What happens to maintenance and expansion if these billions fail to flow

Congestion pricing seemed like a foregone conclusion when Vital City ran an issue on the topic only last month. Now it could well be dead: Gov. Kathy Hochul announced she’s indefinitely postponing it and, for now, looking to find another, unspecified, source for the $1 billion a year it would have generated for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. She told state activists and lawmakers to be “imaginative.” It’s unclear whether the program will be canceled after all — City Comptroller Brad Lander and virtually every urbanist advocacy group in the region are suing, arguing Hochul has no authority to cancel the program after having signed the state law mandating it.

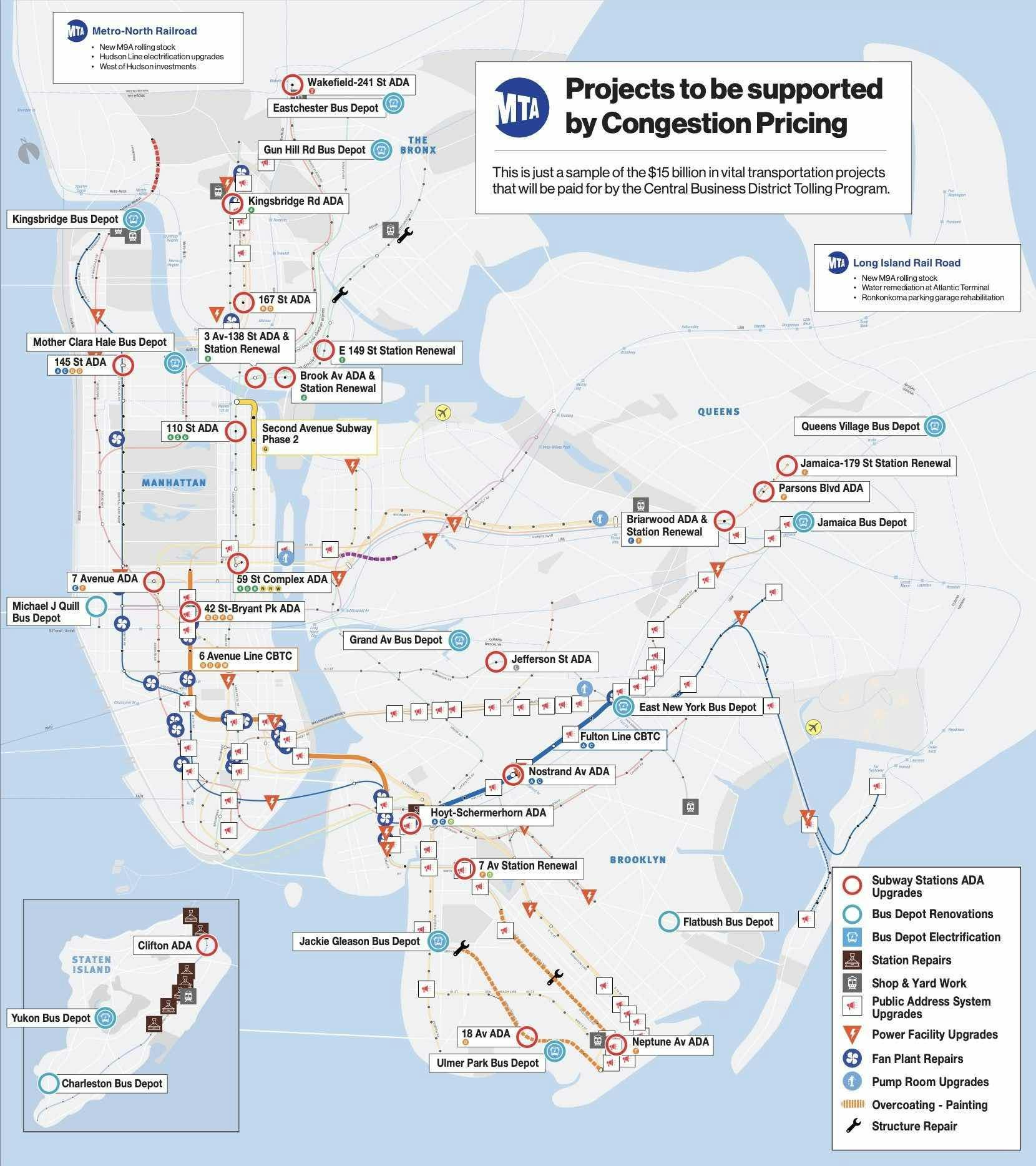

If congestion pricing is indeed indefinitely postponed or totally scrapped, what is at stake for those who rely on the subways? I took a closer look at the expected contribution of congestion pricing to the MTA capital program and the bind the MTA finds itself in with the money yanked so suddenly.

