Two urban planners show the power of resident-led change.

While high rates of crime are often met by local governments with increased investment in law enforcement, co-designed urban vitality can broaden the frame of public safety and support the social cohesion that decades of research have linked to sustained safety. Ask those most affected by these issues, residents of all ages, how to improve their neighborhoods right now, and citizen designers emerge full of innovative ideas where improved public spaces repair community ties and connect residents to opportunity. As urban planners and activists working at the intersection of city policy and civic engagement, we have seen firsthand the power of participatory design to reshape not just residents’ perspectives on the space around them, but also their relationships with neighbors and their agency within the systems that have historically failed them.

About MAP

Launched in 2015, the Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety (MAP) is a strategy to increase safety and well-being in 15 public housing developments in New York City through investments in improved housing conditions and public spaces, education, youth development and other community-strengthening activities. Conceived by the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice and implemented with the help of the Center for Court Innovation and dozens of neighborhood partners, MAP engages residents of public housing to identify local priorities and co-design potential solutions that are tailored to local needs. Researchers documented that MAP sites experienced declines in misdemeanors and violent crime that outpaced declines in non-MAP developments. In 2022, the city expanded MAP from 15 to 30 developments.

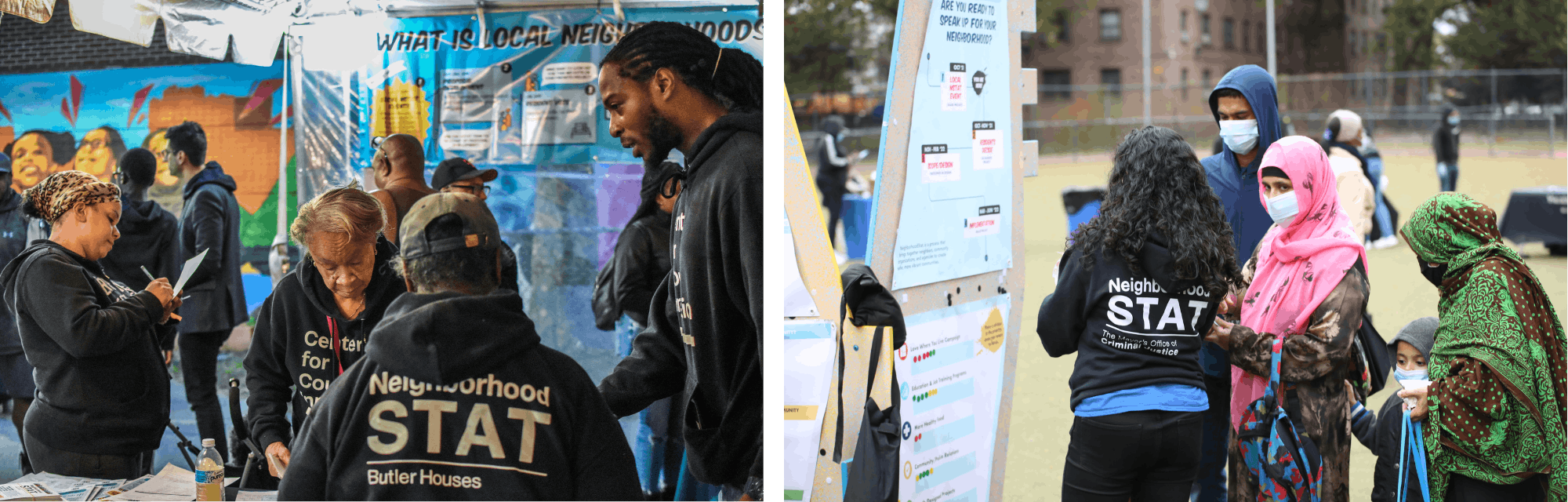

NeighborhoodStat

The foundation of MAP is NeighborhoodStat, a process inspired by CompStat, but with community leadership at the center. NeighborhoodStat engages residents, city agencies and community-based organizations to look at neighborhood-level data and resident experience to understand the underlying drivers of crime. Each of the MAP sites develops annual action plans to generate immediate improvements. The city of New York dedicates both staff and funds to turn the action plans into reality. MAP engagement coordinators employed by community organizations serve as grassroots organizers and facilitators and provide production support within a democratic decision-making process. Since 2019, more than 52 resident-designed projects have been realized.

