Stop lamenting the subways that weren’t, and start understanding the main drivers of New York’s subway history.

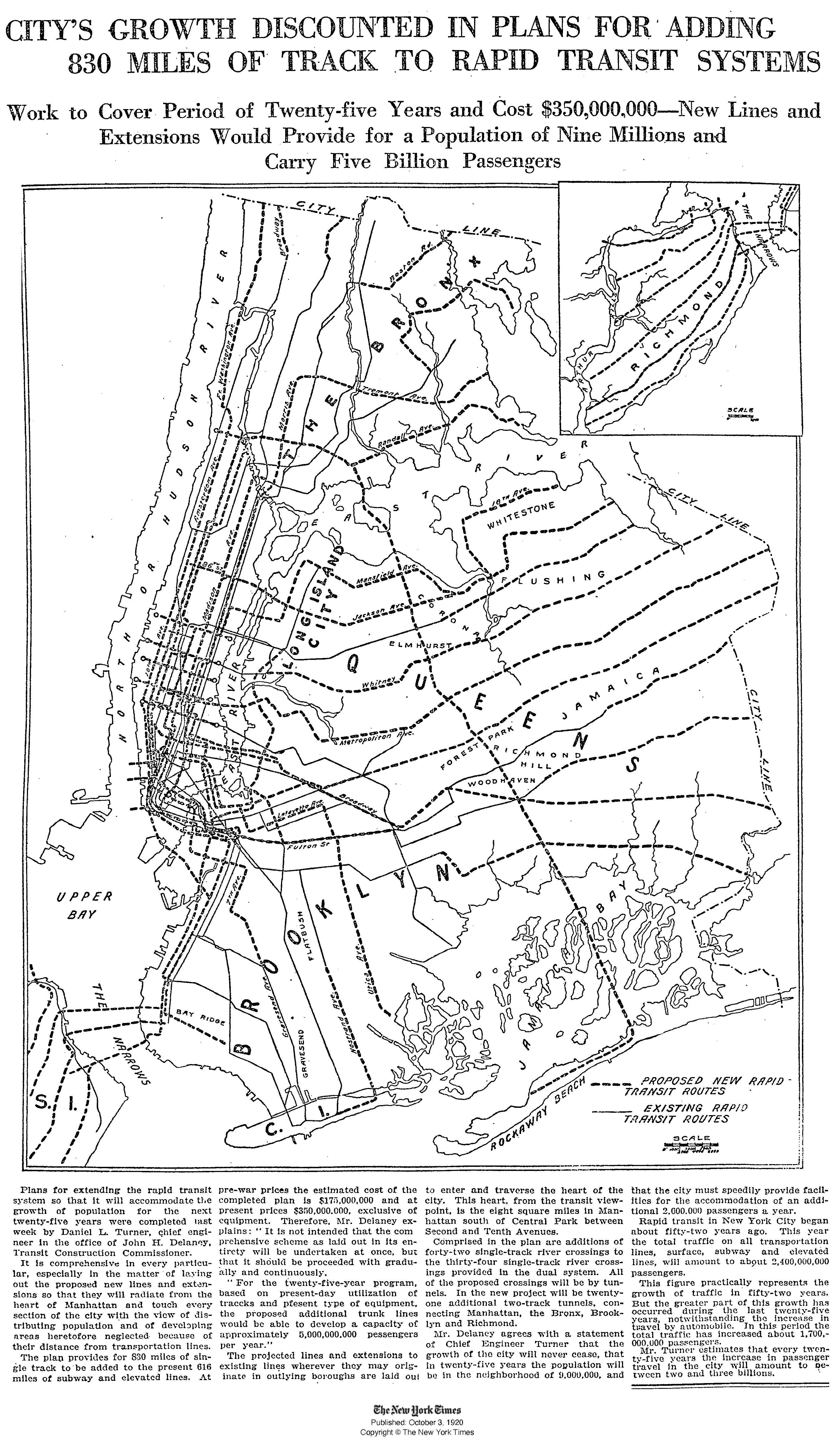

New York boasts not just its built subway system, 472 stations along 665 miles of revenue track, but also an impressive unbuilt subway system. As author Joseph B. Raskin described it, a 1920 city expansion plan — the City never formally committed to it — called for “five new trunk lines and nine new crosstown lines in Manhattan, eight new lines or extensions in the Bronx, thirteen new lines or extensions in Queens, fifteen new lines or branches in Brooklyn, and five new lines to serve Staten Island.” What happened to New York’s ghost subways to consign them to phantom memory? The popular notion is that 20th century urban villain Robert Moses consigned the blueprints to the shredder in favor of roads, and that after Moses departed, we stopped knowing how to build anything at all.

But the truth is more complicated, and interesting, and instructive. In fact, the demise of these expansion plans and so many others like them is proof that the problems that hamper good planning and building to this day — who is in charge? who will pay? — have been with us nearly from the start.

