Rikers Island remains a mismanaged hotbed of violence.

With the city’s jails now entering the 11th year of a federal consent decree aimed at stemming the violence, the brutal conditions there are markedly worse. In a macabre version of Groundhog Day, each report from the federal monitor brings further bad news about the “concentric circles of dysfunction” that have been impervious to the efforts of the three mayors and five commissioners tasked with fixing the jails since the 2015 agreement.

The judge overseeing the consent decree has noted what cannot be denied: Something is very wrong with the city’s jails, something that is beyond ordinary efforts to fix. “Not only has the pace of reform not accelerated…but progress has even slowed or regressed in many areas.” She has ordered the City, the plaintiffs and the United States Attorney’s Office to confer on the scope of powers of a federal receiver, an exceedingly rare remedy, instituted as a last resort with the power to fix the jails — to be sure, only if exercised with great skill — in a way a commissioner and even a mayor cannot. As of this writing, whether the court will order this remedy and if so, what powers and reach the receiver will have, are still under discussion.

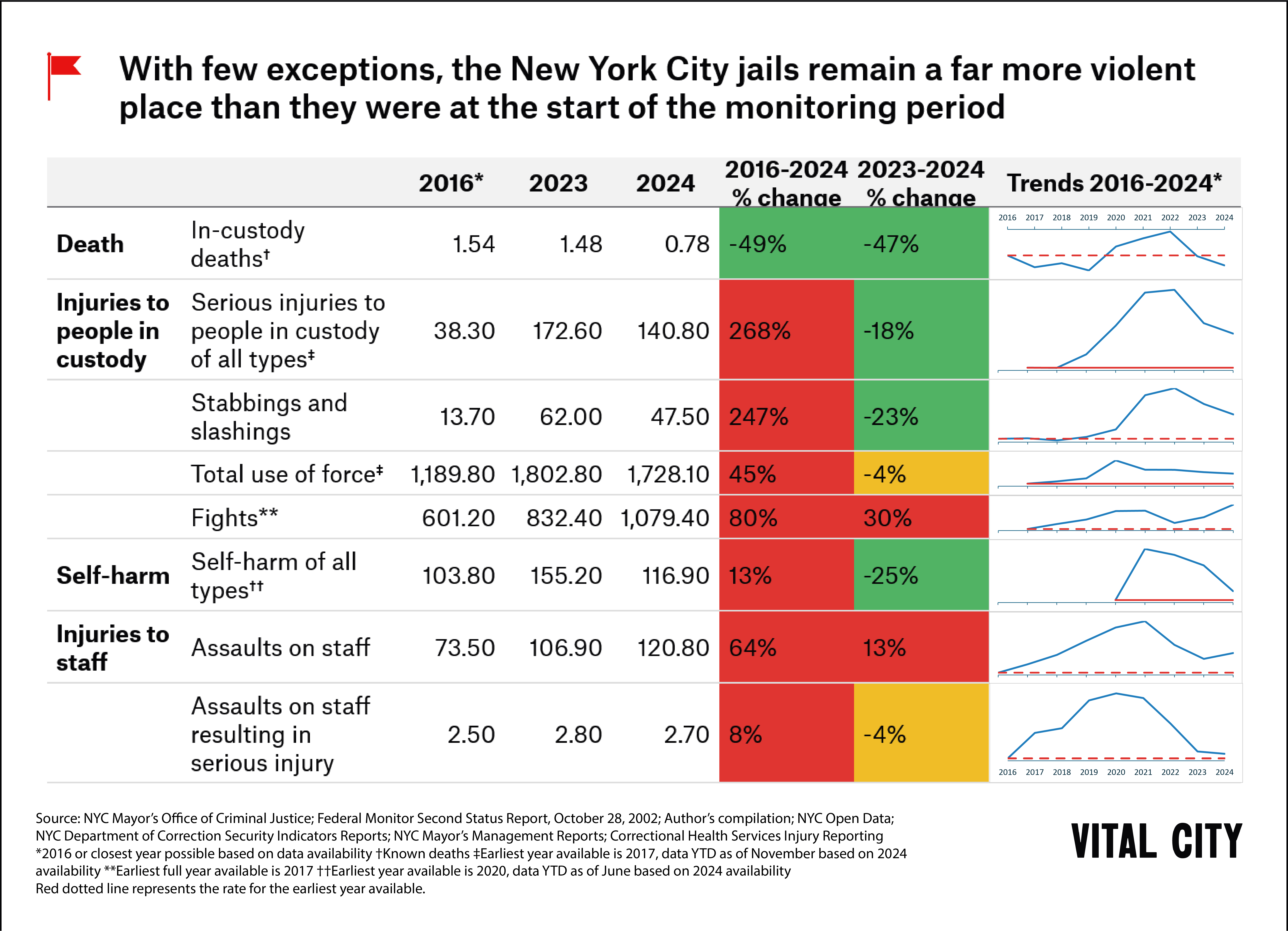

We offer this report to document where the jails are, as we have done regularly, and to assist anyone engaged in the project of diagnosing and fixing the jails with some basic information on the conditions inside. By almost all metrics, violence in the jails is elevated well above the already unconstitutional levels that marked life inside when the City first entered into a consent decree with the federal government in 2015. Rates of violence among people in custody, against people in custody by staff, and against staff by people in custody are all up, often by astronomical levels. While matters have improved in some areas between 2023 and 2024, the improvement is an extraordinarily modest reduction compared to the overall deterioration in conditions since 2016. In other areas, progress has stalled or conditions are worse: Both fights and assaults on staff were more common in 2024 than they were in 2023.