Patterson Houses

At Patterson Houses in the Bronx, residents identified an increase in opioid addiction and danger of discarded syringes on the grounds as a problem to be addressed. In response, the NeighborhoodStat team helped clean up the areas where waste had accumulated and created community gardens as healing centers where service providers can connect with local residents. Ongoing stewardship and activations of the gardens by residents has resulted in less trash, helped connect residents to each other and increased investment from partners like New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA).

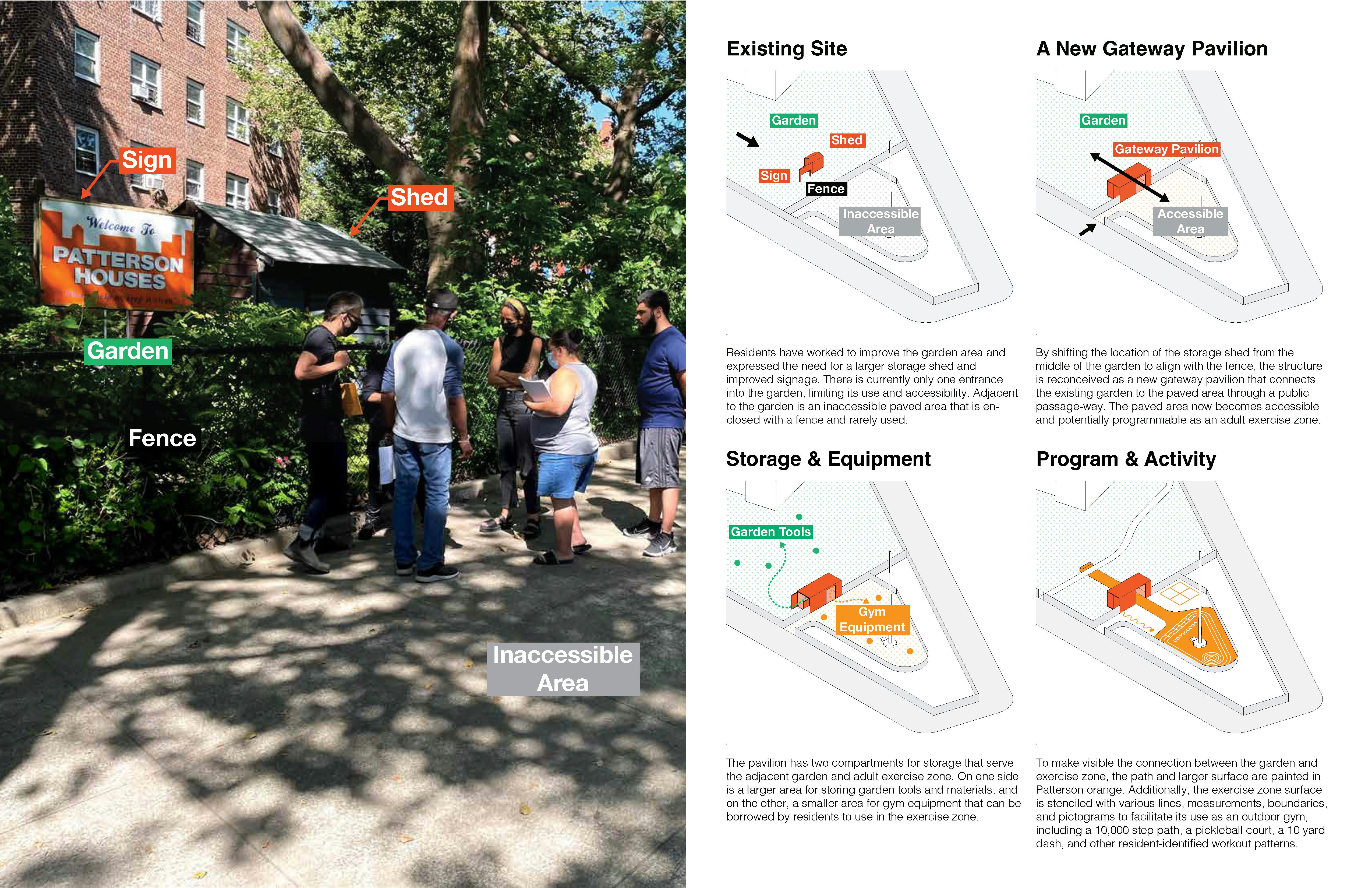

Most recently, the Patterson NeighborhoodStat team worked with Interboro Partners on The Garden Gateway project, a 1,750-square-foot intervention includes the transformation of an underutilized paved area into an adult exercise space, as well as a gateway pavilion that creates a new entry into an existing community garden and storage for exercise equipment and gardening tools. This project won the 2022 AIA Small Project Design Grant. The Garden Gateway project should be completed by winter of 2023.

Castle Hill Houses

At Castle Hill Houses in the Bronx, the NeighborhoodStat team transformed an underutilized basketball court behind the notorious “Boot” building — so named for a violent incident in the past that continued to be a magnet for antisocial activities — into Unity Park. Local residents act as stewards, activate the space through programming and maintain the cleanliness of the area.

Stapleton Houses

At Stapleton Houses in Staten Island, the NeighborhoodStat team developed a pop-up resource hub with modular, vibrant kiosks, which are permanently stored on-site in a colorful shipping container, to connect local residents to essential resources. The hub encourages more foot traffic by residents and moves them safely through the development with the help of new wayfinding signage. Residents’ regular activation of the abandoned tennis court has changed an underutilized space into a resident-driven hub that addresses isolation and the need for family support for a very youthful population with many single-kinship families.

Polo Grounds Towers

At Polo Grounds Towers in Harlem, residents transformed litter-strewn areas into spaces that accommodate positive community uses. Residents identified repeated incidents of garbage thrown from apartment windows as both a danger and an annoyance. Since the creation of this garden and sitting area, both residents and property management have reported a decrease in antisocial activity in the area and less garbage being thrown out of windows.

