Expand the reach of the subways by meeting riders where they are.

Introduction

Most of New York’s peers — London, Paris, Beijing, even Los Angeles — are expanding their rapid transit networks at a frenetic pace. New York is not. The system has scarcely expanded since the City took over the old private subway companies in 1940. In fact, the system has shrunk in many places. The elevated lines on Ninth, Sixth, Third and Second Avenues are long gone, as are the Fifth, Myrtle and Lexington Avenue Elevated Lines in Brooklyn, and there are no trains on the Brooklyn Bridge anymore.

Things don’t have to be like this. Before the Second World War, New York built subways in bulk, just like New York’s peers do today. The first subway, running eight and a half miles from Harlem to City Hall, took only four years to build, start to finish. As such, this series of maps is meant to be a vision of what the subway could look like if New York decided to emulate London, Paris, Beijing and LA.

In designing these extensions, I’ve made three major assumptions. First: The various transit agencies of the Tri-State Area can stop bickering and agree to free transfers and through service. Madrid has a good model for this, which can be emulated in New York. Like in New York, Madrid’s subways, city buses, suburban buses and commuter trains are all run by different agencies, but they share fare zones and tickets.

Second, I’ve assumed major organizational reforms to the commuter rail agencies to allow the commuter rail lines to do double duty as superexpress subways, as they do in Madrid, Paris and Tokyo. Paris’s RER and Madrid’s Cercanías run trains every 15 minutes or less, all day, as do most of Tokyo’s commuter rail lines. This would not be impossible for New York to do — but it requires a lot of bureaucratic wrangling to get the most efficiencies possible out of the existing system.

Most of the changes New York needs are organizational, like free transfers between the commuter lines within the city limits, and staffing changes, like one-person train crews. Other modifications require some capital investment, like ticket machines and turnstiles at commuter rail stations, and compatible equipment so that trains from Long Island or Westchester can run through to New Jersey and vice versa.

Third, I’ve grounded the new lines shown on the map in sound transport planning. The new T and X trains follow some of New York City’s busiest bus routes, as do the extensions of the 2, 4 and 5 trains. Similarly, the tunnel between Grand Central, Penn Station and Hoboken is meant to reduce overcrowding on the crosstown E train, in addition to making a commute from, for example, Westchester to Jersey City much more practical.

