A great new book bridges the uncanny valley separating us from the real and imagined New Yorks gone by.

“Site Lines: Lost New York 1954-2022,” Jill Gill - Goff Books, 2024

“Another America,” Images by Phillip Toledano, Text by John Kenney - L’Artiere, 2024

+

“Lost New York,” at the New York Historical Society through Sept. 29

“Wonder City of the World: New York City Travel Posters,” at Poster House through Sept. 8

Amid the postpandemic uncertainty about the future of New York, there are ever-rising waves of nostalgia washing over this city of maybe.

Some of that hindsight is on display at two ongoing exhibitions, “Lost New York” at the New York Historical Society and “Wonder City of the World: New York City Travel Posters” at Poster House.

The “Lost New York” exhibition is a collection of a few dozen often resonant albeit semirandom scraps of the grand city that was before the still grander city that is.

Photographs and paintings show glimpses, mostly of Manhattan, of everything from the grand Bonwit Teller department store to the iron-and-glass Crystal Palace that burned down in what’s now Bryant Park in 1858, from the old Yankee Stadium to Central Park’s Hooverville, along with symbols of 1980s decay from an art collective squatting near Bryant Park, including a broken-hearted update of the iconic “I Heart New York” logo nearly two decades before 9/11.

“Wonder City,” for its part, shows a few dozen 20th century travel posters that convey a city flattened into its iconographic symbols — the Statue of Liberty, the Brooklyn Bridge, the World Trade Center — or fully abstracted into modernist skyscraper shapes and neon colors that aren’t really place-specific, like a preinternet Brooklynization of everything.

Several of the posters are by David Klein, whose midcentury TWA posters, including his almost Kandinsky-esque Times Square, are still immediately recognizable.

Also seemingly recognizable at a glance, and uncanny upon a closer look, are many of the images from a fabricated post-WWII Manhattan in the new book “Another America” — which, despite the name, is highly New York City-specific. Along with brief accompanying texts by New Yorker writer John Kenney, the pictures, generated with artificial intelligence and credited to Philip Toledano, include a city-block sized sinkhole in Manhattan, vaguely evocative of 9/11; the aftermath of a 70-foot wave washing over Manhattan; people looking bored with their heads on fire; bears and wolves watching over the city’s children; and more such weirdness — a veritable virtual Unetaneh Tokef.

As Kenney explains at the beginning of the book, “The arrival of AI is the next stage in the demise of truth. We can recreate the world as it never was … complete with people, events, and disasters,” with images that are “simultaneously familiar and strange, much like the world in which we live.”

Back at the Poster House, there are postcards for sale in the gift shop of images from the show that are immediately familiar and, after a moment’s examination, strange, including a 1968 image by Tomoko Miho where what appear at first to be the windows and texture of Wall Street’s skyscrapers are actually stock-price listings from the business pages.

In New York, the traveler is invited to visit the city and, at the same time, to examine some old postcards that show it as it used to be: the same identical square with a hen in the place of the bus station, a bandstand in the place of the overpass, two young ladies with white parasols in the place of the munitions factory. If the traveler does not wish to disappoint the inhabitants, he must praise the postcard city and prefer it to the present one, though he must be careful to contain his regret at the changes within definite limits; admitting that the magnificence and prosperity of the metropolis New York, when compared to the old, provincial New York, cannot compensate for a certain lost grace, which, however, can be appreciated only now in the old postcards, whereas before, when that provincial New York was before one’s eyes, one saw absolutely nothing graceful and would see it even less today, if New York had remained unchanged; and in any case the metropolis has the added attraction that, through what it has become, one can look back with nostalgia at what it was.

Beware of saying to them that sometimes different cities follow one another on the same site and under the same name, born and dying without knowing one another, without communication among themselves. At times even the names of the inhabitants remain the same, and their voices’ accent, and also the features of the faces; but the gods who live beneath names and above places have gone off without a word and outsiders have settled in their place. It is pointless to ask whether the new ones are better or worse than the old, since there is no connection between them, just as the old post cards do not depict New York as it was, but a different city which, by chance, was called New York, like this one.

