One bold move could produce nearly 200,000 units.

The good news is that state and city officials are seriously discussing ways to solve New York City’s housing crisis. A quick swim in the pool of statistics will reveal its severity. In 2021, more than half of the city’s renters — nearly one million households — were rent burdened, in that they paid more than 30% of their incomes toward rent; one-third were severely rent burdened, paying more than half of their income for rent. Only 30% of New Yorkers earn enough to have a “living wage” — the minimum amount to pay for food, clothing, housing, health care, child care, transportation and taxes.

Gov. Kathy Hochul has laid out an agenda, branded the New York Housing Compact, to produce 800,000 new units statewide within the next decade, and Mayor Eric Adams has recently called for the Big Apple to strive for 500,000 units. Hochul’s proposal relies on a combination of rezonings, tax breaks and Albany-imposed consequences when locals fail to draw forth new construction. One area of focus is on transit-oriented development, where housing requirements are greater within walking distance of subway or train stops.

These are ambitious and laudable goals. But to put this in historical context, the last time Gotham completed more than 500,000 units in a decade was the 10-year period ending in 1934. The last time it hit 300,000 units was 52 years ago, with 12% of those in newly-built public housing projects. In the last decade, the city has added only 185,000 units.

The Roadblocks

It’s one thing to have lofty goals — and even blueprints to get there — but it’s quite another to hit these targets. Arguably, we are in this crisis because of the many roadblocks still littering our path.

First is the “self-inflicted” part, which includes restrictive zoning, rent stabilization and lengthy delays for project approvals. For example, there are 2 million housing units outside of Manhattan within one kilometer (0.62 miles) of a subway stop. Yet astonishingly, nearly two-thirds of them are required — by law — to be one or two-family homes.

Today, there is an extensive social and political infrastructure to prevent new construction, either through gumming up reforms in the courts or by having local representatives block new laws and regulations.

And even if we could magically usher in an era of generous upzonings, there is still the issue of rent stabilization regulations. The law currently prohibits tenants from being evicted. Emptying a building for redevelopment can take many years, if ever. Few tenants want to leave when neighborhood vacancy rates are so low, but they are so low because few tenants are willing to leave. You cannot redevelop communities without a plan to relocate people.

More broadly is the general unwillingness of residents to allow wholescale redevelopment in their neighborhoods. There is an extensive social and political infrastructure to prevent new construction, either through gumming up reforms in the courts or by having local representatives block new laws and regulations. At this very moment, opponents are sharpening their knives.

New York could hit its targets if there were a “perfect storm” of public support and policy derring-do, but if history is any guide, it’s hard to be optimistic.