Better regional integration

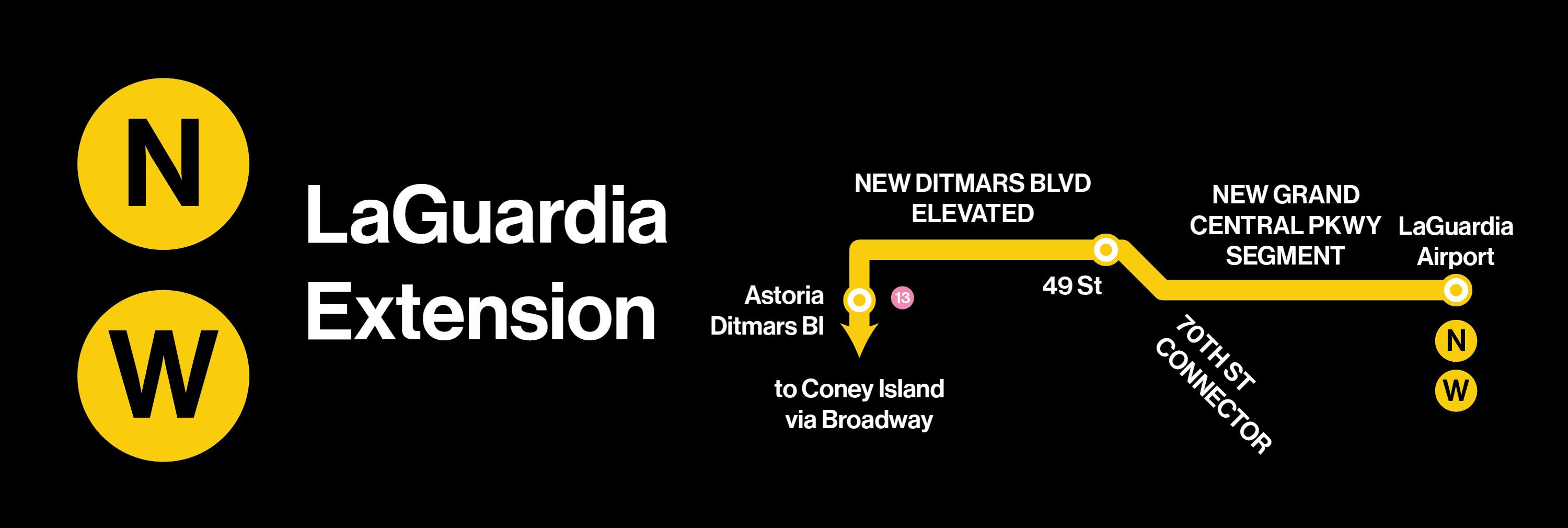

N/W: LaGuardia Airport extension

LaGuardia Airport is the only major airport in the Northeast not served by rail. Plans to serve it have been poorly planned, like the so-called “backwards Airtrain” from the administration of former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, or the ill-fated attempt to extend the N train to the airport under Mayor Bloomberg. This project would extend the N/W trains to LaGuardia via Ditmars Boulevard and the Grand Central Parkway, with an intermediate stop at 49th Street, serving a subway desert and providing a quick connection to Manhattan.

Y/8: Integration of the PATH Sixth Avenue lines into the subway system, and extension to Newark Airport

A simple way to improve regional integration is to remove unnecessary barriers, like extra fares. This part of the proposal involves integrating the PATH trains into the subway system, with free transfers. This requires administrative and rebranding changes, but little in the way of heavy construction. The World Trade Center services I’ve relabeled as the 8 train; the PATH services on Sixth Avenue I’ve relabeled as the Y train.

In addition, this plan involves connecting PATH to Newark Airport.