That, with the name of the city transposed from Maurilia to New York, is the sketch “Cities and Memory 5” from “Invisible Cities,” Italo Calvino’s 1972 masterpiece, translated by William Weaver, in which Marco Polo briefly describes to Kublai Khan dozens of the cities in his vast empire.

At one point, the emperor asks Polo about his own home city, and the merchant and explorer replies:

“Every time I describe a city I am saying something about Venice.”

If both exhibitions and “Another America” are in some sense backward glances from the present, through a glass darkly, at old and lost antediluvian New Yorks, there is a new work that’s the culmination of a lifetime engaging with the city, a full and focused look at the scenes it preserves from the city’s ever-changing streetscape — the individuality and the muchness of what was here and had been so powerfully present and seemingly permanent it could be hard to take notice of at the time or to recollect afterward.

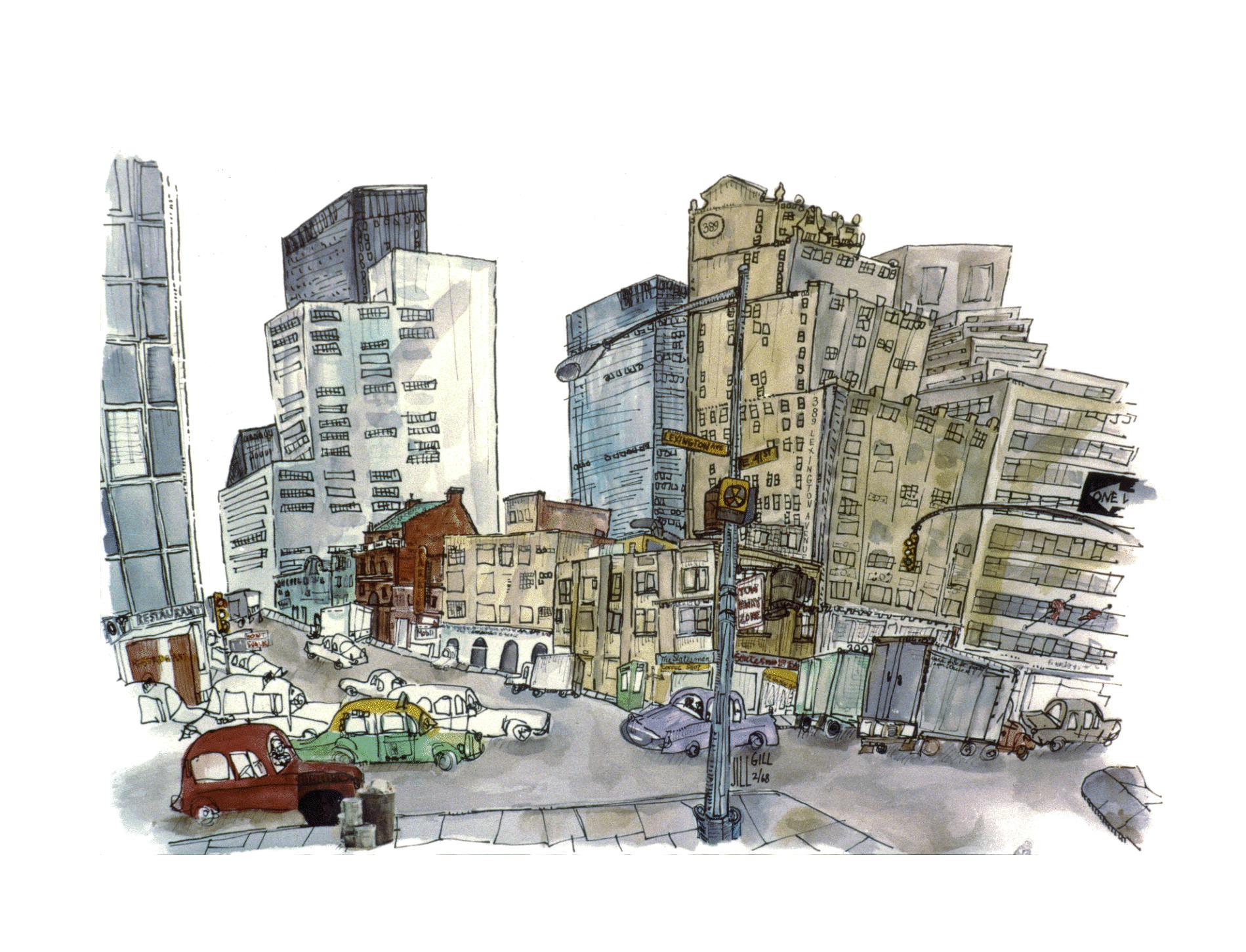

That’s “Site Lines” by Jill Gill, a nonagenarian lifelong Manhattanite. In watercolors and short essays accompanying them, she traverses Manhattan, going north from the 20s on Second and Third Avenues up to 88th Street on the Upper East Side and 95th Street on the Upper West Side, and in time from the mid-1950s to the 2020s.

“Site Lines” may be the best book about New York City so far this century, a richly detailed evocation of what was by a thoughtful narrator and illustrator who’s put in the time. The book doesn’t entirely neglect Manhattan icons but focuses instead on “the haphazard buildings that touched me,” as Gill writes in her introduction. “They were the patches on the fabric of my personal city.”

Gill’s watercolors — a soft medium that turns out to be a striking and surprisingly apt one for showing hard and inorganic city blocks and their pedestrian buildings — gain power through their accumulation, showing block by block the way things were, along with her granular essays about what was once there and how those things felt and what changed and how those changes felt.

In a short and sweet 2020 documentary, “Her New York” directed by David Gross, the artist lays out her approach in somewhat broader strokes.

