Three examples of how working with residents to assess and redo public space can produce better city life

Public housing developments offer a unique set of public safety challenges. Concentrated poverty and other forms of disadvantage present obvious obstacles. The built environment poses its own difficulties — but may also offer some solutions.

Many public housing developments are designed as “towers in the park” — high-rise buildings surrounded by open space. Built mostly post-World War II, from 1945 to 1965, this typology was intended to liberate “slum” dwellers from dense, congested streets and to provide ample light and air and new, landscaped open space.

In reality, the closing of streets to create “superblocks” and the setback of buildings from the normal street grid meant they often felt disconnected from their surrounding neighborhoods. To make matters worse, the federal government would not fund non-residential amenities, such as retail, day care and health clinics, as New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) had done in earlier projects such as Williamsburg and Harlem River Houses. This further disconnected the “tower” projects from the urban context.

A 2017 study of the Ingersoll Houses in Brooklyn, jointly conducted by Pratt Institute and Gehl Institute, offers some valuable insights into how the problems of “tower-in-the-park” housing might be addressed through a focus on “placemaking” — a process by which public space is designed and programmed to meet social needs. The project, Public Life and Public Safety, was commissioned by New York City in the fall of 2016 to better understand the residents’ perceptions of safety and use of the grounds to inform design recommendations that would activate the grounds and promote community life. The institutes developed an ethnographic research approach that engaged residents in the public space at Ingersoll Houses.

Located in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, Ingersoll Houses comprises 20 buildings built in 1944, housing over 4,000 residents. The campus sits close to downtown Brooklyn and is surrounded by an increasingly wealthy residential population. The grounds include a significant amount of public open space. However, much of this space is not used, either because it is fenced off to prevent access or it is considered unsafe by residents. Forty-six percent of the campus is fenced. Only 6.6% is officially designated for recreational use. Much of the open space lies in an undifferentiated state where there is no clear sense of “ownership” by residents.

From extensive interviews with residents, the Gehl/Pratt study found that, while most Ingersoll residents felt that the campus was safe, there was a weak sense of community and very little social activity on the grounds.

Residents are limited to pathways, sidewalks, basketball courts, and playgrounds. They are unable to access the fenced-off grassy sections of the grounds, even though these areas make up over 40% of the total open space of the development. Understandably then, the respondents to our intercept surveys told us that they primarily use the grounds for necessary activities, such as walking through the site (59.6% of respondents). Across all demographics, few people reported using the grounds for enjoyment or leisure. When asked which elements residents use most often, the majority of respondents said sidewalks/pathways (67.8%), seating areas (37.5%), and playgrounds (35.4%). Youth used the basketball courts but otherwise do not spend their free time on the grounds.

The study made a series of recommendations to improve the social use of public space to increase residents’ sense of safety and to support an overall sense of community. The recommendations include:

- Designing improvements to the grounds, including an expanded use of fenced-off areas.

- Enhancing community networks and increasing residents’ control over decision-making.

- Developing programming that serves residents’ needs.

- Integrating the housing development into the neighborhood fabric by the design treatment of entrances.

In Ingersoll, residents are most likely to know other residents in their building and to see them as they enter and leave. However, the public areas immediately outside the building entrances are rarely used for social interaction. While benches are provided, the design of those areas is inflexible, and activities such as barbecuing that would generate social interaction are not permitted by management.

There are many signs posted on the grounds telling residents what they cannot do, but none that encourage the kind of social activities that would help deter crime. One proposed design solution was to create social spaces in front of the building entrances that would make it comfortable for residents to hang out, barbecue and socialize. Residents of the building could take ownership of the public space and make it work for them.

While the current design of building entrances does little to promote a sense of place and connectedness, the community garden at Ingersoll is a focus of social life and provides a unique opportunity for cultural exchange between the Asian and Hispanic residents around the growing of different plants for cooking. In some ways, the community garden exemplifies, on a small scale, how an inviting, shared public space can make a positive contribution for the residents.

