Gun violence, and the fear of gun violence, distort the lives of millions of Americans.

In 2020, there were 375,800 fewer serious crimes in America compared to 2019, about a 5 percent decline. Amidst the overall decline, one specific type of crime ran counter to trend: murders, most of which are committed with guns, were up by 5,000, a rise of nearly 30 percent.

How should we think about these statistics? Should we be happy that serious crime is down or concerned about the increase in homicides? We argue this trend is actually bad news overall. As Berkeley criminologists Franklin Zimring and Gordon Hawkins have noted, crime is not the problem—gun violence is. This distinction has a number of implications for how we think about criminal justice.

Our logic might be easiest to see through analogy. The United States in 2020 also saw a decline in the total number of respiratory viral infections, driven by a massive reduction in the seasonal flu. But amidst this overall decline, there was an increase in one new, specific kind of respiratory virus you have probably heard of: COVID-19. The result is that amidst a large decline in illness, the number of deaths from respiratory viral infections increased from the normal level (30–60,000) to over 600,000.

What’s immediately obvious from this analogy is that every virus is not the same. The public health consequences of the seasonal flu versus COVID-19 are vastly different. Because COVID-19 is so much deadlier than the seasonal flu, billions of people around the world fundamentally changed how they lived their lives. Online replaced in-person, with devastating effects on social life and the economy. A whole generation of schoolchildren were unable to make normal progress in their studies, or in learning how to get along with their peers. The elderly lost contact with their children and grandchildren. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-sponsored survey in the summer of 2020 found that 40 percent of American adults were struggling with their mental health during the pandemic. Among people ages 18–25, the figure was more like 70 percent; fully 1 in 4 young people said that they had considered suicide. Meanwhile, as a direct result of our behavioral responses to COVID-19, the global economy was devastated. In the United States, the unemployment rate of 3.7 percent in 2019 surged to 8.9 percent in 2020.

As with COVID-19, so with crime. Property crime accounts for something like 80 percent of all crime in America. For the victims of a pickpocket or a break-in, crime is a major irritant. For retailers, protecting and insuring against shoplifting and employee theft is a real cost of doing business. But property crimes are rarely life-changing events for the victims. And while the threat of property loss might lead us to take extra care to lock our cars, or install an alarm system, it doesn’t substantially impair the quality of our lives.

In contrast, the fear of gun violence substantially distorts the way that millions of people live their lives. There is increasing evidence that children who witness gun violence tend to underperform in school and have a variety of psychological problems that interfere with normal development. In response to gun violence, families that can afford to move often do. One estimate by economists Julie Berry Cullen and Steve Levitt suggests that, on average, a neighborhood murder has 70 times the effect of other crimes in persuading households to relocate. A high-violence neighborhood suffers reduced property values and business investment. Employers and people of means seek more attractive places to locate. Reduced tax revenues make it harder for the surrounding city to address these challenges. It is easy to see the linkage here between endemic violence and poverty.

