Violence persists well above the unconstitutional 2015 levels

The crisis in context

Turbulent doesn’t begin to describe the free-fall collapse of New York City’s jails over the past few years. For those just joining, since 2015, the jails have been operating under a federal consent decree, after the court found that the levels of violence had reached unconstitutional levels. A monitor with broad and deep experience in the operation and reform of correctional facilities, Steve Martin, was appointed to oversee the City’s compliance with approximately 300 provisions setting out the standard the City must reach to regain independent governance.

Thousands of pages of detailed instructions have been filed and countless hours of consultation and observation have passed. But the monitor is just that. He does not have the operational authority to execute. Since 2015, the department has been rocked by the COVID-era “sick-out” of up to a third of the workforce, a rash of deaths (33 in the last three years) which in their manner — an incarcerated person bleeding out in the presence of officers, another choking to death on an orange in an unstaffed unit — pulled back the curtain on the deep dysfunction with which the department is riven. Eventually the monitor, aware that the department was unable to move toward sound correctional practice, instructed leadership to focus simply on four basic tenets: security, accountability, management and training. That is, everything. Rebuild from the ground up.

When Vital City last checked in for a regular report on the jails’ health in early 2023, we noted the broad and disturbing levels of violence, well above the 2015 unconstitutional levels, in spite of ample staff and budget. 2023 turned out to be the most remarkable year, reaching a nadir in the relations between the federal oversight and the city. In May, the relationship unraveled completely in the face of the commissioner’s defiant mendacity: hiding from the monitor a death and a series of life-altering injuries suffered by incarcerated people over just a few days.

The contumacious behavior was reflected not only in an actual finding of contempt by the court but by an escalating number of orders and reports trying to bring the department into line with some basic rules like: do your job, obey court orders. The drumbeat of reports from the monitor and orders from the court reached battle speed in 2023 and 2024. The 21 reports from the monitor in that short period exceeded the number filed in the previous three years, while the court issued nine orders to try to get some basics in place, representing approximately 75% of the orders issued since the consent decree in 2015.

Among the flying papers was a filing that has the potential to be a watershed: a request by the plaintiffs and the United States Attorney to appoint a receiver, a person who can not only watch and suggest but who can execute on policy where the City has been unable and unwilling to do so.

In December 2024, the mayor appointed a new correction commissioner, and an audible sigh of relief issued from the court and the monitor. The court purged the contempt finding, crediting the Monitor’s assessment that “’the Department has made important strides in returning to a more collaborative and transparent relationship….” But, as in every document that has issued from the court or the monitor in this case, the coda was minatory:

[I]t remains essential that the Department continues to work toward structural transformation that will promote sound correctional practice in accordance with the Monitoring Team’s repeated exhortations. The level of danger posed to individuals in custody and employees at Rikers Island is still unacceptable, and the Court continues to expect nothing less than rapid changes to ensure the safety of those who live and work there.

What now? The public psychodrama has receded but the violence continues. It is a problem of governance, as the monitor has noted for close to nine years now. If the City can’t do it itself, if the monitor’s weight is unequal to ameliorating the appalling violence, then another way must be found, one that is endowed with sufficient power and nimbleness to make change with a speed that matches the problem.

