2025 will likely continue one of the most stubborn patterns in crime.

As 2024 comes to a close, New York City continues to grapple with the complexities of gun violence. By Dec. 29, 2024, the city had recorded 899 shooting incidents, a 7.7% drop from 2023.

The undeniable reality is the overall downward trajectory in gun violence since the peak of 1,562 shootings in 2021. That year’s spike, fueled in part by the social and economic upheavals of the COVID-19 pandemic, interrupted a decade-long decline in shootings. The city has rebounded impressively, with shootings now reduced by 42% in just three years

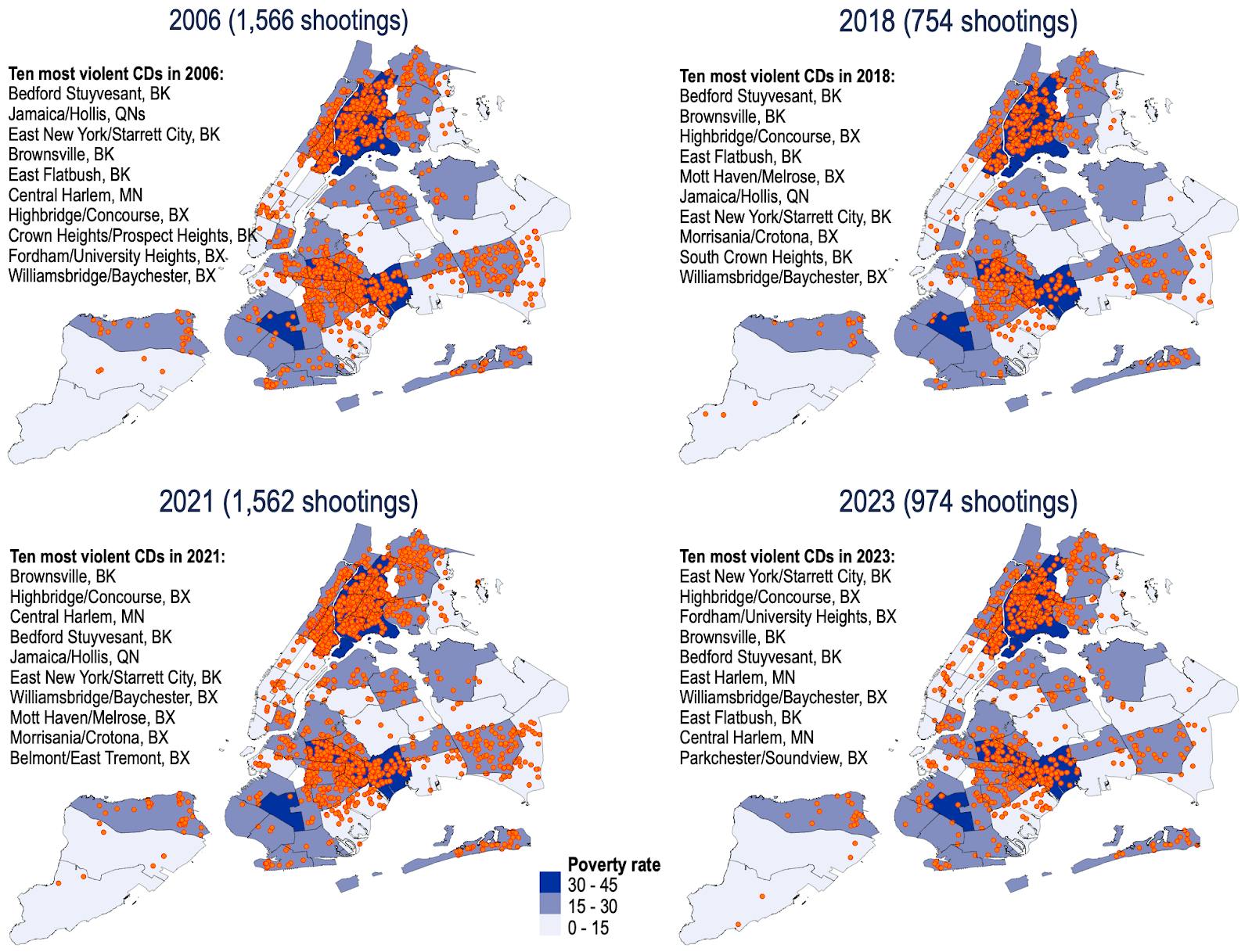

Despite the decline in overall numbers, one aspect of gun violence is unlikely to change in 2025: its spatial concentration. Year after year, a small set of neighborhoods accounts for a disproportionately large share of the city’s shootings. The line on the chart below shows the total number of shootings in New York City from 2006 to Dec. 29, 2024. Notable years include the 1,566 shootings in 2006, the first year for which geocoded shootings data are available; 2018, when shootings reached a low of 754; 2021, when they surged again to 1,562; and 2023, when they fell back down to 974.