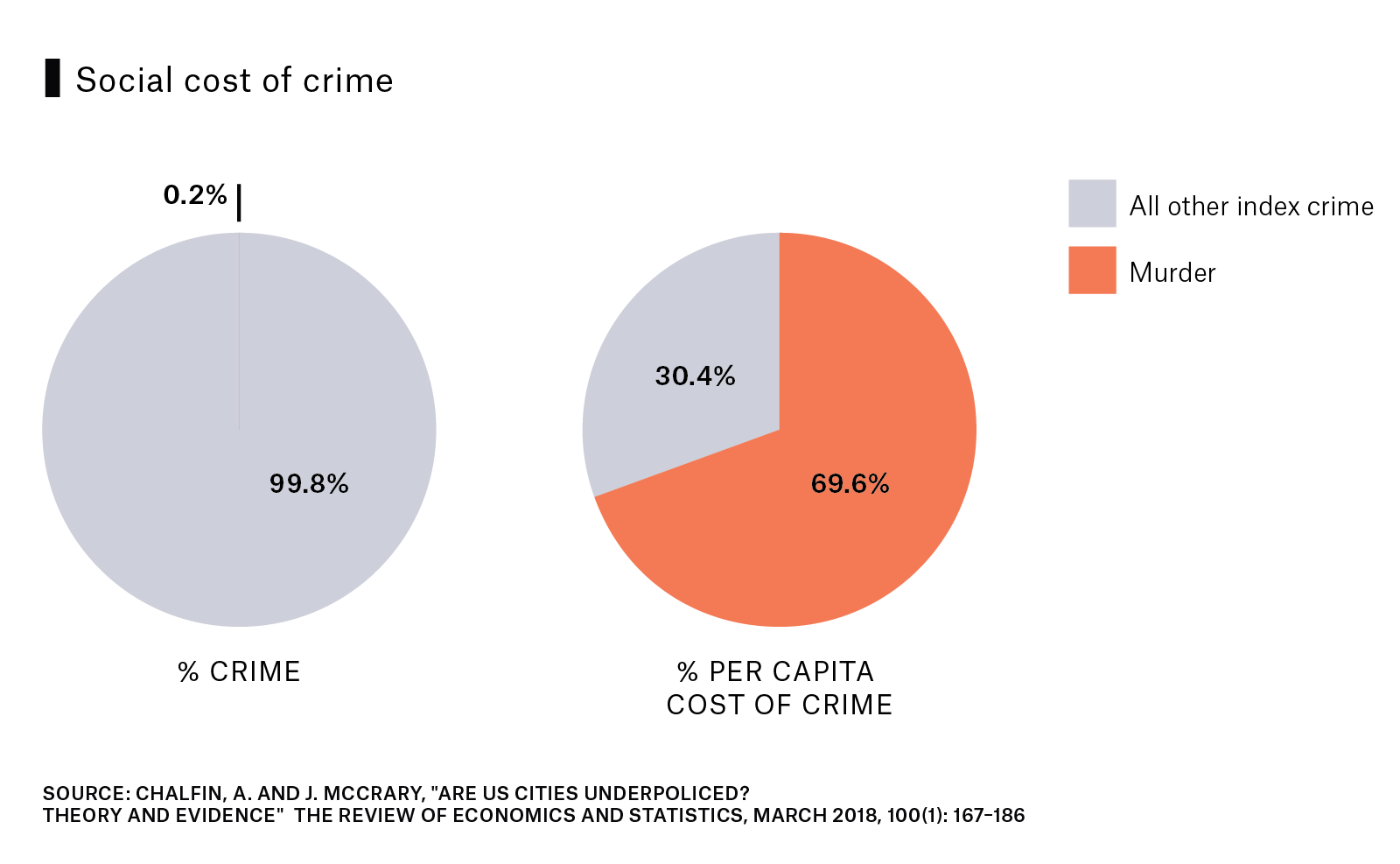

Crime overall may have declined by about 5 percent in 2020, but the social harm from the rise in murders, most of which were committed with guns, more than offset the reduction of several hundred thousand fewer reported crimes total.

The Nobel-laureate economist Thomas Schelling came up with a way to measure the total social harms from different social problems—what people would be willing to pay to avoid or have less of them. A reduction in serious violence would have tangible effects on property values and the cost of the myriad activities to avoid and mitigate victimization, such as long commutes to the suburbs. “Contingent valuation” studies, where a cross section of the public is asked how much they would be willing to pay for reductions in different types of crimes, provide further evidence. One study of this sort by Mark Cohen of Vanderbilt and colleagues estimated the public’s willingness to pay for each prevented crime equaled: $5,098 for larceny, $21,666 per stolen car, $44,606 per burglary, $108,329 per aggravated assault, $369,593 per rape, $356,849 per armed robbery and fully $15.04 million per murder. Crime overall may have declined by about 5 percent in 2020, but the social harm from the rise in murders, most of which were committed with guns, more than offsets the reduction of several hundred thousand fewer reported crimes total. The result is that, on net, the total costs or harms of crime in America (murders plus all other crimes) increased by $72 billion according to the willingness-to-pay framework.