Apart from adding natural beauty to the grounds, the garden brings together residents of varying age, race and gender. Additionally, the garden is an amenity that is reserved for residents; they have full ownership over the space and indeed organize meetings and events related to the garden. The garden has been successful in promoting resident engagement. The growing of different vegetables helps bridge language and cultural barriers between the Chinese-speaking residents and other residents. Further, through the community garden, residents have the ability to create and reinforce their own rules. There is a collective respect for the community garden, which reduces the likelihood of theft and destruction. In these ways, the garden is an example of informal social control in action.

Despite the demonstrable success of the community garden, residents’ request for increased community garden space had not been met at the time of the Gehl/Pratt study.

The study also looked at the nature of entrances to, and pathways through, the development. Residents found entrances and pathways anonymous and ill-defined, and they felt little sense of ownership and identity. Small design interventions such as porticos with signage identifying the development could help provide a greater sense of place and give residents a sense of “ownership” over the public pathways through the development.

Following the study, NYCHA made very few changes, indicating the inertia that must be overcome in the management of public space. Arguably, some proposals would increase the maintenance burden on management (e.g., allowing barbecuing at building entrances), but there appears to be little enthusiasm within NYCHA management to consider the social benefits of these changes to residents.

Of course, Ingersoll is far from the only NYCHA development that could benefit from thoughtful placemaking. In the Bronx, NYCHA has sought to use socially informed design to improve public safety and promote social cohesion as part of its Morrisania Air Rights (MAR) development.

MAR, straddling the Metro-North rail tracks, was a triumph of civil engineering when it was designed in the 1970s, but not exactly a model for social housing design. The building entrances were deep into the structure and flanked by thick concrete fins that helped to support the structure above while obstructing sight lines. As a result, there was no possibility of “eyes on the street” at the entrances, and security was a persistent problem. Doors were frequently broken and vandalism was prevalent. Tenant patrols — residents providing their own form of security and watch over the building entrances and public spaces — were not a viable option because there was no place for people to sit.

The design solution was to move the entrances out to the street line and to provide space for the tenant patrol to sit and monitor entry to the buildings. Residents sit in the room that oversees the entrance and can monitor anyone who goes in and out of the building. Young residents of the building were invited to design wall tiles that were incorporated into the lobby walls, giving them a sense of ownership of the public spaces. Thus, design was able to support a management solution to enhancing resident engagement and improving building security.

It is no accident that the Morrisania Air Rights project took special pains to incorporate young residents.

A recent project, sponsored by the AIA Center for Architecture and presented as part of the exhibition “Reset: Towards a New Commons,” looked at three NYCHA developments in Harlem through the eyes of young residents, asking them to reflect on how they would use public space in their community.

You forget about the moments and what you have right in front of you. It’s about building memories with those who you care and love and hold closest to you and cherish the most, you know?

Devvon Howell, NYCHA resident

The project was an exercise in participatory design, engaging young people from three neighboring NYCHA developments with a history of conflict. The project asked how public play could shift the way we relate to one another in our common space. Moving at the speed of trust over a period of six months, engagement was a collective act of working with, not “on” or “for” the community. The process strengthened the bonds among the young people from each of the three NYCHA projects, an outcome that was as important to establishing the commons as the development of any physical designs.

For example, young resident designer Aboubaker Cherry envisioned a “yellow brick road” for the Thomas Jefferson Houses, and sought to enliven community spaces with color, nature and culturally relevant designs. And Brendon Valerio, another young resident designer, created a multimedia collage that transformed the entrance courtyard of the Johnson Community Center into a gathering place that would be more welcoming for local residents.

“These places look dark and dim and you can see the struggle in it. … If it were brighter, with more things going on in the community to keep people busy, you could get more people involved. …Things like this can happen. When people lose hope, they will lose their mind."

Aboubaker Cherry, Thomas Jefferson Houses

The enthusiasm released among these young designers by the process of engagement is inspiring. They transitioned from feeling disempowered and excluded from decision-making to creatively invested in their public space. One lesson from this study, however, is that these processes take time and effort — elements so often lacking in the urgent call to “fight crime.”