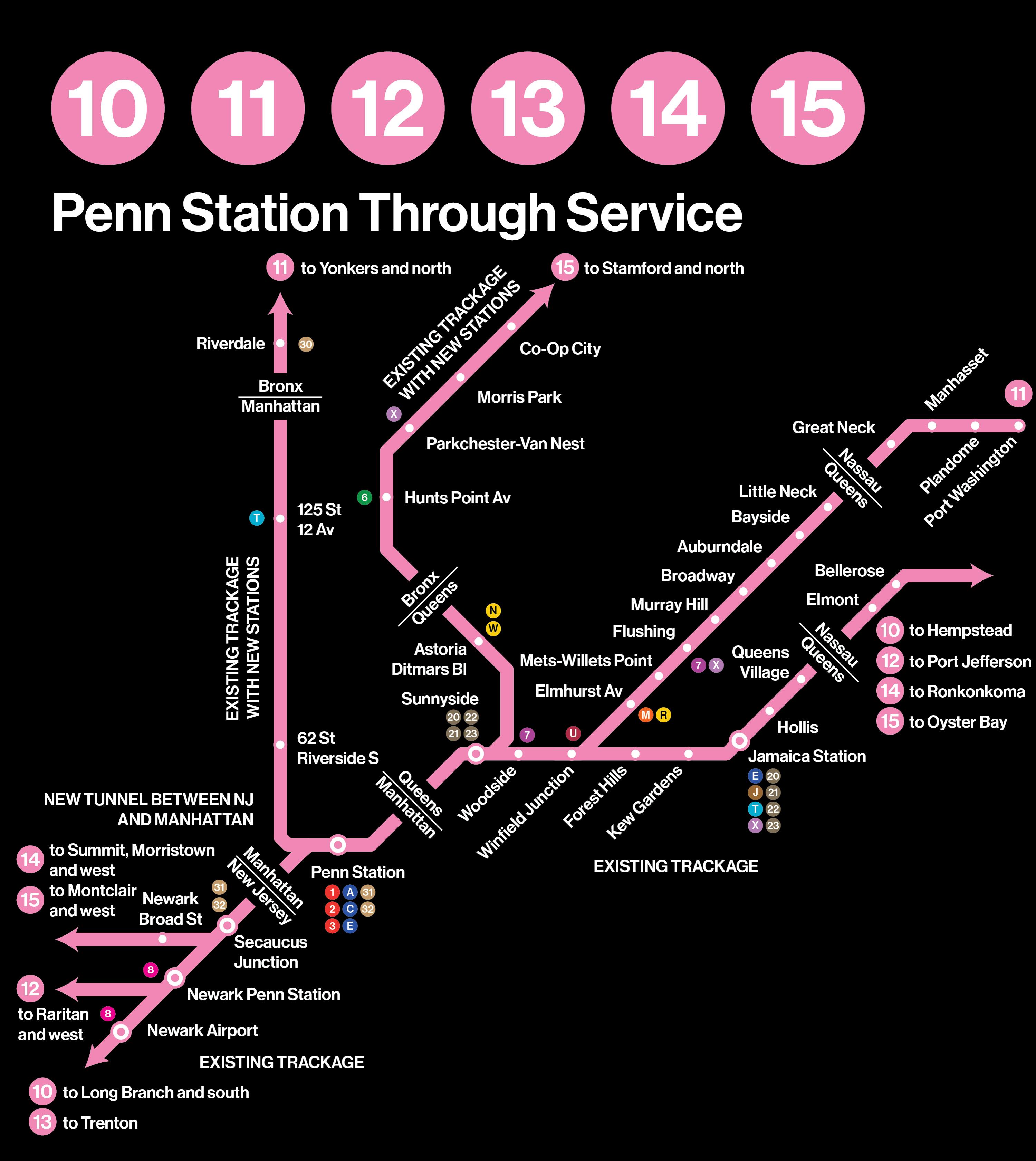

10/11/12/13/14/15: Through service through Penn Station connecting Metro-North, the Long Island Rail Road and New Jersey Transit

The centerpiece of modernizing the commuter rail lines into the subway is through-running at Penn Station. That is, trains entering Penn Station from one side would exit on the other side, rather than all trains terminating at the station. (This is a proposal described by ReThink Studio and many others over the years.)

This proposal would require significant modifications to the regional rail network in addition to the bureaucratic reforms necessary to make through running possible. Not only is an extra tunnel under the Hudson necessary, as proposed by the Gateway Project, the widening of the approach track from Metro-North’s Hudson Line to two tracks, and standardizing Metro-North, LIRR and NJ Transit electrification equipment. The end result, however, is a layer of superexpress subways. For instance, from Midtown West to Flushing on the 7 train today is 32 minutes on the express and 41 minutes on the local. It’s only 21 minutes by LIRR today, but the LIRR is more expensive and service is far less frequent than the subway. Both of these things can be fixed with free transfers and more frequent service.