Expanding Manhattan

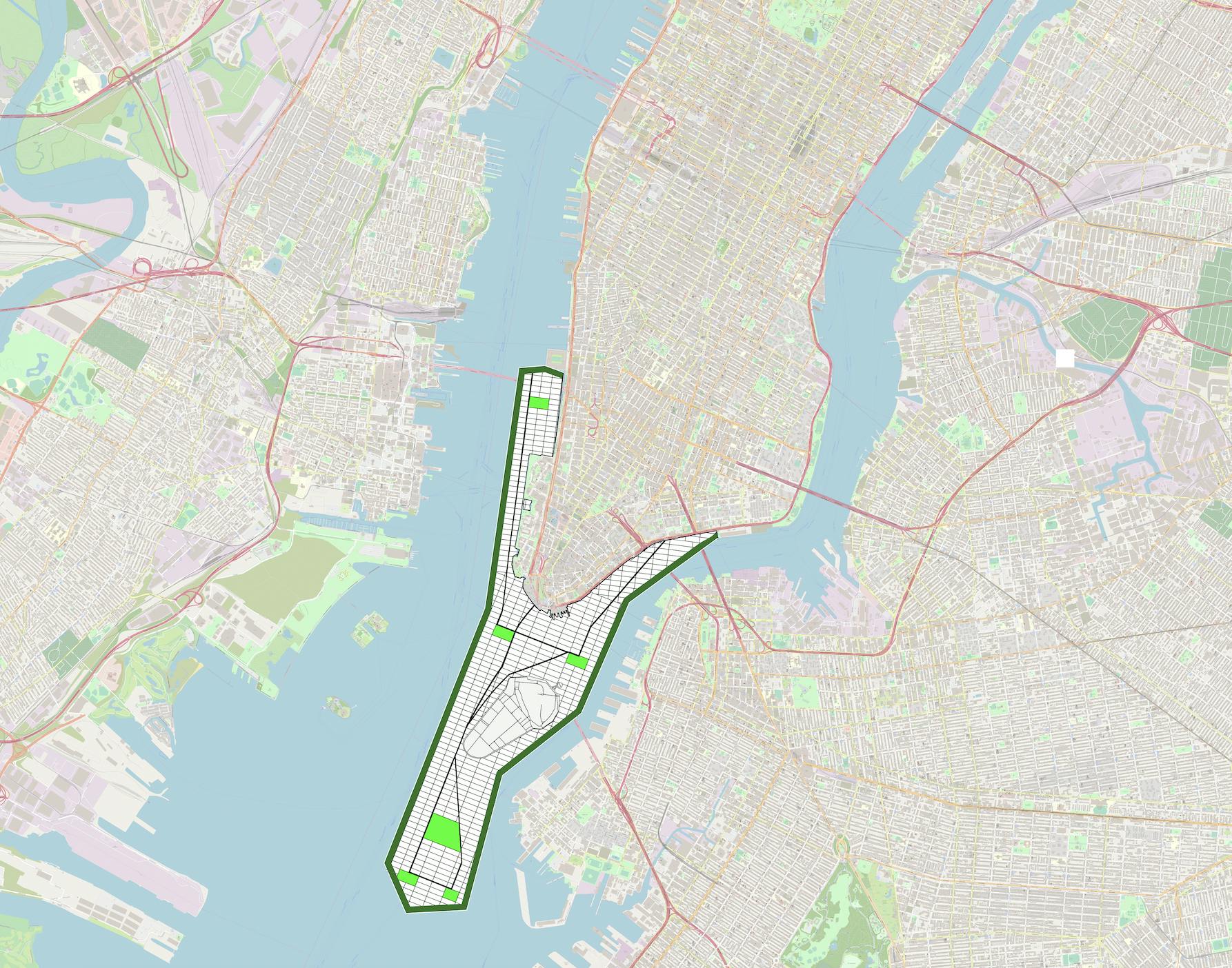

To this end, there is one strategy that can help — by sidestepping some of the fights that drag down the most ambitious political plans to produce more units. In January 2022, I proposed expanding the island of Manhattan 1760 acres into New York harbor.

Expanding Manhattan could produce 180,000 new homes — an unthinkable number to generate in one fell swoop.

This Manhattan extension would provide two benefits. The first is to help build resiliency against rising sea levels and storm surges, an issue that is top-of-mind for many New Yorkers. The new land would protect downtown, still the heart of New York’s economy. It would be constructed at a higher elevation and with wetlands, beaches and berms around its perimeter to absorb surges. Superstorm Sandy in 2012 and Hurricane Ida in 2021 demonstrated how devastating surges and flooding can be, and yet there’s been little action to make New York resilient.

Just as importantly, it would also produce 180,000 new homes — an unthinkable number to generate in one fell swoop — thus working in parallel with Hochul’s and Adams’ plans. Going forward, it’s important to recognize that sea level rise and flooding will be driving decreases in the housing stock along the coast. The housing buyout program on Staten Island, for example, is shrinking communities. We need ways to protect the housing we have.

To many, my proposal is radical. But the idea taps into New York’s long history of creating new land to meet the economic challenges of the day. Lower Manhattan south of City Hall, for example, has been expanded by nearly 50% since the Dutch first created New Amsterdam in 1626. In fact, Battery Park City, built out in the 1970s with excavated material from the World Trade Center site, was largely spared from Hurricane Sandy’s storm surge.

Since the Manhattan extension would be created in the harbor, no tenants would be displaced.

Other cities around the world are constantly creating new land to help them grow. Take the case of Hong Kong. Because it is filled with steep mountains and hills, it has relied on land creation to expand its housing stock. Today about 6% of Hong Kong is on made land, while 25% of its developed land is reclaimed, holding 27% of its population. Hong Kong is currently undertaking an ambitious 2471-acre reclamation project that will provide 260,000 new housing units. Hong Kong is not alone. Singapore and Macau have been even more aggressive in building out into the sea. Over the years, Singapore’s land area has expanded by 24% (34,100 acres), while Macau has grown by 160% (4,695 acres).

Since the Manhattan extension would be created in the harbor, no tenants would be displaced. If planned and executed judiciously, it could generate a net profit for the city coffers. While the costs would be high, likely around $35-50 billion, the benefits could be even greater. Since the value of Manhattan real estate runs so much higher than the cost of creating buildings, the city could use this differential to fund the creation of artificial land and associated infrastructure. Such a project would likely take two decades to complete, and thus should be seen as a complement to other housing policies, rather than as a substitute.

To those who say it will harm the environment and the harbor ecology, I have two responses. First, the region is constantly engaging in sea-based construction. New York is planning to build $52 billion sea walls in the estuary, and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey is perennially dredging the port to improve shipping channels. To summarily reject the Manhattan extension because we can’t touch the harbor is to ignore reality. Secondly, the original “Mannahatta” ecology was rich with wetlands and wildlife. In my plan, we can actually recreate lost wetlands and plant native trees and flowers, potentially increasing biodiversity.

Since New York is finally talking seriously about solving its housing affordability problem, we should put on the table not just rezonings and tax breaks but also other big ideas that can not only add needed housing but can also protect the city in other ways. We have the opportunity to make it more resilient against climate change and produce new vibrant neighborhoods that help Gotham remain a great and dynamic metropolis.