How New York’s hottest months are depicted, and distorted, on film

The first images that splash across the screen are the most familiar of urban cinema: New York City at daybreak. The lights have not yet dimmed on the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges; the sun is just beginning to peek through and bounce off the skyscrapers of the Manhattan skyline; the first ferry of the morning is cruising across the Hudson. But there’s something off about these compositions, which are less iconic than disquieting. That sun is blasting, casting a sickly orange hue that makes the city look less like the Big Apple than the Big Carrot. The lyrics of the accompanying song, by The Lovin’ Spoonful, put a finer point on it:

Hot town, summer in the city

Back of my neck gettin’ dirty and gritty

Been down, isn’t it a pity?

Doesn’t seem to be a shadow in the city

All around, people lookin’ half dead

Walkin’ on the sidewalk, hotter than a match head

And then we’re at street level, downtown Gotham, the sounds of the Spoonful augmented by the noise of the city — blasting horns, passing cars, shouting cabbies — and the sights of a city’s day, well underway — street vendors, commuters exiting the subway, curb-to-curb traffic, shop owners hosing off their patch of sidewalk.

And then, mid-lyric, a bomb explodes inside Bonwit Teller, and “Die Hard with a Vengeance” is off and running.

Set your movie in a sweaty New York summer, and half your work is done; countless filmmakers before you have established these months as a time when anxieties run as high as temperatures.

Upon close examination, the plot of this 1995 action extravaganza, the second sequel to the oft-imitated 1988 hit “Die Hard,” does not require a summer setting. (The debate rages annually as to whether the original is a Christmas movie; perhaps the real controversy is whether “Vengeance” is a summer movie.) But there’s just something about New York City in the summer that draws filmmakers to tell their stories of crime, chaos and rot in our borders within those months, something about the match-hot sidewalks and half-dead-looking citizenry that sets an immediate, palpable and even uncomfortable mood. It’s part of the city’s DNA: an abundance of pre-war (and thus pre-central-air-conditioned) buildings, a covering of cement reflecting and increasing the sun-blasted heat and the inevitable flaring of tempers as the city’s overcrowded numbers push up against the inflexible confines of subway cars, buses and the borders of the island itself.

One could even say it’s a matter of shorthand. Set your movie in a sweaty New York summer, and half your work is done; countless filmmakers before you have established these months as a time when anxieties run as high as temperatures. When director John McTiernan opened “Die Hard with a Vengeance” with those off-the-cuff images of the city beginning its day, he wasn’t just setting a scene; he was also paying homage. In 1975, one of the greatest of all New York filmmakers, Sidney Lumet, opened his “Dog Day Afternoon” in the exact same way.