It once seemed so easy, or so the story goes: Using taxpayer dollars, construction contractors broke ground on New York’s first subway line from City Hall to northern Manhattan in 1900, and just four years later, riders were crowding the trains, run by the private-sector Interborough Rapid Transit. Over the next decade, the IRT expanded, and the City commissioned a different company, the Brooklyn Rapid Transit, to operate more lines. By the 1920s, the City, having grown disillusioned with private-sector subway management, planned and was soon building “independent” lines that it would run directly, finishing just as World War II began.

And that was just the start. If all went well, by the middle of the 20th century, according to that 1920 map, New York would add 830 miles to the then-616-mile underground and elevated trackage, capacity to carry five billion passengers annually. In Brooklyn, New Yorkers would traverse Utica Avenue by subway; from the East Bronx, they would move into Manhattan and down Second Avenue all the way to Brooklyn. Vestiges of these promises persisted for decades: As late as the early 1970s, Gov. Nelson Rockefeller and Mayor John Lindsay were promising a 48th Street crosstown line, and even Mayor Bill de Blasio, in 2015, offhandedly revived the Utica Avenue idea. But nothing happened, or almost nothing. Nearly all we got is a new train tunnel to Queens in 1989, a new stop on the 7 train in 2015 and three Manhattan stops of the Second Avenue Subway in 2017.

Before we lament the good old days, though, we must remember that, as Ed Koch once told a woman who begged him to return New York City to a more glorious era, “Lady, it was never that good.” Construction firms were able to build the city’s first subways so quickly in part because they imposed dangerous and disruptive conditions New Yorkers rightly would never put up with today. At least a dozen laborers died building the subways, and civilians were at risk, too. Consider the woes inflicted under just one construction subcontractor, controlled by one Major Ira A. Shaler, who earned the sobriquet the “hoodoo contractor” for his bad luck. As the Times chronicled in 1902, that January, a dynamite mishap had killed six people, including a “guest killed in his bed.” Five months later, Shaler himself, on an inspection tour with the subway’s chief engineer, William Parsons, was crushed to death by loose boulders. As for disruption: Early 20th century “cut and cover” subway construction routinely obliterated dense Manhattan blocks, as John E. Morris wrote in his subway history. As for operations: In 1918, the BMT, the BRT’s successor, dispatched an inexperienced strikebreaker to operate a train through a sharply curved tunnel. The resulting high-speed crash killed at least 93 people.

As Ed Koch once told a woman who begged him to return New York City to a more glorious era, “Lady, it was never that good.”

New York will (hopefully) never go back to holding human life, and quality of life, so cheaply — but there must be some decent path between accepting preventable deaths as the cost of doing business and accepting union agreements between today’s subway-construction contractors and labor unions that help push New York’s construction costs well above global standards. As New York University Marron Institute researchers have found, it’s possible to be a high-wage, high-productivity construction regime, and a safe one, too; Sweden was their example. But New York is a high-wage, low-productivity construction environment, and we can only surmise the reasons, as subway-related construction contracts, and thus the union work rules that govern job sites, are private agreements between private parties — the contractors and the unions — and thus not obtainable by journalists or the public.

High construction costs aren’t the only impediment to expanding New York’s transit system, though. The issues that have eroded New York’s ability to build much of anything, transitwise, have persisted for decades. They arose when things seemed to be going well, but it took time for the consequences to be clear.

First, governance. Who is in charge? The state and City have always fought over this responsibility, leaving the subways semiorphaned. As Raskin explains, the City’s ambitious 1920 plans sparked covetousness on the part of a newly elected governor, Nathan Miller. Miller didn’t like the idea of lucrative contracts under the control of the City’s political patron, the Tammany Hall Democratic machine. Miller thus created the state-controlled Transit Commission to take over. As Raskin writes, Mayor John Hylan “never fully accepted the Transit Commission’s authority, beginning three … years that stopped transit planning and construction cold.” It took the return of Gov. Al Smith for the City to wrest back control of its subways, in 1924. Over the next four decades, the state and City bickered fitfully, but neither side cared all that much, because not much was at stake: The City wasn’t building much transit, and the state had no interest in taking over the City’s burden of funding annual transit deficits. It wasn’t until 1968 that the City, then in charge of the barely decade-old Transit Authority, lost power to the state-controlled Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

This persistent public confusion of who is in charge of the trains hampers any political incentive to massively improve them. As former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo observed to me for my forthcoming book, “They put together the MTA to avoid responsibility. We can blame anybody but nobody … The trains suck, and they’re always gonna be late. Let’s come up with a political system where the MTA is to blame. Who is the MTA? Nobody is the MTA. Most people think it is the mayor.” Bill de Blasio, New York’s mayor from 2014 to 2021, concurred: “The MTA was built as a subterfuge to get people from blaming the elected officials.” There’s no blame, but there’s also no praise, so most elected officials — Cuomo was an exception, both for better and for worse — ignore the subway until a crisis arises.