What are some of the basic ways we can encourage communities to “own” their public space and ensure the civic pride that deters street crime? A 2018 study by the Center for Active Design found several answers. By asking respondents what would make them feel more civic pride in their neighborhood and more likely to participate, they found four main influencers.

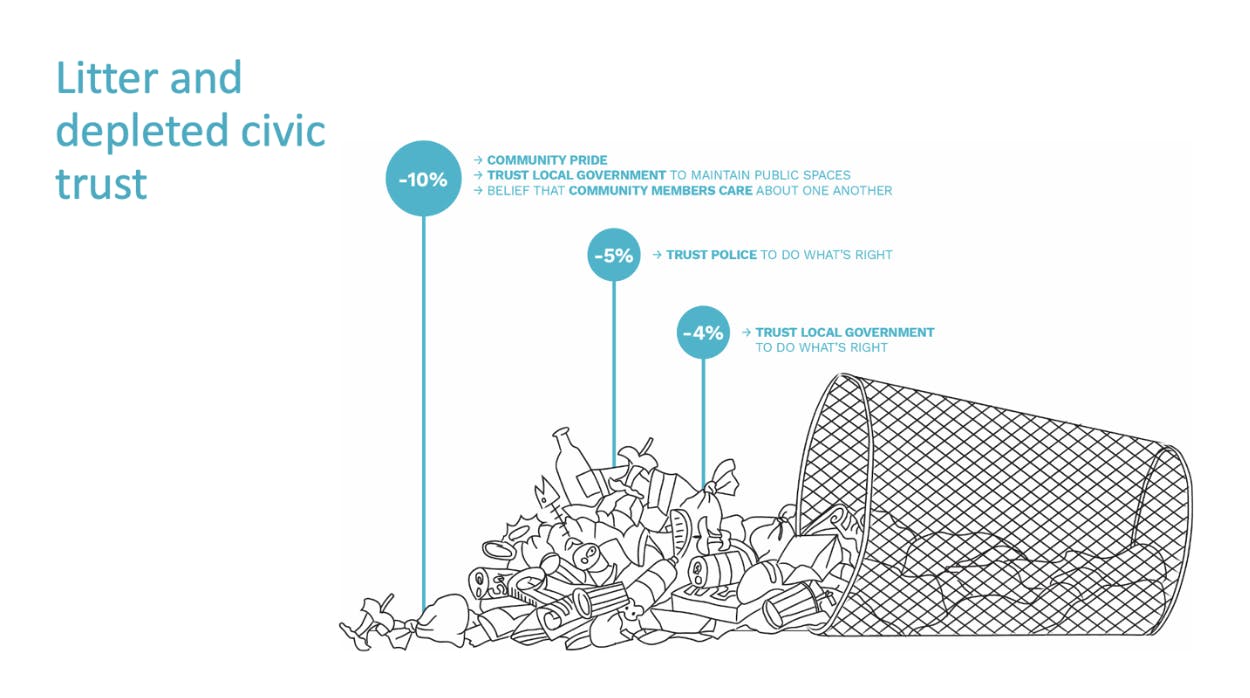

Litter and depleted civic trust

The first, perhaps not surprisingly, was the impact of litter. People who say litter is very common in their neighborhood exhibit lower levels of civic trust — scoring 10% lower on questions about community pride and trust in local government.