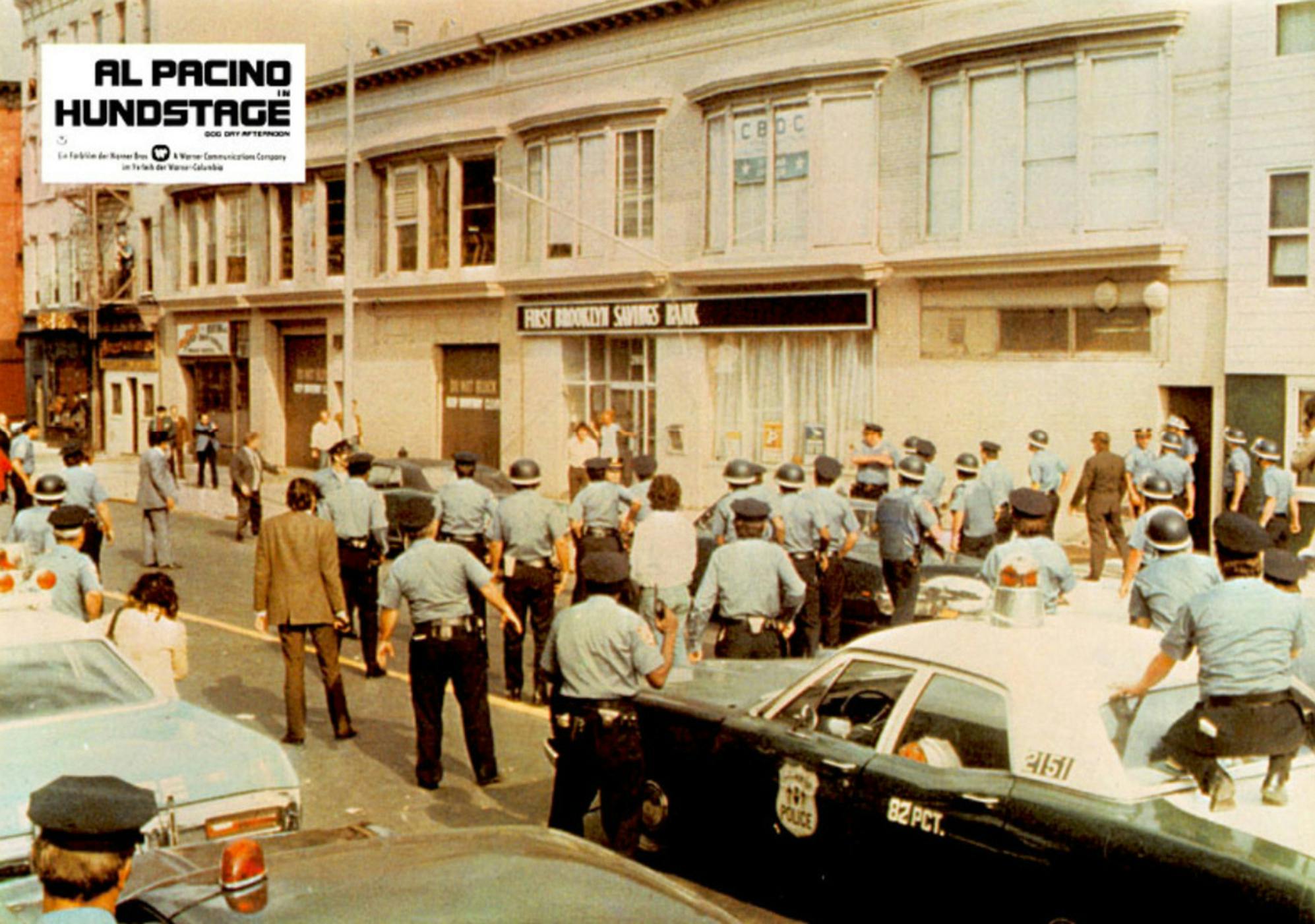

Lumet wasn’t merely scene-setting in the summer for the sake of atmosphere. He starts his film with an explainer: “What you are about to see is true — It happened in Brooklyn, New York on August 22, 1972.” On that hot day, 27-year-old John Wojtowicz attempted a bank robbery that turned into a 14-hour hostage situation (and media sensation). So, as McTiernan would 20 years later, Lumet opens with a song (this time, Elton John’s “Amoreena”) and images of city life: the Circle Line ferry heading out to the Hudson, shirtless construction workers on the job, a suburban dad watering his lawn, a kid leaping into a rooftop pool, old men on the beach at Coney Island and finally our three bank robbers in their car in front of First Brooklyn Savings Bank — the song revealed as diegetic music, blaring from their car radio.

Lumet had cinematographer Victor J. Kemper drive around and capture these images on the sly, their handheld framing giving away their “stolen” status. But they also lend the film a sense of documentary realism that goes hand-in-hand with his based-on-a-true-story narrative and sets up the desperation of what will follow: These are not all carefully staged images of summertime frolic but candid portraits of poor people, street people, frustrated people. Through “Dog Day Afternoon,” the film’s Wojtowicz avatar, Sonny, played of course by Al Pacino, loses his cool both literally — police turn off the building’s air conditioning as a discomfort tactic — and figuratively. Sweaty, overheated, uncomfortable people are often not thinking with a clear head, it seems.