-Elizabeth Glazer

What the numbers reveal — and conceal

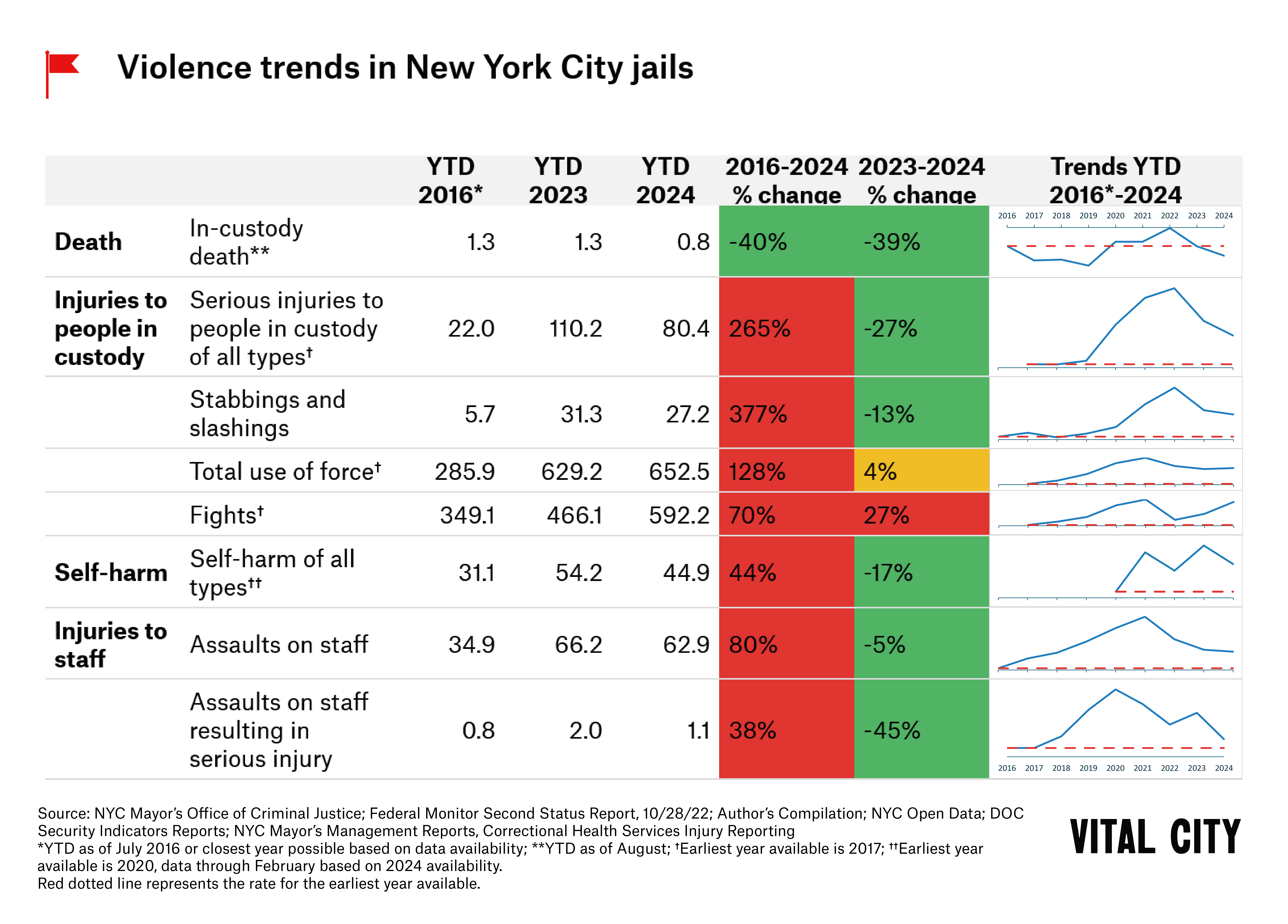

At the end of 2023, the New York City Department of Correction (DOC) teetered on the brink of receivership with violence rampant in its facilities, basic needs unmet and ongoing questions about the accuracy and completeness of the information being shared with oversight bodies and the public. More disturbing were well-founded doubts about whether the department’s leadership was acting in good faith to remedy problems and work in partnership with the federal monitor and others. While the first half of 2024 has given some reason for hope in the form of new leadership and better engagement with federal authorities and others, perhaps most evident is what has not changed. Even with the incremental improvements in most metrics of violence from the COVID-era peaks, violence remains two, three and more times higher than the unconstitutional levels of violence that led a federal court in 2015 to put the City and the jails under the supervision of the federal court and a monitor (Nunez v. City of New York). One bright spot is a drop in death rates; however, given the lack of progress on other metrics, it is difficult to know whether that will be sustained.

Following periodic previous reports, here Vital City assesses the state of New York City’s jails at midyear, pointing to what has and has not changed, and what New Yorkers might expect over the coming year.

But first, an important note about the data

As in our last report on the state of the city jails, we note with a red flag where the reliability of the numbers is uncertain. The federal monitor has raised serious questions about the Correction Department data, including even information as critical as in-custody deaths or as seemingly objective as stabbings and slashings. The questions about obscuring of information, as a result of intention or incompetence, infects many aspects of the effort to measure the quality of life in the city’s jails. For example, a recent lawsuit alleges that DOC staff coerced or falsified reports regarding refusal of medical care. DOC’s failure to publish information in a timely and regular fashion results in delays in when data is made available to the public, even when the dates are legally mandated. As of this writing, the department’s own monthly dashboard had not been updated since May.