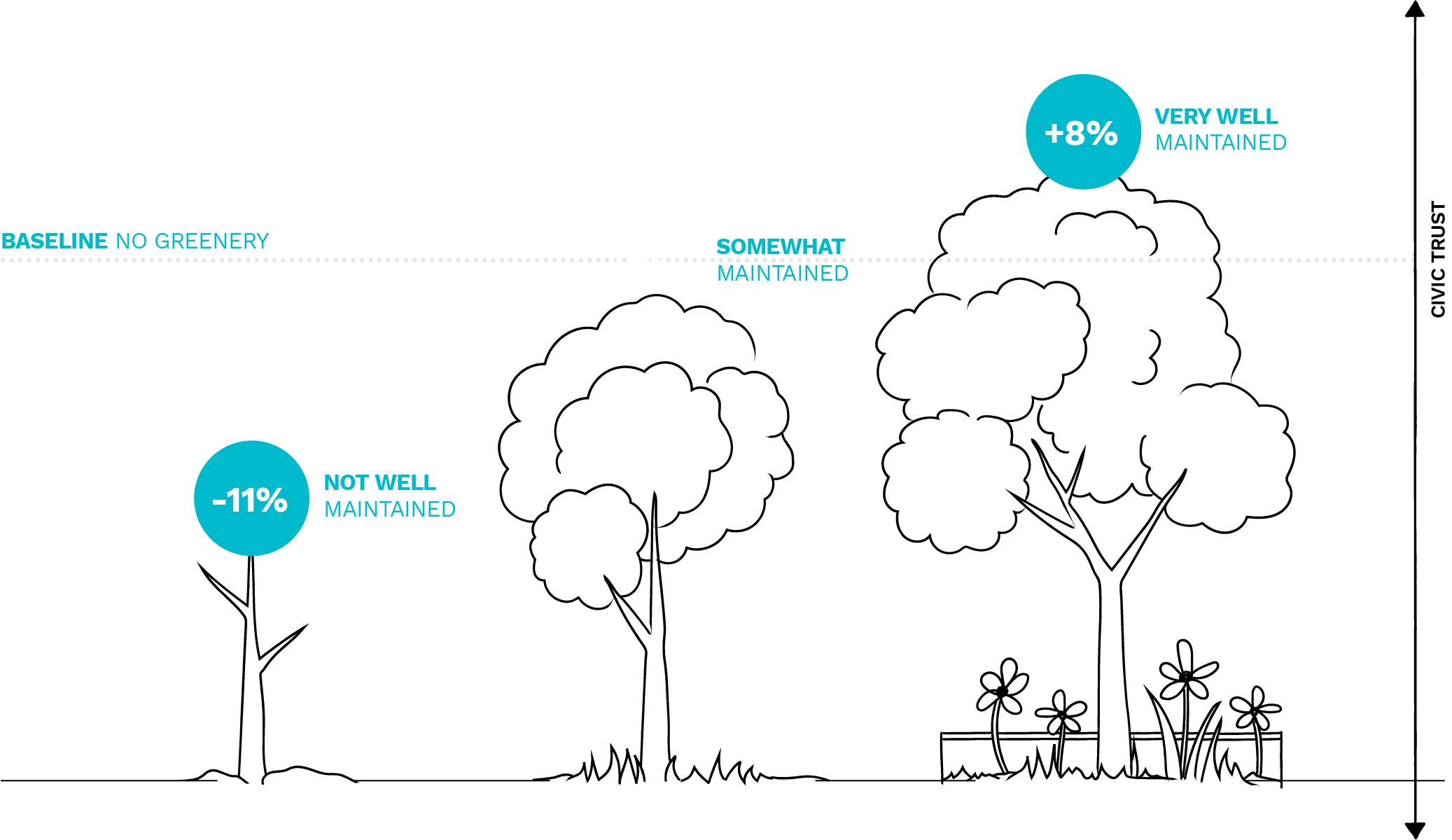

Public greenery

On the positive side, people who have well-maintained greenery on their block have significantly higher levels of civic trust while people with poorly maintained greenery exhibit lower civic trust outcomes than those with no greenery at all.