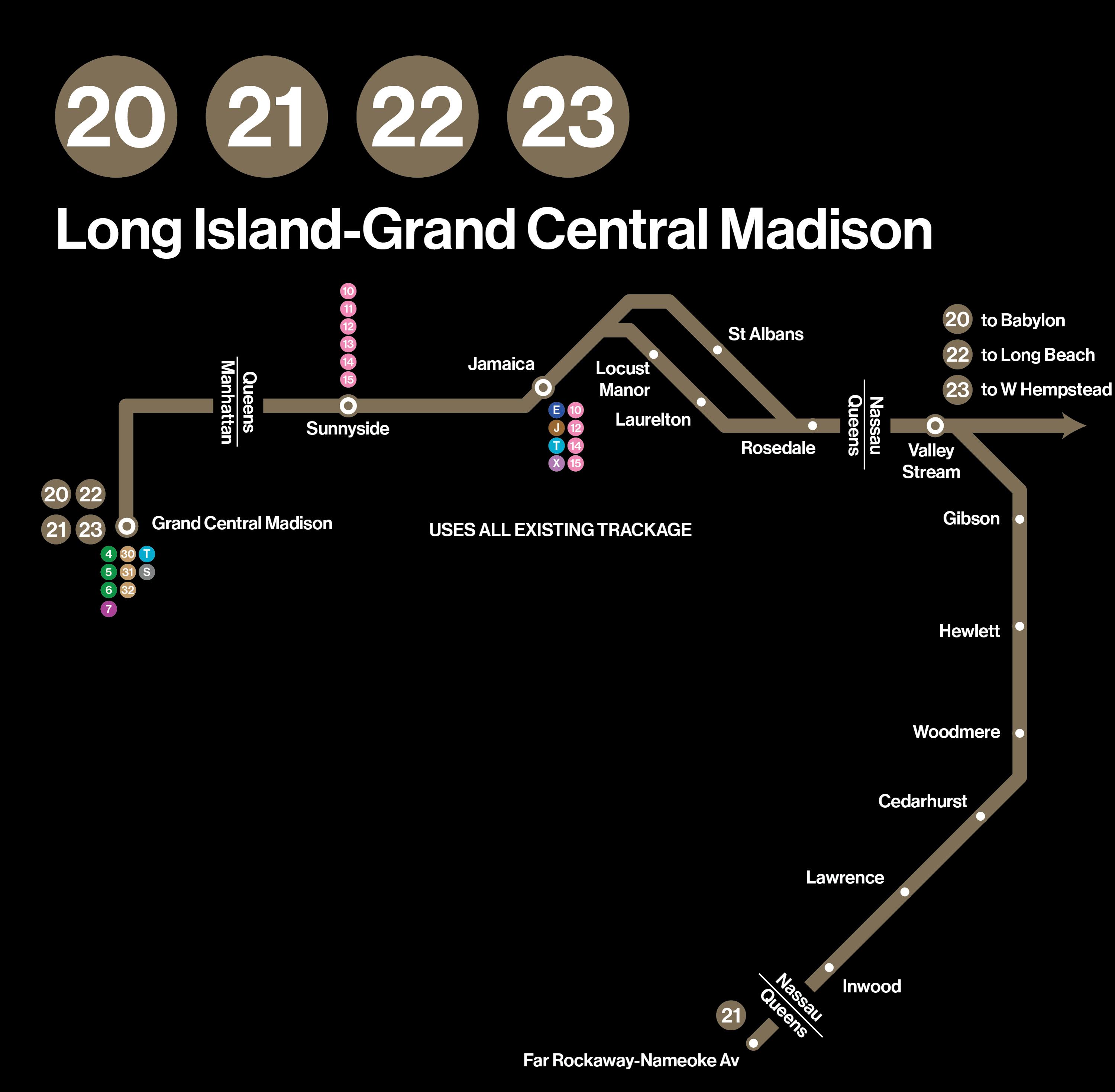

20/21/22/23: Integration of the LIRR lines to Grand Central into the subway

The same process would happen with the LIRR lines that run into Grand Central Madison, with one simplification: LIRR lines running to the South Shore of Long Island run to Grand Central, with LIRR lines from the North Shore running through Penn.

