Forty years after its initial publication, the broken windows theory is still generating fierce debate.

Few ideas have reverberated as loudly, or for as long, as the broken windows theory.

The enduring influence of broken windows has a lot to do with the power of metaphor. Writing in The Atlantic in 1982, George Kelling and James Q. Wilson sought to explain the importance of police playing a role in maintaining public order. Kelling and Wilson believed that disorder and crime were “inextricably linked.” To help explain this connection, they alighted upon a potent mental image: the broken window.

“One broken window is a signal that no one cares,” they declared. For Kelling and Wilson, broken windows, if left unrepaired, fostered an atmosphere of lawlessness that would eventually lead to more wrongdoing. “Serious street crime flourishes in areas in which disorderly behavior goes unchecked,” they wrote.

Kelling and Wilson’s argument struck a powerful chord for many readers. The New Yorker labeled their article “the Bible of policing.” Indeed, in the years after 1982, broken windows helped to spark significant reform in police departments across the United States. Along with other innovations that were introduced around the same time, including problem-oriented policing, community policing and CompStat, broken windows helped shift the orientation of policing in the United States — from reacting after offending has occurred to aggressively attempting to reduce crime. In particular, the broken windows theory encouraged police to focus more of their time and attention on low-level crimes and visible signs of disorder, including public urination, vandalism, prostitution and public drinking.

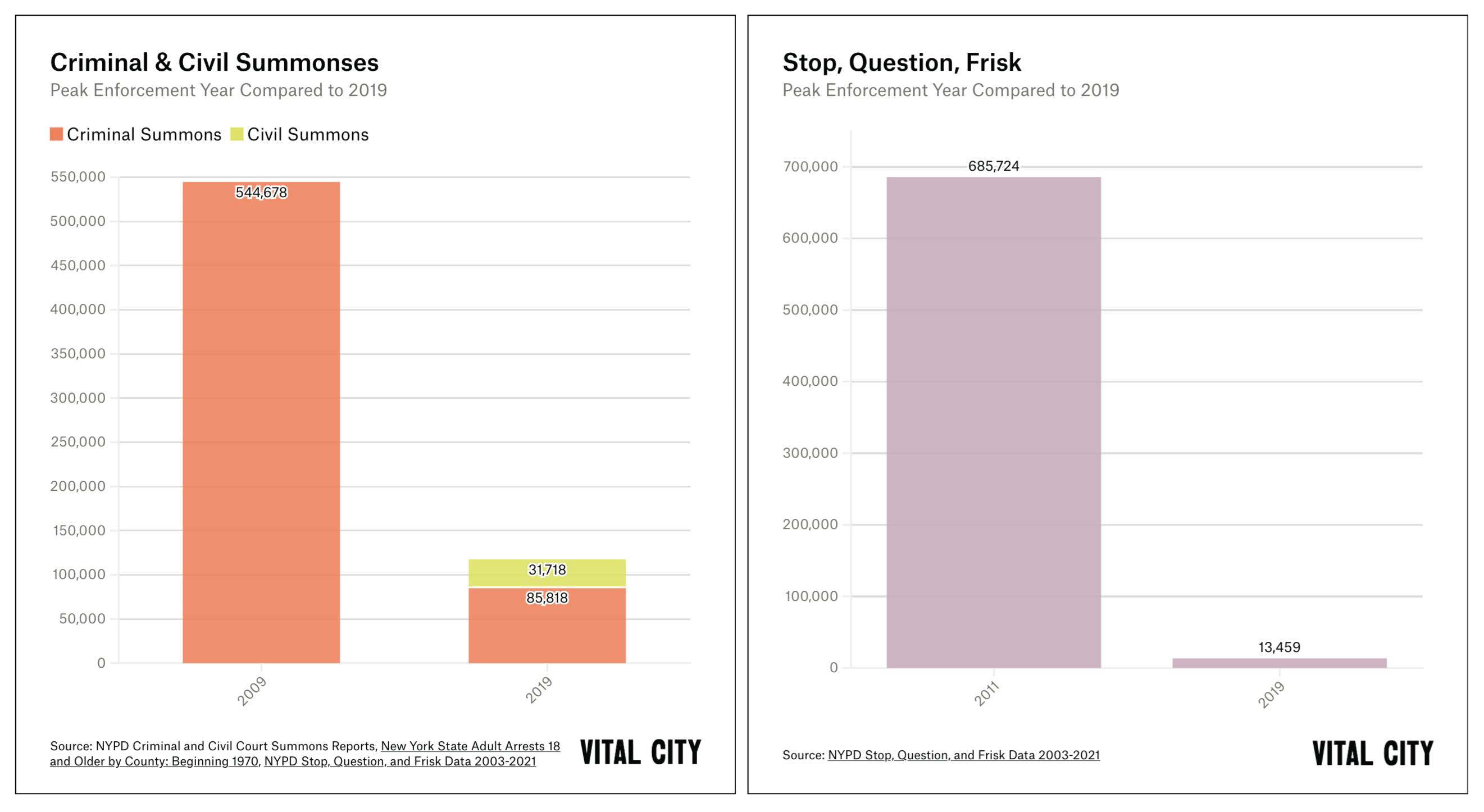

For proponents, broken windows enforcement is an essential crime-fighting tool. Many have credited broken-windows policing with playing a significant role in the “New York miracle” that dramatically reduced crime in the city. While no one can say for certain why crime went down in New York City starting in the 1990s, there is no doubt that, in the decades after the publication of “Broken Windows,” misdemeanor enforcement spiked. In New York City, misdemeanor arrests went up throughout the 1990s and 2000s, peaking in 2010 with slightly less than 229,000 arrests.