“It’s my countryside, as it were, and I love — I’m intimate with it. And I get sad when things I love die,” Gill explains. “The more I look at my New York paintings, the more I see things that I just took for granted originally, because that was the world.”

“Site Lines” may be the best book about New York City so far this century.

She recalls in the documentary how in 1954, the year “Site Lines” begins, the Third Avenue El was being torn down in Manhattan: “Suddenly, the sky — there was a sky and it was a wide boulevard where there had just been this massive steel animal.”

Soon, she continued, “It’s as if it had never happened. That’s why I did the paintings of buildings that were going to be thrown away, and making them individual, showing their individuality even though they all are much of a muchness …

“The paintings are also preserving streets that … weren’t very important, except that’s what the neighborhood looked like. People lived in the tenements and there were laundries and pawn shops and barber shops with red-and-white striped poles and a million fruit markets and junk shops, antique shops spilled out onto the street. The streets were much more of a bazaar before they became bizarre behemoths of glass-and-steel office buildings.”

Gill’s images make up much more than a postcard city for travelers to praise, which helps explain why her “Lost New York” hasn’t received the swooning reception, since its publication last December, that’s gone to the likes of Jeremiah Moss and others thirsty to celebrate the supposed greatness of past New Yorks that often preceded the arrival of those writers or their readers.

“Things have to change, and I think some of the changes are absolutely fascinating,” Gill says at the conclusion of “Her New York.” “Even newcomers to the city find in a few years here their local diner or cleaners or whatever has gone out of business. So it’s constant, the change … It’s not a bad thing that they’re not there anymore, as long as you can see what they were and derive your own impressions of what life must have been …

“When I walk down the street anyway, I very often see what was there and what is there. Sometimes I wish they could both exist at the same time, if I like what’s there now, because they do in my mind, and I wish they could exist, but I like what replaced them. So I wouldn’t want that never to have happened.”