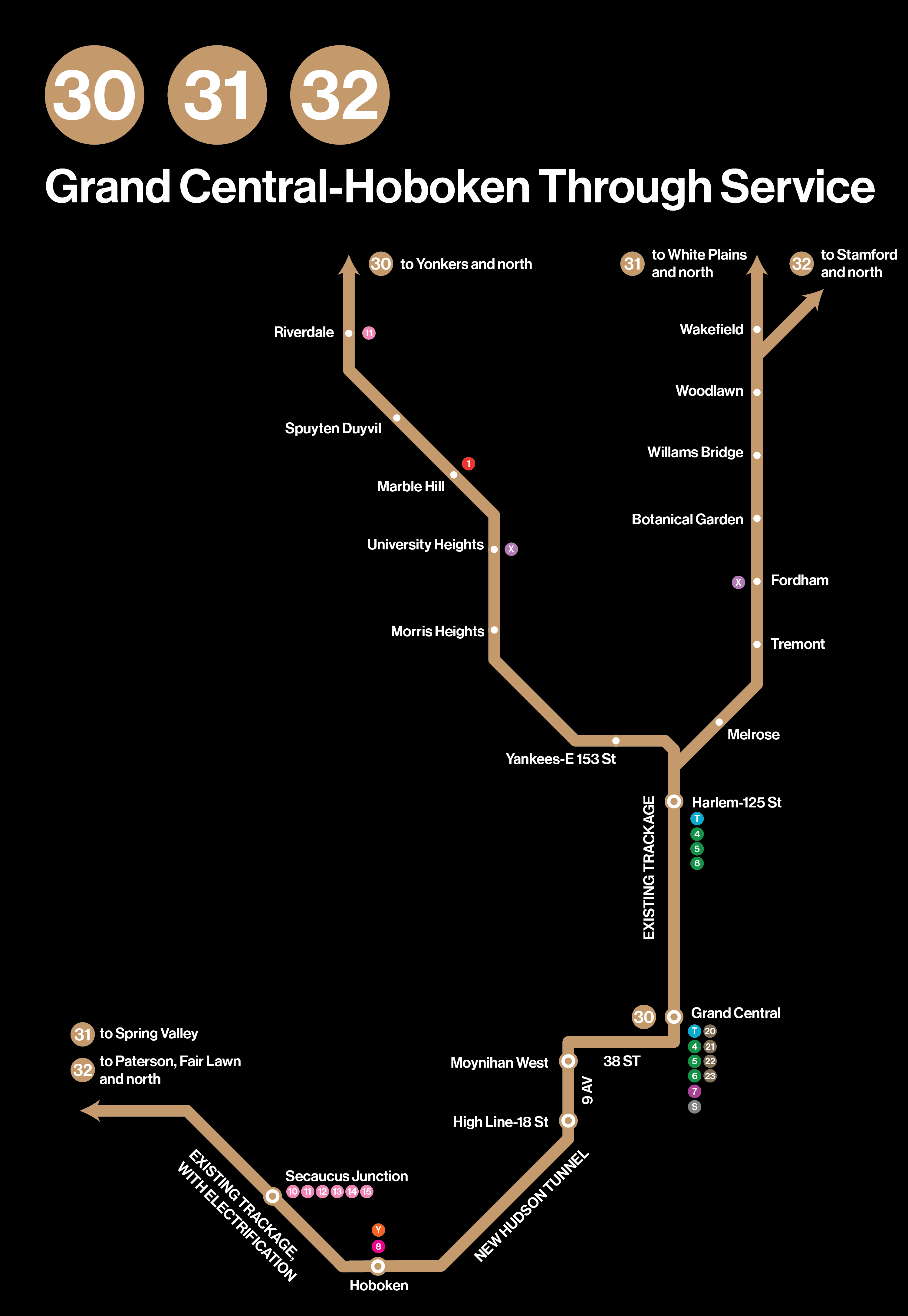

30/31/32: Integration of Metro-North into the subway and Grand Central-Penn tunnel

In addition to the reforms noted above, another logical track would be to build a tunnel between the dead-end stations at Grand Central and Hoboken. This tunnel would continue downtown from the lower deck of Grand Central via Madison Avenue, 38th Street and 9th Avenue-Gansevoort Street, and from there underneath the Hudson to Hoboken and beyond, with intermediate stops at Moynihan West (9th Avenue and 33rd Street) and the High Line (18th Street and 9 Avenue). The Pascack Valley, Bergen and Main Lines would be electrified and serve as the western half of the route.