But even as prominent police officials like Bill Bratton extol the virtues of broken-windows policing, a significant backlash has been brewing. A number of significant developments have helped bolster opposition:

- The death of Eric Garner, who was killed by a police chokehold in 2014 after being caught selling loose cigarettes in Staten Island.

- The massive expansion of “stop, question and frisk” under Police Commissioner Ray Kelly, which was subsequently found unconstitutional by a federal judge.

- A lawsuit by NYPD whistleblowers, who claimed that an informal arrest quota system targeted Black and Latino New Yorkers.

Along with political and community pushback have come serious questions from academic researchers. “There is no evidence that policing disorder lowers crime or that broken windows works,” Columbia University law professor Bernard Harcourt declared in his 2005 book Illusion of Order: The False Promise of Broken-Windows Policing. In a similar vein, a study in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, found that prosecuting minor offenses does more harm than good. According to the authors, “Scaling back the prosecution of nonviolent misdemeanors leads to an increase, not decrease, in public safety.” On the other hand, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, in a report on proactive policing strategies, concluded that “interventions that use place-based, problem-solving practices to reduce social and physical disorder have reported short-term crime reduction impacts.”

Any fair reading of the literature would suggest that the research on broken-windows policing is inconclusive. A review by the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy at George Mason University came to this decidedly unsexy conclusion: “There is no clear answer as to the link between crime and disorder and whether existing research supports or refutes broken windows theory.”

We have learned the hard way that if the police fail to focus on due process and fair treatment, the consequences can be utterly corrosive to police-community relations.

So where does this leave us? Is there a way out of the seemingly endless debate between those who say that broken-windows policing is a “moral imperative” (City Journal) and those who claim it has led to the “criminalization and over-policing of communities of color and excessive force in otherwise harmless situations” (Campaign Zero)?

Any effort to salvage broken windows must begin by acknowledging the damage that has been done in its name. To their credit, Kelling and Wilson anticipated that broken windows policing was not easily reconciled with due process or fair treatment. In the years since they wrote, we have learned the hard way that if the police fail to focus on due process and fair treatment, the consequences can be utterly corrosive to police-community relations, particularly among Black populations that have long felt that police do not have their best interests at heart.

But even as we jettison practices associated with broken-windows policing (like the widespread use of stop-question-and-frisk) that have been documented to disproportionately harm Black and Latino young people, we should be wary of throwing out the baby with the bathwater. The broken windows theory contains important insights that we ignore at our own peril.

Our safest neighborhoods tend to have almost no visible police presence.

Two kernels of wisdom in particular stand out:

- Perceptions matter — Kelling and Wilson understood that fear of crime is as important as actual criminal behavior. These things are related, of course, but they are not the same. According to Kelling and Wilson, “In Boston public housing projects, the greatest fear was expressed by persons living in the buildings where disorderliness and incivility, not crime, were the greatest.” As Kelling and Wilson make clear, it is not enough to combat crime — we must also combat public fear of crime. Fear erodes community, and without a sense of community, it is almost impossible to summon the kind of informal social control that generates voluntary compliance with the law.

- Policing isn’t the only answer — While broken windows is largely devoted to the work of police, the 1982 article also acknowledges that “many aspects of order maintenance in neighborhoods can probably best be handled in ways that involve the police minimally if at all.” Indeed, our safest neighborhoods tend to have almost no visible police presence. Police are not necessary in these places because there is enough trust among neighbors — and enough eyes on the street — that local residents are able to encourage law-abiding behavior by themselves.

Going forward, cities like New York should seek to build on these insights. This means adopting a three-pronged strategy:

- Improving the physical environment — By cleaning up abandoned lots, enhancing lighting and taking care of public parks, we can help deter criminal behavior.

- Encouraging our neighbors and merchants to keep track of what is happening on the sidewalks and subways — By sponsoring volunteer programs, urban gardening projects and public arts initiatives, we can get local residents out of their apartments and help reclaim public spaces.

- Creating off-ramps out of the conventional justice system — When enforcement is necessary, police, prosecutors and judges should be actively looking for opportunities to divert those apprehended for minor offenses to community service projects and short-term social service interventions in lieu of traditional case processing and conventional sentencing options, like jail.

In sum, we should seek to maintain public order without unnecessarily exposing thousands of New Yorkers to criminal convictions and jail time. By creating effective diversion programs and launching new community clean-up efforts, we can mend broken windows, both in theory and in real life.