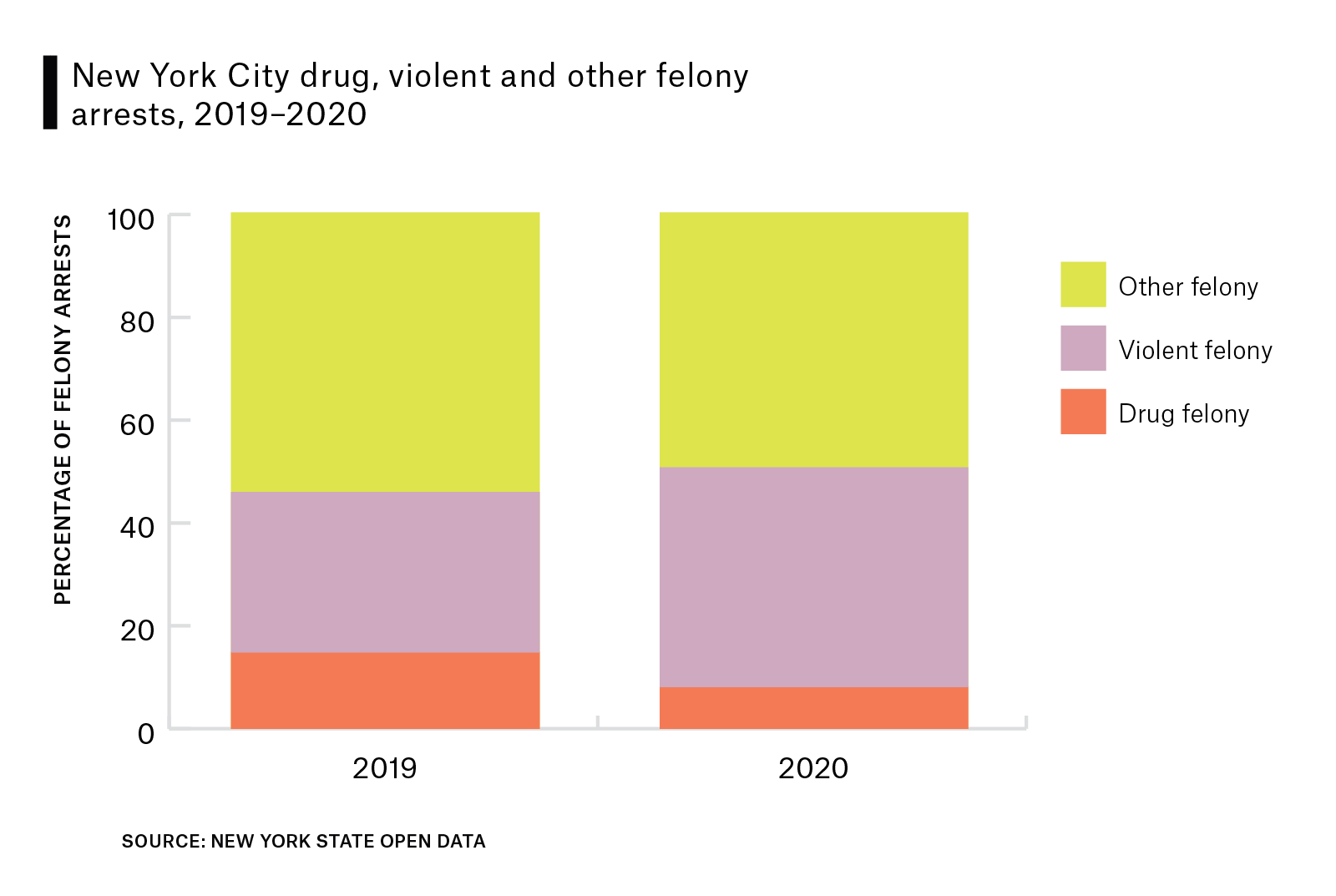

If the problem of crime in America is indeed first and foremost a problem of gun violence, several important implications follow. The first is to ensure that law enforcement agencies prioritize violence prevention. “Public safety” begins with protection against fear, injury, and death. Further, the victims of gun violence, most of whom are from low-income minority households, need help of all kinds. They also need to believe that their cases are being taken seriously. Ensuring accountability for gun violence can improve public safety without exacerbating the problem of mass incarceration; murders account for only about one-tenth of one percent of all arrests. In a country where the share of unsolved murders increased from 1-in-20 in 1965 to 1-in-3 today (and is more like 1-in-2 in cities like Chicago), law enforcement in America for some reason made 1.5 million arrests for drug charges in 2019—the vast majority of which, research suggests, have very little public safety value.

We must account for the consequences on crime, especially violent crime, when we are thinking about how much to invest in social policies. New York’s summer jobs program for teens is a case in point; knowing that this program not only provides valuable income and work experience to young people, but also reduces homicide, is surely relevant for decisions about how widely to scale those efforts. Another example is the effort to clean up vacant lots in Philadelphia, which might initially be thought of as a “nice to have” in a city struggling with so many other big problems—until we see in the data that such beautification efforts reduce gun violence. While some criminologists have disputed large estimates for the social costs of gun violence on political grounds, fearing that they may be used to justify policies they don’t like (such as imprisonment), the large burden gun violence imposes on society is equally an argument for more spending on social programs.

The direct victims of gun violence tend to come from a fairly narrow slice of society, but the threat of gun violence has far-reaching implications. It is serious violence that does the most damage to our quality of life. We recall the “crack” era a generation ago and shudder. As gunplay once again becomes common in formerly peaceful neighborhoods, peace of mind is among the victims. ◘

Thanks to Elizabeth Rasich for valuable assistance.

Further Reading

Philip J. Cook and Jens Ludwig, Gun Violence: The Real Costs, (Oxford University Press, 2000).

Alexander Gelber, Adam Isen, and Judd B. Kessler, “The effects of youth employment: Evidence from New York City Lotteries,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, (2016), 423-460.

Bernard E. Harcourt and Jens Ludwig, "Reefer madness: Broken windows policing and misdemeanor marijuana arrests in New York City, 1989-2000," Criminology & Pub. Pol'y 6 (2007): 165.

Patrick Sharkey, “The long reach of violence: A broader perspective on data, theory, and evidence on the prevalence and consequences of exposure to violence,” Annual Review of Criminology, 1 (2018): 85-102.

Franklin E. Zimring and Gordon Hawkins, Crime Is Not the Problem: Lethal Violence In America, (Oxford University Press, 1999).