Second, the suburban wedge. One reason that the state, not the City, took over the subways in 1968 was that three years earlier, the state had taken over the then-bankrupt Long Island Rail Road. It needed a way to offset railroad deficits, and the surpluses thrown off by Robert Moses’s Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, which Mayor John Lindsay separately coveted for the subways, attracted Gov. Nelson Rockefeller. The state simply threw everything — subways, buses and commuter rail — beneath the MTA umbrella. To this day, the commuter railroads get a disproportionate share of MTA investment, the political price of getting the Legislature to approve any infrastructure improvement; the now-“paused” congestion-pricing program, for example, would devote 20% of its dollars to suburban rail improvements (and 80% to the subways and buses). The MTA also maintains two entirely separate management structures for the LIRR and for the Metro-North Railroad, duplicative costs that consume finite fare and tax dollars mostly borne by the City’s tax and rider base.

Third, who will pay? By their second decade, the IRT and the BRT/BMT were falling into insolvency, because the City refused to raise the nickel fare to account for inflation. This failure — the fare didn’t rise until 1948 — presaged a longer-term cognitive dissonance, one that has persisted since the state takeover nearly six decades ago. Refusing to increase the fare wasn’t just politics; New York’s state and local leaders realized early that it wasn’t fair to ask riders to pay for the full cost of a subway ride, partly because some riders couldn’t afford it, and partly because other parties — real estate investors, employers — benefited from a functional subway.

Yet this mismatch between subway revenues and costs hampered the subway’s expansion after World War II; City money for transit improvements was instead diverted to operating costs. Robert Moses realized that problem; in 1945, he advocated for a doubling of a mooted City sales tax to 2%, with the proceeds to go to transit, calling it “the easiest way” to finance subway rehabilitation. “There’s no point in going into the question of a higher fare,” he said, as reported by the New York Herald Tribune, at a budget hearing, acknowledging the politics. “The easiest way would be to put the extra cent back on the sales tax and earmark the money for transit.” But the City and state (the latter’s approval needed for most tax increases) didn’t act.

The MTA can never focus on long-term planning and investment because every decade, it faces a deficit crisis that requires it to lobby the Legislature for yet another new dedicated tax.

More than a decade later, the state and City lost an opportunity to build a subway between Staten Island and Brooklyn. In 1956, when Moses’s Triborough Authority was about to spend $300 million building the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge between the two boroughs, transit planners and the press wanted him to spend extra money to make the bridge heavy enough to carry rail. Moses, calling the idea “preposterous,” pointed out that 30 years previously, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey had fortified the George Washington Bridge, but that no rail agency had taken advantage of this potential. He argued, too, that a rail link from Staten Island to Brooklyn would dump travelers onto Brooklyn’s Fourth Avenue subway, running at capacity even as ridership was falling. It would cost half a billion dollars, he estimated, to build enough rail capacity in Brooklyn to receive Staten Island passengers, money that Triborough’s finite surpluses could never cover — and the City’s Transit Authority would have no money with which to operate more trains. These were not insurmountable problems; the City and state could have approved a new tax to fund an increase in transit capacity and service in Brooklyn. But elected officials preferred to defer this politically fraught task, and the press was content to blame Moses.

It took nearly three more decades — and a crisis that threatened the City’s fragile, recovering 1980s tax base — for the state, prodded by then-MTA chairperson Richard Ravitch, to enact dedicated taxes to subsidize operations and fund capital investments on a consistent basis; those taxes have grown from five to nearly a dozen. Before COVID-19 reduced fare revenues, fares and taxes evenly funded most of the MTA’s operating budget. These taxes have kept up with inflation, but costs have far exceeded inflation, thus leaving a persistent mismatch. The MTA can never focus on long-term planning and investment because every decade, it faces a deficit crisis that requires it to lobby the Legislature for yet another new dedicated tax.

Fourth, fanciful planning. It’s easy to look at the 1920 subway map and mourn for what New York lost. It’s more realistic to look at it and think: We never needed all those promised subways, anyway. It’s impossible to fully separate cause and effect, supply and demand, but New York didn’t turn away from building transit and toward building roads as it finished its IND subway construction because of a Moses-driven plot to harm transit in favor of the automobile. It did so in part because once the automobile made living less densely possible, middle-class people demonstrated, in large numbers, that they wanted to live in less dense surroundings. Many people preferred a detached house in eastern Queens or south Brooklyn — or an even larger house with an even bigger yard on Staten Island — to two rooms in a Lower East Side tenement, and the City and its developers accommodated them. Yes, mortgage subsidies helped, but they were in part a response to public desire; they weren’t a conspiracy to force people to do something they didn’t want to do. Subways serving semisuburban densities are uneconomical, even with heavy subsidy.

***

New York doesn’t need to succumb to the myth of its irretrievable history. It can salvage what it needs from the myth to make the future better. Sure, build out the Second Avenue Subway. Gov. Kathy Hochul should proceed with the MTA’s plans to build the Interborough Express between Brooklyn and Queens, its costs partly defrayed by increasing density in the mile adjacent to the corridor. But we never really needed a 48th Street crosstown subway; a full, protected busway would achieve the same results. Far more ambitious plans are unlikely to succeed, unless transit advocates solve a puzzle that has perplexed for generations: how to get the person in charge — the governor — fully engaged in transit planning and execution, when, absent an immediate crisis, so few people vote based on the governor’s position on such a long-term issue.