The bars on the chart capture the enduring geographic concentration of violence from 2006 to 2023 (geocoded data for 2024 are not yet available for the full year): Regardless of the overall totals, each year, approximately half of all shootings occur in just 10 of the city’s 59 community districts. This pattern reflects a well-documented trend in cities across the United States: Violence remains tightly concentrated within a small number of neighborhoods, often the same ones year after year. Studies have shown that even within these neighborhoods, violence clusters further — limited to a narrow set of intersections and city blocks. An analysis of four years of data by Gothamist found that “just 4% of New York City’s 120,000 blocks account for nearly all of the city’s shootings.” (Remarkably similar patterns have been found in Boston.)

The spatial concentration of violence is one of the oldest insights in criminology. Early 20th century scholars like Robert Park, Ernest Burgess, Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay documented the persistent clustering of crime in Chicago. Their studies demonstrated that crime rates were closely tied to neighborhood conditions rather than the characteristics of the individuals who lived there. Despite changes in the racial and ethnic composition of neighborhoods over time, the most violent areas in one decade often remained the most violent in the next.

One structural attribute that correlates with violence is poverty. (This is not to say that poverty simply causes violence, as the relationship between economic well-being and crime is complex.) In New York City today, shootings are overwhelmingly concentrated in neighborhoods with the highest poverty rates. The maps below depict the distribution of shootings alongside community area poverty rates during key years — 2006, 2018, 2021 and 2023 — highlighting the persistent overlap between economic disadvantage and gun violence. Regardless of whether violence is rising or falling citywide, its fluctuations are felt most acutely in the city’s poorest and most disadvantaged neighborhoods. Communities such as Bedford-Stuyvesant, Jamaica, Central Harlem, East New York and Brownsville, with among the city’s lowest median income, rank among the most violent in the city. The maps also highlight the stark contrast in gun violence concentration: While some neighborhoods bear a disproportionate share of the burden, others are almost entirely shielded, rarely experiencing shootings at all.

Community district poverty rates and location of shootings in 2006, 2018, 2021 and 2023

This entrenched link between disadvantage and violence has far-reaching consequences. Research shows that exposure to violence disrupts children’s education, leading to poor academic performance. The economic toll is equally severe, as business activity and entrepreneurship decline in high-crime areas, and shrinking tax revenues from middle- and upper-income households fleeing violent urban areas further limit the City’s ability to address the root causes of violence, such as improving the quality of public education for children. Communities trapped in this cycle experience compounding disadvantages, from deteriorating public spaces to weakened institutions. In many cases, the very fabric of neighborhoods changes: The learning environment of schools deteriorates, businesses relocate elsewhere, and the dominant presence of law enforcement and criminal justice institutions structures the daily routines of low-income, minority youth.

When examining these maps, some may be tempted to attribute the persistence of violence to the culture or behavior of the residents in these neighborhoods. However, this narrative is both misleading and harmful. Research consistently shows that structural conditions — such as systemic disinvestment and economic deprivation — are among the most important causes of crime, particularly property crime (the link between economic opportunity and violent crimes is more complex and less clear). Addressing these challenges requires targeted, sustained interventions that go beyond policing.

Evidence from New York City and beyond has shown that programs addressing root causes can make a meaningful difference. Youth employment initiatives, for example, have been found to reduce violence and recidivism. Beautification efforts, like cleaning up vacant lots, have been linked to improvements in public safety. Community-led violence prevention programs can also play a critical role in disrupting cycles of violence and building trust within neighborhoods. The creation of community nonprofit organizations can generate substantial reductions in violent and property crime rates.

As New York City looks ahead to 2025, the challenge is not just to continue reducing gun violence but to address the structural conditions that concentrate it in specific neighborhoods. These interventions must target the neighborhoods most affected by gun violence, not only to enhance public safety but to address the inequities in housing, economic development and education, among many others, that perpetuate it.