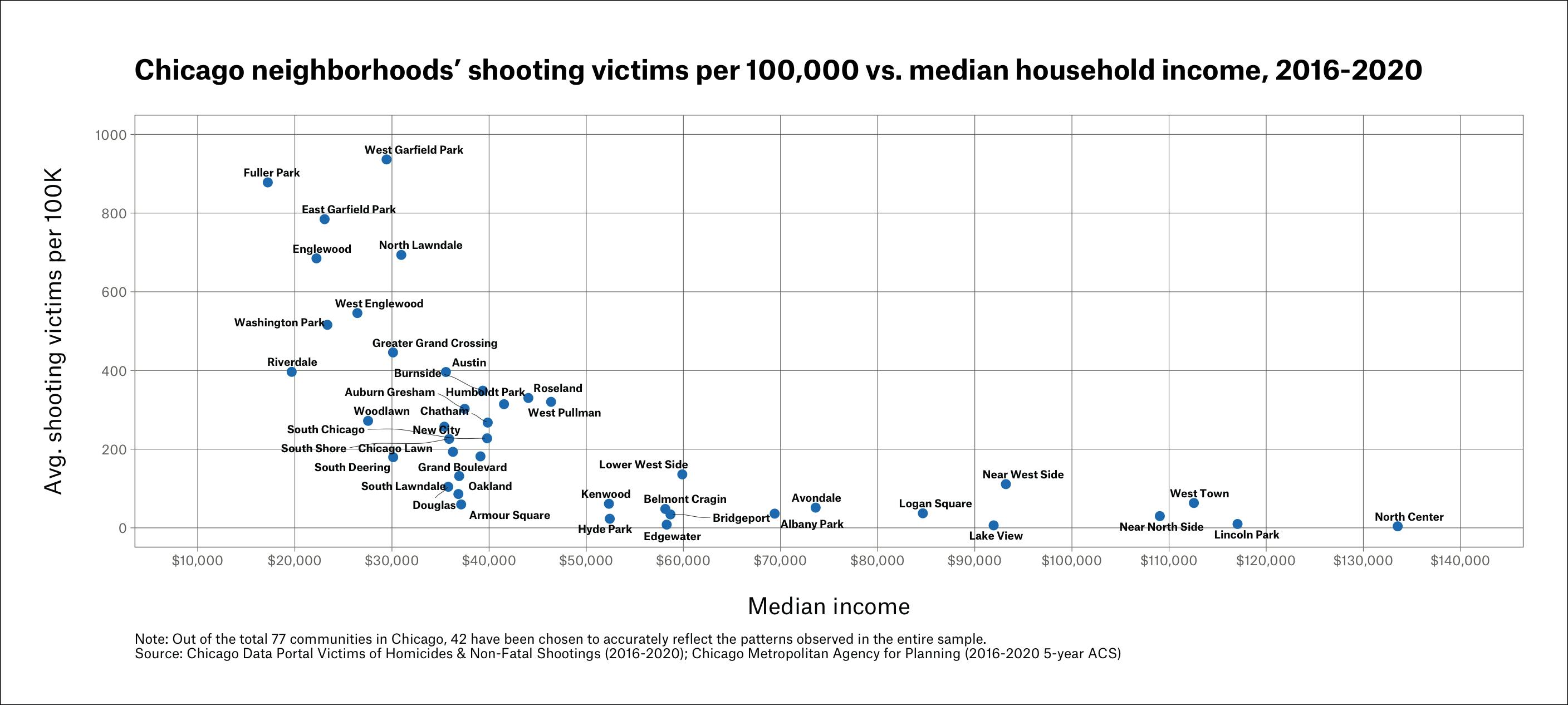

Another way to see the point is to look at shooting rates per capita across neighborhoods in Chicago: While every affluent area is safe, among poor areas there is enormous variability in public safety (Figure 1). We see the same thing looking across countries (Figure 2).

Shooting victims per 100,000 neighborhood residents for a subsample of Chicago’s 77 community areas (“neighborhoods”), related to each community area’s median household income (we show a subsample of 42 of the 77 to improve legibility of the figure)

Homicide rates per 100,000 residents for selected countries plotted against Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita (adjusted for purchase power parity)

One of the most important criminologists of the first half of the 20th century was Edwin Sutherland, who noticed that while there’s more crime in poor neighborhoods than in rich ones, when economic conditions improved in a neighborhood, crime didn’t decline. Sutherland concluded: “Poverty as such is not an important cause of crime.” With the benefit of decades of more data and improved statistical methods, we would amend Sutherland’s conclusion slightly: Poverty as such does not seem to be an important cause of violent crime. In sum, the best available data and evidence suggest that it does not seem to be true that “nothing stops a bullet like a job.”

How do we make sense of these surprising findings? One reason so many people may believe economic conditions affect violence is because they believe violence, like property crime, is also motivated by income. It certainly seems true that the media disproportionately covers or represents the types of murders that are motivated by income, like those related to drug selling or alcohol bootlegging. The most popular or celebrated movies and TV shows include “The Public Enemy,” “The Untouchables,” “The Godfather,” “The Sopranos,” “Scarface” and “The Wire.”

But most violent crimes in America are not obviously motivated by income. We can see in the data that something like 80% of all violent crimes in America are assaults — arguments that escalate into fights. Something like 70-80% of homicides are arguments that escalate into fights and end in tragedy because there’s a gun. Most murders start with words.