The following year, another classic of Rotten Apple cinema made this point even more clearly. Martin Scorsese shot “Taxi Driver” in the summer of 1975 and captured a city on the brink — teetering perilously close to bankruptcy (the notorious “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD” headline would appear the following fall), while police protested potential layoffs with fearmongering flyers. Ten thousand sanitation workers were on strike, leaving an estimated 58,000 tons of garbage to sit on the streets and sidewalks. Residents started setting them on fire, but since budget cuts had closed several fire stations, they were left to burn, turning parts of the city into “a vast incinerator of flaming garbage.”

Scorsese found himself directing his crew to move garbage out of shots, lest he be accused of making the city look too bombed-out for his portrait of a Vietnam vet turning the corner into madness and violence.

But there’s just something about New York City in the summer that draws filmmakers to tell their stories of crime, chaos and rot in our borders within those months.

“It was all there,” Scorsese told me, “and that’s what you see in the movie. I mean, you could taste it in the air. There was a sense of desperation. There was a sense of violence in the air too. But hot summers ... with the heat, everybody’s outside, they have no air conditioning, getting on each other’s nerves. The whole city was like that.” “Taxi Driver” was already the story of a man simmering to a boil; in this particular New York summer, it was not a question of “if” but “when.”

Even films that weren’t shot under such duress benefited from common knowledge and conventional wisdom of what people might do under the pressure and discomfort of summer in the city. The little-seen but masterfully executed 1949 film noir “The Window” bakes the circumstances of summer city living right into its premise, when a Lowest East Side slum kid (Bobby Driscoll) goes to sleep on his fire escape on a hot summer night — as many did in that period — and accidentally peeks in on his neighbors murdering a drunken sailor. The picture was based on a 1947 Cornell Woolrich story called “The Boy Who Cried Murder.” A few years later, Alfred Hitchcock adapted a similar Woolrich story called “It Had to Be Murder” into his seminal exploration of voyeurism, impotence and summer sweat, “Rear Window.”

Hitchcock wasn’t shooting in the streets of New York — quite the opposite, in fact, as he built an elaborate set for the film’s Greenwich Village apartment building on the Paramount lot in Hollywood. But the detailed set (by designers Hal Pereira and Joseph MacMillan Johnson) allowed Hitch to create and replicate the distinctive markers of city heat: open windows, half-clothed neighbors, afternoon cat naps and moistened brows. It’s so blisteringly hot, wheelchair-bound James Stewart becomes convinced Raymond Burr has murdered his wife; Stewart keeps picking fights with Grace Kelly, for goodness’ sake, and if that’s not proof the heat makes you do crazy things, nothing is.

In that heat, what’s real and what’s imagined, what’s rational and what’s paranoid, melt and stick together in Jimmy Stewart’s mind.

One New York City filmmaker in particular understood the role a sweltering summer day can play in jettisoning all sense of moderation.

“It’s been my observation that when the temperature rises beyond a certain point, people lose it,” Spike Lee wrote in his journal on Christmas Day 1987. “Little incidents can spark major conflicts. Bump into someone on the street and you’re liable to get shot. A petty argument between husband and wife can launch a divorce proceeding. The heat makes everything explosive, including the racial climate of the city.”

These musings, of course, resulted in his 1989 film “Do the Right Thing,” which remains the quintessential cinematic dramatization of summer in the city. From its opening sequence — in which the neighborhood disc jockey (Samuel L. Jackson) announces, “I have today’s forecast for you: HOT!” — the picture is suffused with the details of staying cool on the hottest day of the summer: cold showers, cold beers, Italian ices and, of course, opening up the fire hydrant and spraying down your friends (and the occasional passing convertible).

The “johnny pump” sequence underscores one thing that’s notably absent from too many cinematic snapshots of New York in the summer: fun. Our representation is so frequently found in stories of, as Lee put it, people losing it that we don’t often see New Yorkers enjoying themselves on stoops, at pick-up games and in the public pool. The recent (and lovely) “In the Heights” made some strides toward correcting this oversight. Perhaps this is the last, great, unexplored frontier for Gotham moviemakers: unflinching portraits of New Yorkers having a steamy good time in the harsh sunlight of a summer in the city.