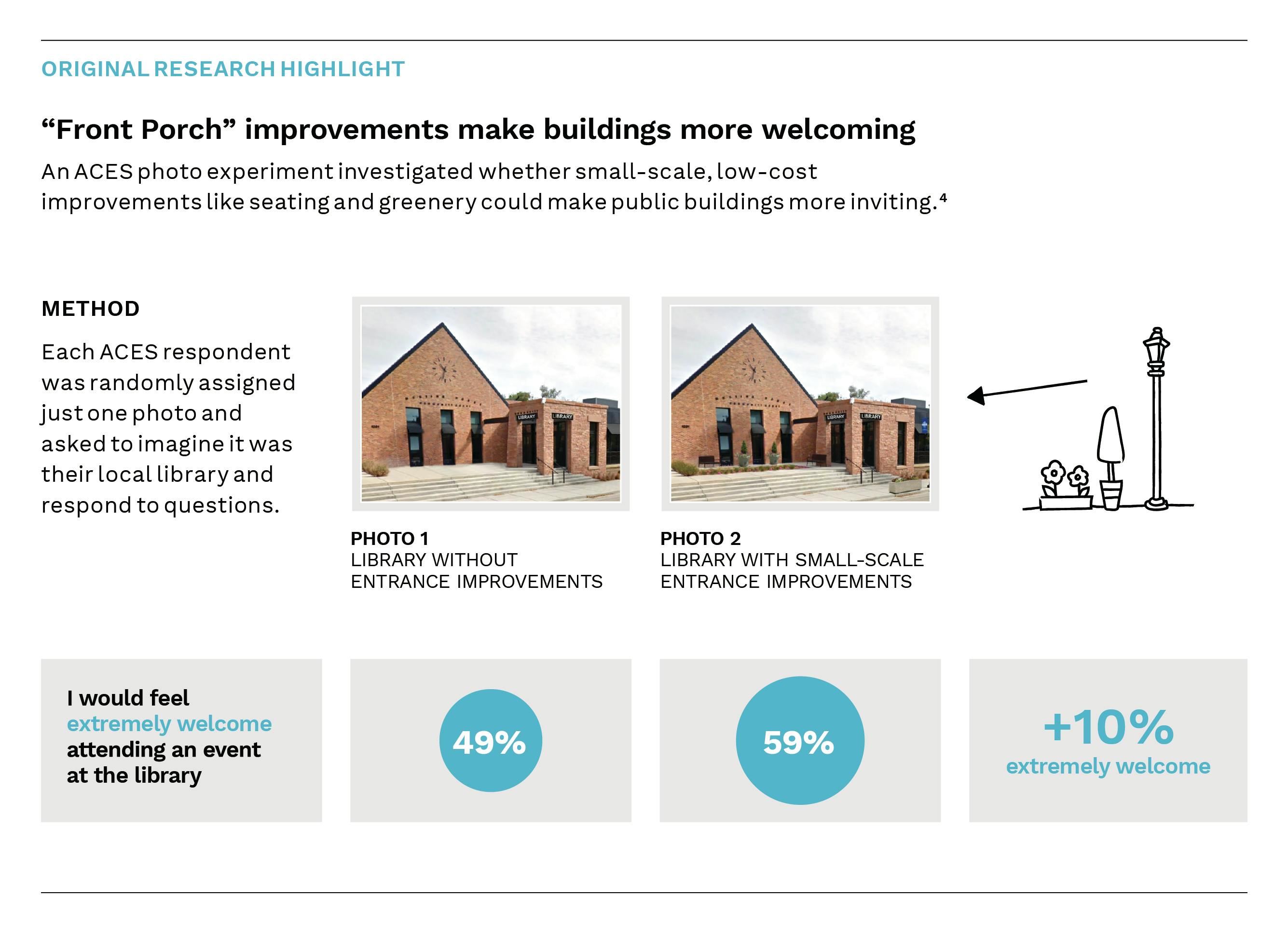

"Front porch" improvements

Small-scale, low-cost improvements can make a public building feel more welcoming.