New crosstown service

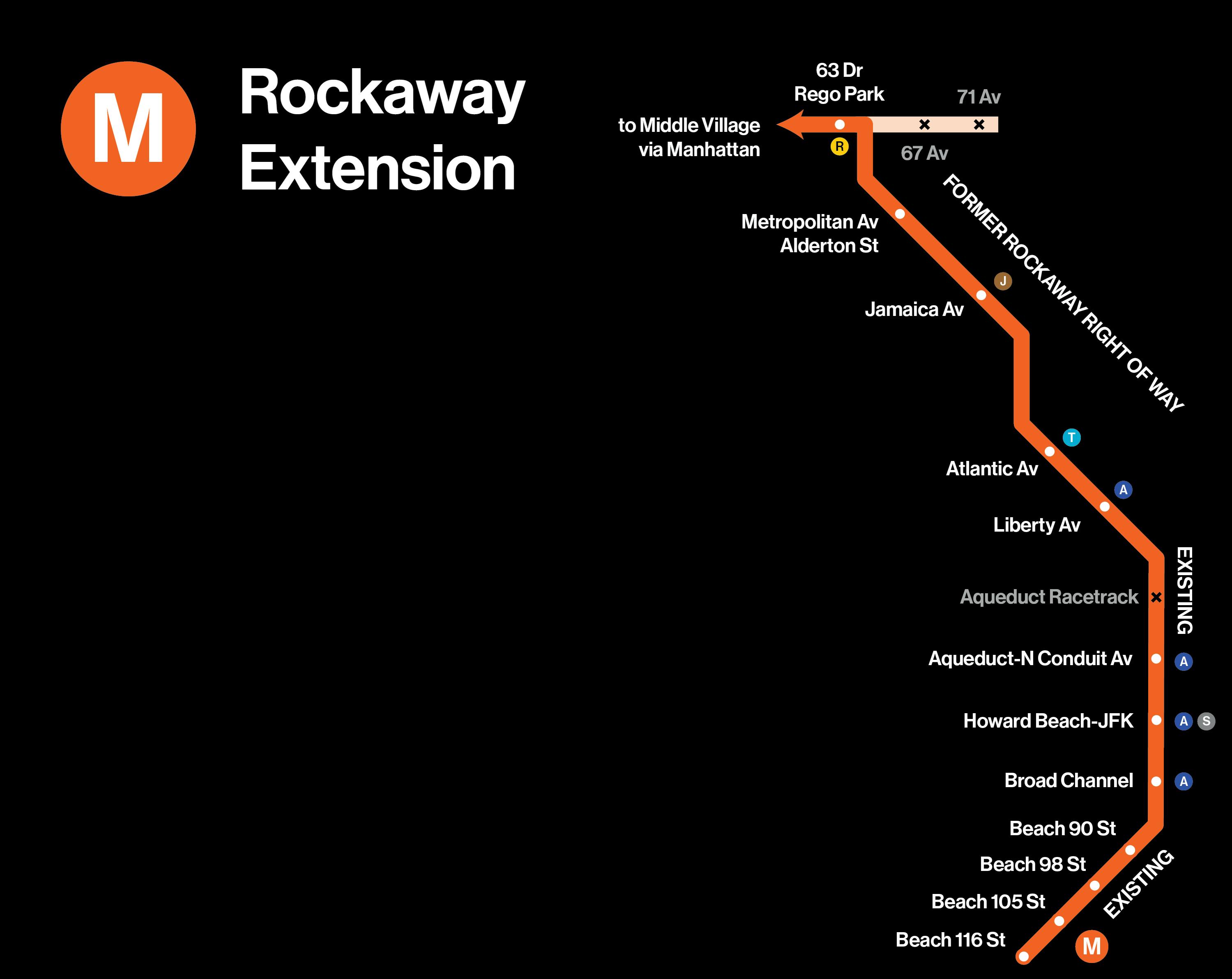

M: Rockaways extension

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Long Island Rail Road ran commuter service to the Rockaways using an elevated structure from Rego Park, running parallel to Alderton Street, through Forest Park, then running parallel to 98th and 100th Streets as far as Liberty Avenue, then onto the route used by the A train today to reach the Rockaways. This structure has been abandoned since 1962. But the MTA still owns the structure and the underlying land. Reactivating it and connecting it to the Queens Boulevard line would be relatively straightforward, as the Queens Boulevard local tracks have unused tunnels that were designed to make such a connection possible. All it would require is a short, one-third-mile tunnel, as proposed by the QueensLink project.

With this connection, the M train would replace the Rockaway Shuttle, providing vital crosstown connections in an area of Queens that currently directs all subway service to and from Manhattan.

As part of this project, the Aqueduct Racetrack station in Queens would be closed. Aqueduct Racetrack is one of the subway system’s least-used stations, designed for an era when horse racing was still a major sport. Formerly open only on racing days, the station is duplicative. Aqueduct-North Conduit Station, which has both uptown and downtown platforms, is only 300 yards to the south, at the opposite end of the racetrack’s parking lot.