How much money is to be raised?

The law requires that congestion pricing produce a minimum of $1 billion a year. The MTA has heavily counted on this money, bonding against future revenue. And the 2020-2024 capital plan — which reflects the Authority’s plans for construction, maintenance and other costs supported by capital dollars — already has factored in $15 billion from those bonds. Effectively, the MTA has already spent the money, so without congestion pricing, the MTA has to massively cut future programs to pay back the bonds. Worse, the bond rating of the MTA depends on the reliability of its revenue stream; one of the credit agencies even said that it will reduce its rating, forcing it to pay higher interest rates, if in the next few months there is neither congestion pricing nor a comparable revenue stream from another source. Bondholders are signaling mistrust in the state’s ability and willingness to fund the MTA on this going forward, costing the agency $300 million a year in higher borrowing costs if Hochul’s decision is not reversed.

The overall size of the congestion pricing program has been a matter of controversy. Congestion pricing opponent Rep. Josh Gottheimer (D-NJ) has claimed that the total receipts will be not $1 billion a year but $3.4 billion a year. Regional data on travel volumes to Manhattan south of 60th Street, collected in the Hub Bound report, put the number of vehicles entering the Manhattan core at 728,000 per weekday in 2019. Fewer than a quarter of those used tolled entries, which would get credit for congestion pricing; the rest would be paying the full $15. If those projections pan out, the yield would be somewhat less than $3 billion a year, taking into account exemptions and future traffic reduction. If Gottheimer is right and the revenue will be $3.4 billion a year, then congestion pricing will permit the MTA to keep spending money on future capital plans at the same rate as in the 2020-2024 capital plan, using the program as a consistent funding source for expansion. (The 2020-2024 capital plan is about to be completed; the next one, for 2025-2029, isn’t out yet — and its scope will depend largely on congestion pricing and other revenue streams.)

Effectively, the MTA has already spent the money, so without congestion pricing, the MTA has to massively cut future programs to pay back the bonds.

What does the capital plan pay for?

Most of the capital plan pays not for discretionary expansion, but for ongoing long-term maintenance and system renewal. More precisely, MTA capital programs are divided into three categories:

1. State of good repair (or SOGR)

2. Normal replacement

3. Expansion

SOGR projects fill in the backlog of the years when the MTA had put off regular maintenance to save money, also referred to as “deferred maintenance.” This catch-up was the centerpiece of MTA capital investments in the 1980s and ’90s, as the city sought to recover from the years of neglect of trains and stations during the nadir of the late 1970s and early ’80s. Normal replacement refers to replacement of capital at its usual rate — for example, purchase of new trains on schedule. These days, SOGR is not too different from normal replacement in practice as the MTA catches up from the disastrous period of deferred maintenance and is simply getting back to a rhythm of replacing parts on a schedule instead of stretching them beyond reasonable use. As a result, system reliability is high by the standards of 40 years ago.

Together, SOGR and normal replacement comprised 75% of the New York City Transit share of the 2020-2024 capital plan. MTA chair Janno Lieber said as much in his press conference about the congestion pricing cancellation earlier this week.

Renewal funding cannot responsibly be cut. To do so would defer maintenance, leading to severe problems with the state of the fixed plant years down the line, as happened in the 1970s.

This leaves expansion as the remaining place to cut. A fair amount of the capital plan falls in this bucket. A total of 15% of the plan goes to MTA Construction and Development, which oversees the largest projects, such as the Second Avenue Subway. The rest is distributed to operating agencies under the MTA, of which by far the largest is New York City Transit; of New York City Transit’s share, 25% goes to expansion and the rest to renewal. For this, the MTA helpfully provided a map of its ongoing expansion plans, all of which are threatened by the delay or cancellation of congestion pricing.