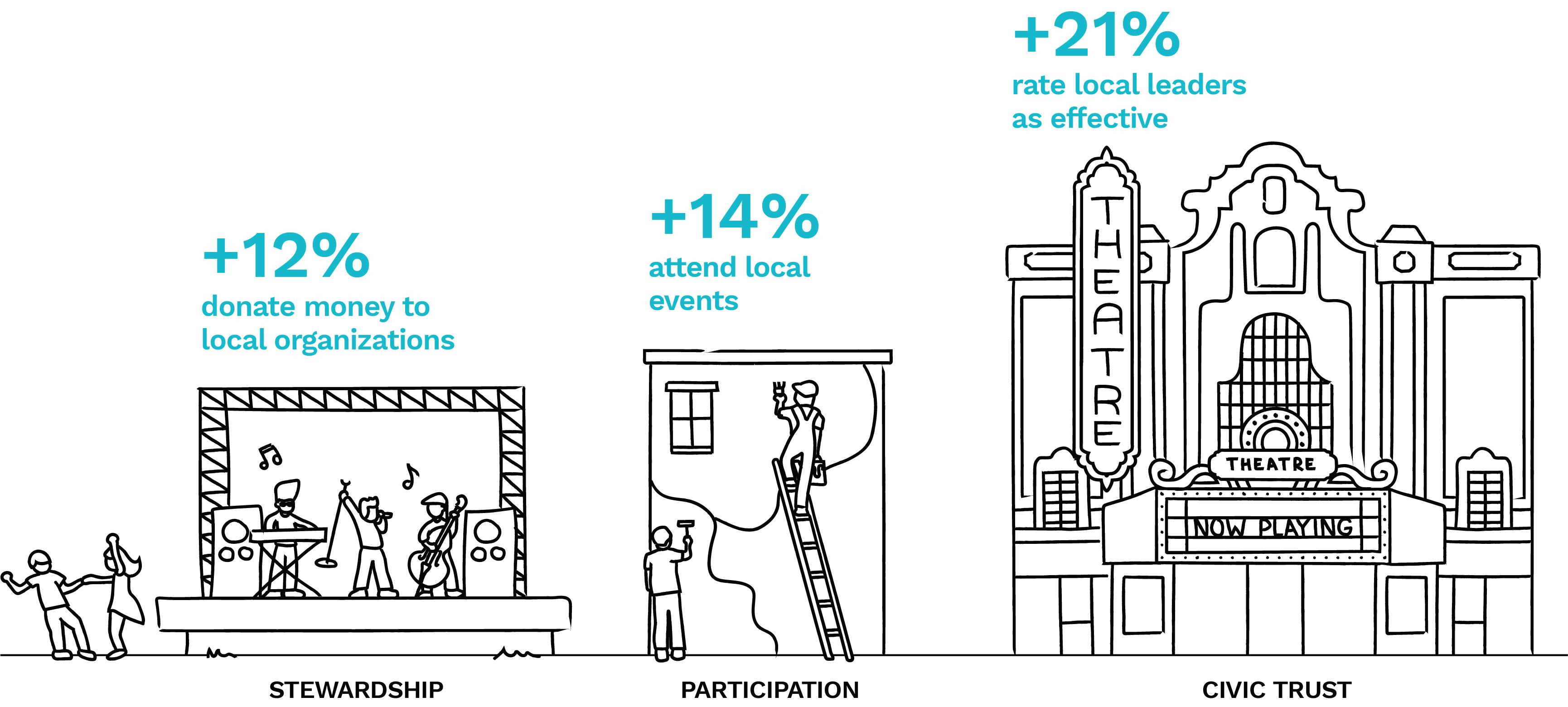

Arts and culture

People who report high levels of access to arts and culture also score higher on civic life outcomes — they’re 21% more likely to rate local leaders as effective.

So perhaps when we think about where to spend our tax dollars on public safety, we might consider these measures. What mayor wouldn’t want to see a 21% improvement in the rating of local leaders as effective — just in return for improving access to arts and culture.

Public space is too often designed and built with little reference to the social needs of those who actually use it. Public housing in particular was designed and built with no available data on user needs. And of course over the time, the demographics of the residents has changed significantly, as have their social needs.

The example of MAR shows the level of effort that can be required to analyze the use of public space and then develop appropriate design solutions. Furthermore, these design solutions are not everlasting. It can be no surprise that designs created 50 years ago are not so relevant today. So there must be a continual revisiting and reevaluation of public spaces to ensure they are working socially for today’s users.

This takes time and effort. Sometimes conflicting interests in the use of space (e.g., seniors versus youth) can complicate design solutions. But we have seen consistently that design without social analysis is seldom successful. Similarly, programming and management of space needs to be continually informed by social research. Too often, programming and management falls into a routine, often based on minimizing maintenance needs, that does not serve the users. This too takes time and effort.