If the publication of information is slow and uncertain, the December 2023 change in commissioners may be bringing some long-absent transparency, according to the federal monitor. To the extent that the data available to the commissioner and to her team is reliable, this could be progress. Our tentative assessment is grounded in the continuing reporting omissions, inaccuracies and inconsistencies in the data as reported by the monitor. Transparency is an irreducible minimum of good governance. But governance is undermined when the data proffered is not accurate, no matter the good intentions.

With all these cautions, Vital City is presenting the data we have as context for conditions on Rikers. Where there is documented concern with the accuracy of the numbers, the reader will see those charts marked with a red flag.

While violence has dropped compared to this time last year, it remains alarmingly elevated compared to 2016

1. Jail population, staff and budget

New York City is one of the most richly staffed jail systems in the nation. Although the number of uniformed staff has fallen in recent years, those declines have not matched the precipitous drops in the jail population since its peak in the early 1990s. DOC currently employs one uniformed staff person for every person in custody. While that is a significant decline from FY 21, when the department employed 1.7 uniformed staff per person in custody, it is more than 1.5 times the department’s staffing ratio in the 1990s and four times the national average. Despite this high staffing ratio, the department has launched an intensive recruitment campaign, including videos in taxis and ferries, ads on streaming services, and messages from the Commissioner on 311, among others. So far, this has resulted in two new classes of recruits and a total of 177 new uniform staff members. Training for these new officers continues to be abbreviated — academy training time was cut in half in 2023 and has not yet been restored, despite the continuing dysfunction and violence in the facilities.

The ratio of uniform staff to people in custody remains high

Despite a wealth of personnel, the department has struggled with maintaining adequate staffing in the jails in recent years, leading to double and triple shifts. There has been considerable progress in the past few months, with February 2024 marking the first time the department has had no unmanned posts or triple tours since the monitor began tracking them in 2022, and reductions in the percentage of the workforce out sick or unable to work with people in the jails. At the height in 2021, 27% of the workforce was out sick or unable to work on a given day. While reduced drastically from that peak, the number of staff unavailable to work is still above pre-pandemic levels, and out of line with other workforces. The department maintains the highest sick rates of any City uniformed workforce, with total absence rates of almost 12% in the first four months of FY 24 compared to 9% for the Fire Department, 4% for NYPD, and 8% for the Department of Sanitation.

Has the return of some staff to work had a meaningful impact on conditions or violence in the facilities? The bare numbers are not encouraging on this, perhaps highlighting the monitor’s oft-repeated warning that training and implementation on sound correctional practices — that is, that staff are doing their jobs — is the fundamental foundation to violence reduction. For example, in one of his most recent status reports the monitor stressed that officers and captains continue to fail to conduct regular and meaningful tours of facilities as required by the department and the Action Plan. He stressed that this failure “has contributed to the units’ overall state of dysfunction and has resulted in the use of unnecessary and excessive force and serious acts of violence…[and] has also been identified as a contributing factor to several deaths in custody.” For example, the Board of Correction found that correction officers failed to complete required tours in two of the four deaths that occurred in the second half of 2023, the deaths of William Johnstone and Curtis Davis.

Department of Correction uniformed staff absence rates peaked in the aftermath of the pandemic, but are now on the decline

The department’s efforts to ensure that all posts are staffed have also not yet translated into ensuring that the needs of those held in the jails are addressed. There were more than 12,200 missed medical appointments in May 2024 alone — roughly one in four scheduled appointments — and this was by no means an outlier. While more than half of those missed appointments are classified as instances where the person refused care, a new lawsuit casts doubt on those numbers, alleging that people held in jails were pressured to sign false refusal forms or were unaware of the existence of appointments that they had been recording as refusing. These allegations are particularly troubling in light of claims that the most recent DOC death in July came after correction officers repeatedly blocked medical staff from providing care.

Thousands of people in custody miss medical appointments each month, and doubt has been cast on the veracity of classifications that people refused care

While missing medical appointments can lead to grave immediate consequences, failure to receive care over longer time periods can mean that even initially minor medical complaints may escalate, resulting in serious risks to the health and safety of those incarcerated. The affidavits of people in custody filed with the record falsification lawsuit are replete with such instances. Kevin Gamble, for example, described experiencing uncontrolled diabetes for much of the year after the department failed to bring him to 212 medical appointments over 195 days to receive his regular fingersticks and insulin injections. Among many other reasons, this is why the extraordinary lengths of stay are so troubling.