Policies designed to alleviate material hardship, as important as those are for improving people’s well-being, don’t appear to be sufficient by themselves to prevent altercations from starting or escalating. We see this in the fact that when aggregate economic conditions change in response to business cycles or local economic development, there is little change in aggregate violent crime rates. That’s consistent with the idea that most measured violence is not driven by teens, people with mental illness, people experiencing homelessness, or victims of domestic violence.

In his wonderful book “The Better Angels of Our Nature,” Harvard psychology professor Steven Pinker decried the “dubious belief about violence…that lower [social] class people engage in it because they are financially needy (for example, stealing food to feed their children) or because they are expressing rage against society. The violence of a lower-class man may indeed express rage, but it is aimed not at society but at the asshole who scraped his car and dissed him in front of a crowd.”

Most murders start with words.

What might those additional efforts be? Behavioral economics gives us a clue.

For starters, it’s useful to make explicit the implicit assumption behind the idea that “nothing stops a bullet like a job.” The notion is that for low-income people, the benefits of crime loom relatively larger (an economist would say there’s diminishing marginal utility of income — stealing $200 is much more meaningful to someone making $20,000 a year than $200,000 a year). And for low-income people with meager earnings prospects, they might feel like they’ve got relatively little to lose from the risks of crime (an economist would say there’s more limited opportunity cost to crime). Crime, in this view, is largely a problem of incentives.

That is, the implicit assumption is that crime is the result of rational, premeditated benefit-cost calculation, the result of the sort of deliberate, conscious thinking that Daniel Kahneman called “System 2” cognition. This makes sense given the seriousness of violent behavior: the risk of injury, extended trauma or even death to another person; the risk to the perpetrator themselves of losing their freedom and spending extended time in jail or prison.

But let’s return to the person in Pinker’s example from above, who escalates to violence after someone scrapes their car and insults them in front of others. What rational incentive is that person responding to? Do we really believe this person has engaged in some deliberate, conscious System 2 benefit-cost calculation and thinks beating someone up is a rational solution to this situation? No. They’re beating the other person up because they’re pissed.

What could that pissed car owner possibly be thinking?

Remarkably, given the high stakes involved, the pissed car owner is probably not “thinking” at all, at least not thinking the way we usually define the term. Because rational, deliberate System 2 thought takes mental effort, our minds often rely on a set of automatic responses we develop to deal with routine, low-stakes situations we see over and over — what Kahneman called “System 1” cognition. System 1 is designed to help us form as simple and coherent a picture of what’s going on, as quickly and effortlessly as possible — all done below the level of consciousness. We’re not even aware of it.

What might the System 1 of Pinker’s car owner have done in that example? System 1 helps us enormously in our daily lives by quickly diagnosing what sort of situation we’re in. Child in need of help. Upset spouse. Elated friend who’s just gotten good news. Extra heavy traffic that suggests something unusual has happened so an alternative route is needed. In the case of the car owner whose vehicle was scraped, it’s not hard to imagine System 1 diagnosing the situation as: “I’m dealing with an asshole.”

How do you treat a human being? With dignity and respect. How do you treat an asshole? All bets are off.

That feature of System 1 which allows us to quickly assess what’s happening, without our even having to consciously think about it, which is normally so useful to us, can sometimes lead to trouble in out-of-the-ordinary or high-stakes situations — like those involving interpersonal conflict. For example, in this case, System 1, designed to create a quick, coherent picture of things, can sometimes confuse a thing’s name for the essence of the thing itself. One study put subjects in front of two containers of sugar, handed the subjects a label that read “sodium cyanide,” asked the subjects to choose which of the two sugar containers they wanted to put the label on, and then asked if they’d be willing to eat the sugar from that container. A remarkably large share of people said “No way.” Once a name has been placed on the container, it’s hard for System 1 to believe the thing itself isn’t that name.

Similarly, once the car scraper has been called an asshole by the car owner, the scraper is no longer a person; they’ve become the name the owner has called them. Without the car owner even realizing it, they’ve dehumanized the other person. How do you treat a human being? With dignity and respect. How do you treat an asshole? All bets are off.

This helps us see why trying to change the incentives for violence so often doesn’t help; it’s targeting System 2, yet so much of violence seems to be driven by System 1 instead. Making the Earned Income Tax Credit more generous, or extending the child tax credit, won’t make the car owner any less pissed in that moment.

More helpful for preventing violence are policies that directly focus on System 1. For example, the behavioral economics perspective implies there can be enormous value in policies that increase the chances someone is around —–- some “‘eyes on the street,”’ as Jane Jacobs famously put it —– to interrupt conflict before it escalates into violence. There’s evidence for that from studies of bolstering local retail, improving street lighting and, cleaning up blighted areas. That’s what a lot of community violence intervention programs try to do with ‘violence interrupters.’ Other programs like Becoming a Man, Choose 2 Change and READI seem to be able to help teach people to self-interrupt the cycle of escalation and violence in difficult situations.

To substantially improve the material conditions of low-income people in the U.S., there is surely value in considering a wide range of jobs and social programs. But to keep low-income communities safe from the part of the crime problem they themselves worry about the most — violence — those policies by themselves won’t be enough. Additional efforts that are explicitly aligned with what violence is and what drives it will be required.

This piece is a distillation of a longer essay, “Does nothing stop a bullet like a job? The effects of income on crime” forthcoming in the Annual Review of Criminology.