Brownsville and Van Dyke Houses

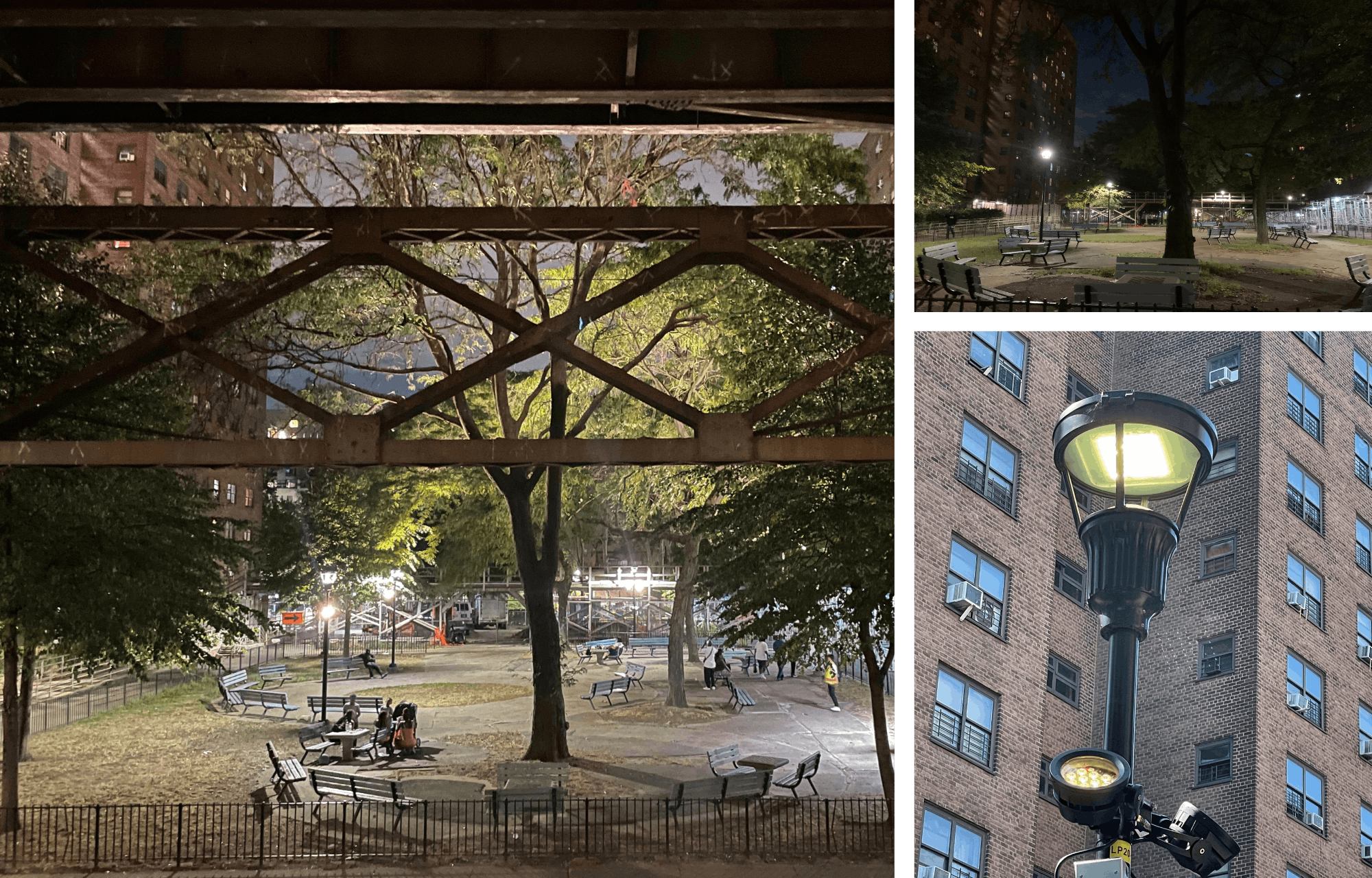

At Brownsville and Van Dyke Houses in Brooklyn, residents have complained for years about dark passages and unlit areas under the elevated train. Working with consultants from ARUP, residents developed a range of creative solutions, including the recent installation of light fixtures on existing lampposts to uplight trees and overpasses.

Brownsville Video Profile | Van Dyke Video Profile | Brownsville Policy Brief | Van Dyke Policy Brief

Wagner Houses

Resident Highlight

Sharon Cotton has lived in Wagner Houses in East Harlem for more than 50 years. She is an active participant and leader of her NeighborhoodStat team’s effort to transform a 6,650-square-foot, unsafe vacant area into an open plaza with curved pathways, seating, open lawns and a multipurpose area for holding community events. According to Cotton: “I’ve been here so long, I’m going to be honest, I’ve worked with so many agencies that said they’re going to change this, change that. ... (But) MAP made it happen. ... When (the community) realized it was residents just like them ... they come out and help us now, and they be looking for us, they call us the green shirt team. ... It's a good feeling.”

Decades of research have proven that greener, cleaner and better-utilized public spaces reduce crime and stress, support mental health and foster social connections. Over the past five years, we have witnessed the power of community-driven design to reshape neglected public spaces while critically rebuilding community trust and connection. The fallacy of “if you build it, they will come” has long been debunked, and we now know that co-design of the solution, continued resident stewardship and use of the improved space will ultimately determine the success of the design to improve safety, connect community, inspire action and sustain care of its residents.