Jails — where people, innocent until proven guilty, are held awaiting trial or other disposition of their cases — are not designed for long periods of incarceration and do not typically have the requisite facilities or programming for long-term stays. Despite this, more than 1,300 people currently in custody have been held for a year or longer, equating to more than one in five of the jail population. Of those, more than a third — roughly 500 people — have been held for two or more years.

More than a fifth of the jails’ population is held for a year or more

Lapses in care and inadequate programming for those in custody are not the result of a lack of funds. DOC spending has increased significantly in recent years, a trend that continues this year. In FY 2024, the City spent an average of $474,191 per person in custody, an increase of more than $30,000 from last year.

Spending per person in custody remains at record highs, increasing from last year

2. Death and violence

If those funds have not bought better medical care or programming, nor have they succeeded in buying greater safety for those incarcerated or working in the facilities. Since 2015, the jails on Rikers Island have been operating under a consent decree enacted to remedy unconstitutional levels of violence and other dangerous conditions, a settlement in the case of Nunez v. City of New York et al. Under the consent decree, a federal court and monitor reporting to it oversee the DOC’s attempts to make things safer and more humane for those incarcerated and those working inside. So far, these efforts have not succeeded.

Across a wide range of metrics, the jails are more dangerous than they were when the federal monitor was put into place. While violence has largely been on the decline from the peaks following the COVID pandemic, with few exceptions it remains elevated well above the already unconstitutional rates of 2015.

More disturbing is that even these elevated numbers might be artificially low. As we warned in the red flag note that accompanies this report, whether the information being shared by the DOC can be relied upon is in real doubt. Nowhere is that more true than with data on violence. In one of his recent reports, the monitor highlighted a 49% drop in stabbings and slashings from January to February 2023 following the issuance of a DOC memo that suggested to staff that not all serious violence needed to be reported at the discretion of staff. The monitor further identified the failure to classify a number of stabbings and slashings as such. The troubling conclusion to be drawn is that it was the assessment that changed rather than the violence — that stabbings and slashings did not, in fact, drop by half, but rather staff were, at their discretion, choosing not to classify them as such.

Stabbings and slashings have historically been used as markers of violence in part because they were, in the past, considered less subject to reporting discretion — each stabbing and slashing must be recorded by DOC and/or medical staff. That these too may now be unreliable amplifies existing concerns about the extent to which levels of violence can be meaningfully assessed in the facilities. Vital City continues to present the violence data available as some indication for conditions inside, but we also continue to make note of places where issues with the data have been documented.

A. Deaths

2024 has seen a continued drop in in-custody deaths, with a year-to-date rate almost identical to the start of the monitoring period in 2015. However, the current rate remains elevated both when compared to what the department was able to achieve in the years leading up to the pandemic, and in comparison to national jail death rates. Deaths are rarer events this year than in other recent years. Nevertheless, almost every death reveals significant mismanagement, lack of supervision and accountability.

In-custody death rates have continued to drop

B. Injuries among people in custody

By all other available metrics, rates of violence continue to be elevated: among people in custody, against people in custody by staff and against staff by people in custody. As before, these high rates of violence among people in custody are notable by both the most serious metric — stabbings and slashings — and the broadest, fights.

Both the Board of Correction and the monitor have raised major concerns about the accuracy of the department’s reporting regarding serious injuries to those in custody. Yet even by DOC’s own accounting, rates of serious injuries to people in custody this year to date are 3.7 times higher than they were at the same point in 2017, the first year for which year-to-date data are available.

Serious injuries to people in custody dropped — but the numbers remain in question

Stabbings and slashings remain alarmingly high and it is possible that even these numbers underestimate their true rate of occurrence. In FY 24, while stabbings and slashings continued to drop from a historic high in FY 22, the pace of improvement was slower than in FY 23. Moreover, the rate remained 338% higher than when the consent decree was put into place and 4,093% higher than at its lowest level in FY 08.

i. Stabbings and slashings

The pace of improvement in stabbings and slashings slowed from last year – and again the numbers continue to be in question

Monthly stabbing and slashing rates show largely the same story. While there have not been the same kind of dramatic spikes seen in previous years, the numbers remain alarmingly high. The number of incidents in June 2024 was higher than at any point prior to March 2021, even when the number of people in custody was considerably larger.