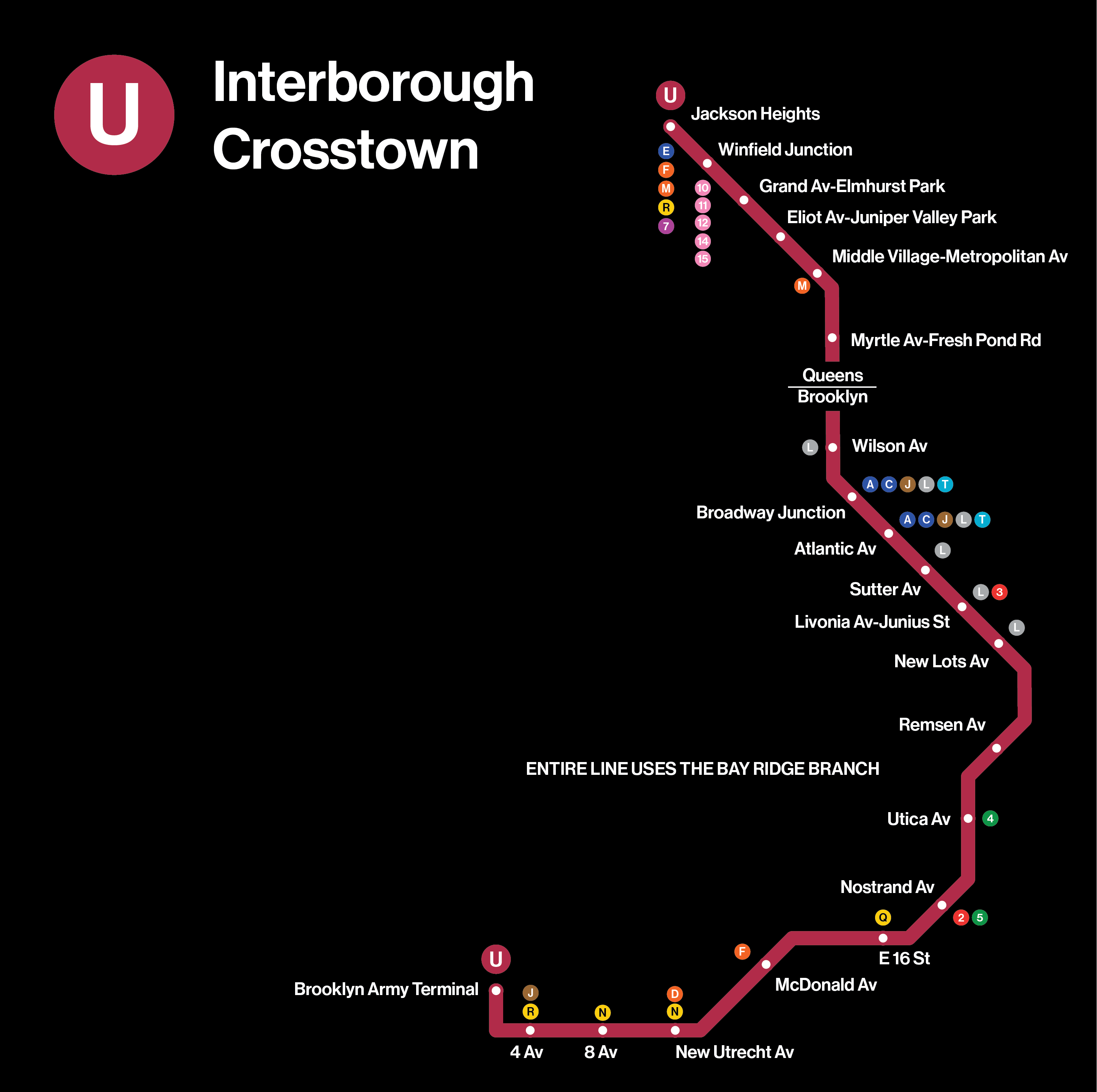

U: Brooklyn-Queens outer crosstown line

The U train is a variant on the Interborough Express proposed by Gov. Kathy Hochul. Ideally, the Interborough Express would be converted to use subway trains, and fully grade-separated from other traffic (i.e., no intersections). The one station addition proposed here to the governor’s plan is to reopen the Winfield Junction station at 73rd Place and 51st Avenue in Maspeth, providing a transfer between the services using the LIRR Main Line and the U train. This line also parallels portions of the B6 and Q58, the second- and third-most-used bus lines in the city, respectively.