As in our last two reports on the state of the city jails, we note with a red flag where there are questions about the reliability of the numbers. The federal monitor and others, including the Board of Correction, have raised serious concerns about the accuracy of Department of Correction data, including even information as critical as in-custody deaths or as seemingly objective as stabbings and slashings and other serious injuries. These issues range from failure to provide timely data, even when the dates are legally mandated, to allegations of the deliberate falsification of records on access to medical care. Whether intentional or not, major gaps in the availability of reliable data can obscure key points about the state of New York City’s jails and their inhabitants.

So how did we get here, and where do we go now?

1. Jail population, staff and budget

In 2021, after more than two decades of a steadily shrinking jail population, the number of people in jail started to rise. Compared to the low of 3,809 people in jail in April 2020, following a concerted effort by every part of the justice system to confine only those who posed the most risk, today the average daily population is 6,605. The rise in the number of people in jail does not seem related to the crime rate: 2017-2019 marked both new lows in incarceration and crime, and marked a period of steadily declining both crime and incarceration. Today’s jail population of 6,605 is about the same as in 1978 when the murder rate was 4.2 times what it is today.

The number of people incarcerated is inflated by ever-increasing lengths of stay. The size of the jail population on any given day is determined both by how many people enter the system and how long they stay. After a precipitous drop in admissions in 2020 due to bail-reform legislation and the COVID-19 pandemic, more people are now being admitted each year, with 43% of those admissions for violent felony offenses in 2024.

The amount of time people are spending in jail has increased dramatically over time as case-processing times have increased. From the late 1990s, when the jails were overcrowded and demands on the courts much higher to 2016, the average length of stay hovered around 50 days, give or take six in either direction. A much sharper upswing started in 2017, with the biggest spike occurring following the effective shutdown of the courts during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Stays have only modestly shortened since then, and length of stay for people in custody remains a persistent, far-reaching problem. Lengths of stay in FY 2024 were more than double the amount of time people were held in jail in the late 90s and early 2000s, and improved by only three days from FY 2023. While a larger proportion of people in custody are held on more serious charges than in earlier years, that alone cannot explain the increase in the time they are held: Length of stay for serious charges has also increased. People facing felony charges were held for 69 days on average in 2000, compared to 125 days in 2023. The Office of Court Administration recently announced a major initiative aimed directly at speeding up case processing times, starting in Brooklyn this year and rolling out to the rest of the city early next year. If they are successful in reducing length of stay to even 2019 pre-pandemic levels, the impact on both the jail population and conditions for those held inside will be substantial.

Even with increasing admissions and longer lengths of stay, the jail population remains well below its pre-COVID size. At the same time, the Department remains richly staffed, employing almost one uniformed staff member for every person in custody. Yet despite having a staffing ratio almost four times the national average and 1.5 times higher than in the 1990s, the Department continues to have trouble adequately staffing its facilities. Unmanned tours continue to be a notable contributor to violence, and triple tours are again on the rise after being eliminated in late 2023. The Department continues to have the highest sick rates of any uniformed workforce in the city.

The Department’s problems do not stem from a lack of resources. As both the jail population and the uniformed workforce decreased, the Department’s budget instead increased. For the past few years, it has been around $450,000 per person in custody, an increase of almost 200% from FY 2013.

2. Conditions in the facilities

Violence continues to be rampant in the facilities, putting both people in custody and staff at serious risk of injury. Judge Swain noted that “the current rates of use of force, stabbings and slashings, fights, assaults on staff, and in-custody deaths remain extraordinarily high, and there has been no substantial reduction in the risk of harm currently facing those who live and work in the Rikers Island jails.” Stabbings and slashings are a striking example of this trend: These rates have skyrocketed in recent years, more than quadrupling since the start of the monitoring period.

The rate of uses of force by staff against people in custody also remains alarmingly high, more than doubling since the start of the monitoring period. Moreover, the rate of progress in decreasing uses of force has slowed considerably over the past two years after a substantial drop following the peak in FY 2021.

These dangers are all the more concerning in light of the difficulties of obtaining medical attention in the facilities. In the third quarter of FY 2024, the most recent period available, people in custody made it to only two in five of their scheduled appointments. Almost half of scheduled appointments were missed because the Department failed to bring the person in custody to the service. Access to mental health care is only moderately better, with people in custody making it to roughly half of their scheduled appointments, while the Department fails to produce them in just under one in three.