Viewed by month, stabbings and slashings remain well above 2016-2020 norms — and the numbers are in question

The monitor continues to track violence and other key metrics by facility, as doing so is crucial to identifying hot spots. While looking at the numbers can aid in tracking the progress of violence-reduction efforts, a more granular look is necessary before conclusions can be drawn: It is possible that problems may simply have been shifted to other facilities or people kept in lockdown. (As in our last report on the state of the jails, facility census numbers are not available, so we are limited to showing total stabbing and slashing incidents rather than rates.)

The number of stabbings and slashings continues to vary across facilities, with most incidents occurring in five facilities or units: the Eric M. Taylor Center (EMTC), George R. Vierno Center (GRVC), Otis Bantum Correctional Center (OBCC), Robert N. Davoren Center (RNDC) and Rose M. Singer Enhanced Supervised Housing (RESH), a highly restrictive unit intended to curb violence for those most at risk.

Violence varies across jail facilities but is concentrated in five

ii. Other injuries to people in custody

Violence against people in custody includes violence by staff against incarcerated people. Findings of “excessive and unnecessary use of force” by correctional staff were central to the imposition of the federal monitor and have been under close scrutiny since the consent decree’s inception. Annual use of force rates show that in FY 24, the department continued to make incremental progress in reducing use of force from a dramatic rise and peak in FY 21. Yet the total use of force rate in FY 24 was more than double the rate in FY 16, when the federal monitor was installed, and 350% higher than in FY 13, the earliest year data is available.

High levels of force being used against people in custody is itself cause for concern, but there are also real questions about whether the extent to which people in custody are being harmed by use of force is being obscured. The data on use of force with serious injury tells a different story than overall use of force — or indeed than any other violence metric available — which is cause for some skepticism. There was a considerable drop in reported use of force with serious injury in FY 24. That alone wouldn’t necessarily raise eyebrows, but a closer look at the monthly data shows a dramatic drop in use of force in August 2023 followed by continuously low rates to date. The consistency of the rates since the remarkable drop is unprecedented since use of force with serious injury began being reported in July 2016. That unusual result, coupled with serious concerns raised by both the monitor and the City’s Board of Correction about the accuracy of the department’s reporting of serious injuries to people in custody raises real questions about whether, in fact, people are being seriously injured by staff less often or if, instead, those incidents are being unreported or classified in other ways.

Progress in reducing alarmingly high rates of use of force remains incremental — and the numbers are in question

When examined month-to-month, total use of force remains elevated — and the numbers are in question, particularly when it comes to serious injury

Fights among people in custody have continued to rise over the past six months. The rate of fights in 2024 to date is not only 68% higher than it was at this time in 2017 (the earliest year that a year-to-date rate can be calculated), but is 26% higher than it was in 2023 and 43% higher than in 2022.

After dropping briefly in 2022, fights among people in custody continue to increase

iii. Self-harm

The rate at which people in custody harm themselves is also critical for understanding the state of conditions in the jail facilities, and has been closely watched by the monitor. Self harm alone is troubling, yet in a recent report, the monitor raised the further spectre that “eight people have died by suicide or suspected suicide…since the Court required the Department to improve its practices regarding self-harm in September 2021.” In looking at the data made available since our last report, there is some indication that self-harm rates are going down, but rates are still high, and there have continued to be significant fluctuations month-to-month.

There are some indications that self-harm is decreasing, but a consistent pattern has not been established

iv. Injuries to staff

Violence in the jails does not only affect people in custody; people working in the jails also continue to be at risk of harm. The pace of progress in reducing assaults on staff seems to have slowed, with the rate of assaults on staff as of mid-year 2024 remaining almost double what it was at the same time in 2016. In part, this is due to an increase in assaults in the past few months, but it remains to be seen if this trend will continue.

Progress in reducing assaults on staff has slowed and rates remain elevated

Assaults on staff that result in serious injury remain an infrequent occurrence, and it appears that the department has continued to make progress in reducing them still further this year. As of mid-year 2024, the year-to-date rate is the lowest it’s been since 2017, a trend that will hopefully continue.

Assaults on staff resulting in serious injury remain infrequent and continue to decline