But upon closer inspection, many of these projects cannot be cut legally, or can, but at the cost of forgoing even more outside funding.

The ADA consent decree

The bulk of the expansion program that congestion pricing is earmarked to support goes to installing elevators at stations. Of the total budget of the New York City Transit capital program for 2020-4, 26% went to stations, and a large majority of that sum went to upgrading 70 stations to make them accessible to wheelchair users, through installing elevators to complement stair and escalator access. This figure represents an acceleration over previous capital plans, as pushed both by Andy Byford when he was in charge of the subways, and by lawsuits over the MTA’s lack of accessibility as mandated by the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The lawsuits led to a consent decree, finalized in 2022, which states a minimum percentage of the capital plan that must go to station accessibility upgrades. At the current spending level, as set out in the 2020-2024 capital plan, this minimum is 14.69%. At the reduced spending level forced by the cancellation of congestion pricing, this cost would still constitute at least 12% of the capital budget. The same consent decree assumes that SOGR and normal replacement remain 75% of the total capital budget, so in effect, it requires the MTA to spend about half of its expansion budget on ADA accessibility. This cannot be legally cut.

The bulk of the expansion program that congestion pricing is earmarked to support goes to installing elevators at stations.

If the recommendations we have made at the Transit Costs Project for improving procurement to reduce construction costs are implemented, then we expect the cost of accessibility to fall dramatically — perhaps in half from project delivery alone — but then the MTA is legally required to spend the same amount of money on making twice as many stations wheelchair-accessible. The consent decree gives the MTA until 2055 to make almost — but not quite — the entire system accessible; the only reason the MTA is getting so much time, where comparably old subway systems such as Berlin’s are planning on full accessibility this decade, is that the cost per station is high. Any increases in efficiency will have to be plugged into better accessibility faster, rather than into cutting the overall budget.

Second Avenue Subway

Other than the ADA program, the biggest expansion item in the capital plan is the construction of the Second Avenue Subway, now in its second phase. This is a long-term project, with an expected completion date in the 2030s, but much of the spending on it is already done in the current plans, and the 2020-2024 capital plan alone includes $4.6 billion out of the $7.7 billion the plan projected for the line, $3.4 billion of which came from federal sources. The Federal Transit Administration may well pull the money if there is no local match. Between this threat and the strong public support for Second Avenue Subway, it is not feasible for the MTA to cut this project.

Some economies can be found through reforms to reduce capital costs, and have been. But this late in the process, they only amount to about $1 billion of the cost of Second Avenue Subway Phase 2, not enough to replace the lost revenue from federal funding. The savings come from shrinking the station footprint, but after over a decade of design around larger footprints, a last-minute change would not save more money than this.

In the future, subway expansion from the ground up can be made cheaper with this saving, by perhaps a factor of two, but without regular funds for system expansion, there won’t be any projects that could make use of this efficiency.

Renewal funding cannot responsibly be cut. To do so would defer maintenance, leading to severe problems with the state of the fixed plant years down the line, as happened in the 1970s.

Future prospects

The 2020-2024 capital plan is nearly complete. It cannot be cut, since nearly all of the money in it has been spent already, and if there is no congestion pricing money, then the MTA will have to scramble to pay the bonds and dramatically shrink the scope of future capital plans. With no real ability to shrink ongoing maintenance, wheelchair accessibility or the Second Avenue Subway, there isn’t much else to do.

Hochul’s favored expansion project after Second Avenue Subway, the Interborough Express connecting Brooklyn and Queens, is unfunded, and likely dead if there’s no source of money identified to replace congestion pricing. Even killing IBX is unlikely to be enough to put the MTA capital plan in the black.

With no appetite for the new taxes that Hochul tried to float as an alternative to congestion pricing, what is likely to happen is that the future capital plans will cut where they cannot do so responsibly: the long-term maintenance and renewal budget.

In other words, Hochul’s last-minute postponement or cancellation of congestion pricing could well result in not just the death of capital expansion that the governor strongly advocated for until last week, but also in underinvestment in the existing system. Trainsets, signals, and station facilities are going to be stretched slightly beyond their intended life. One year of shortfall is not the end of the world, but 20 would lead to a death spiral like that of the 1970s, all because the governor made a political miscalculation and intervened at the last minute to effectively cancel the state congestion pricing plan she herself had signed.