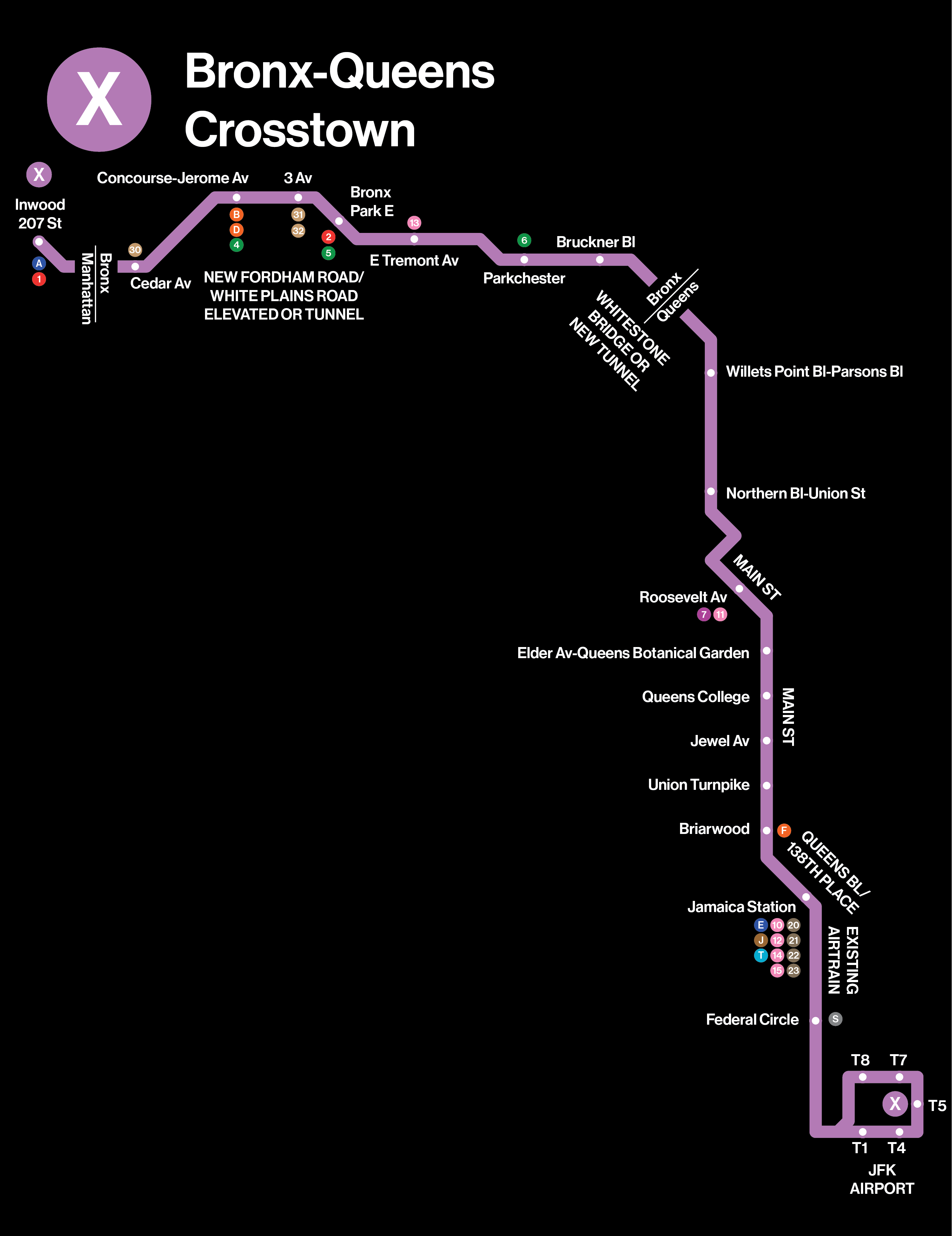

X: Bronx-Queens crosstown line

The X train shown here is a Queens-Bronx crosstown line that combines two of the busiest bus lines in the city with an underused rapid transit line. The X train grafts together the Bronx’s crosstown Bx12, the busiest bus line in the Bronx and fourth-busiest citywide); the Q44, the third-busiest bus line in Queens and 10th citywide; and the underutilized JFK AirTrain. The AirTrain uses the same subway technology used in Vancouver’s SkyTrain; it is fully capable of providing subway-style service.

The current AirTrain terminal at Jamaica would be moved to an elevated station at 138th Place over the Jamaica railyard, then continue to Flushing via 138th Place, Queens Boulevard and Main Street, serving Kew Gardens Hills, Queens College and the Queens Botanical Garden. From Flushing, it would proceed north, elevated over Northern Boulevard and Union Street, crossing between the Bronx and Queens using either the Whitestone Bridge or a new tunnel. Once in the Bronx, the route would run crosstown, via the Cross-Bronx Expressway, White Plains Road and Fordham Road, ultimately terminating at a new station on West 207th Street, in Inwood.

Using an AirTrain extension allows elevated structures and stations to be built smaller and less intrusive than the big, noisy steel elevated lines seen on the J, M and 4 trains. As noted previously, this conversion requires the Port Authority to share tickets with the subway, with free transfers.

Modernizing existing routes

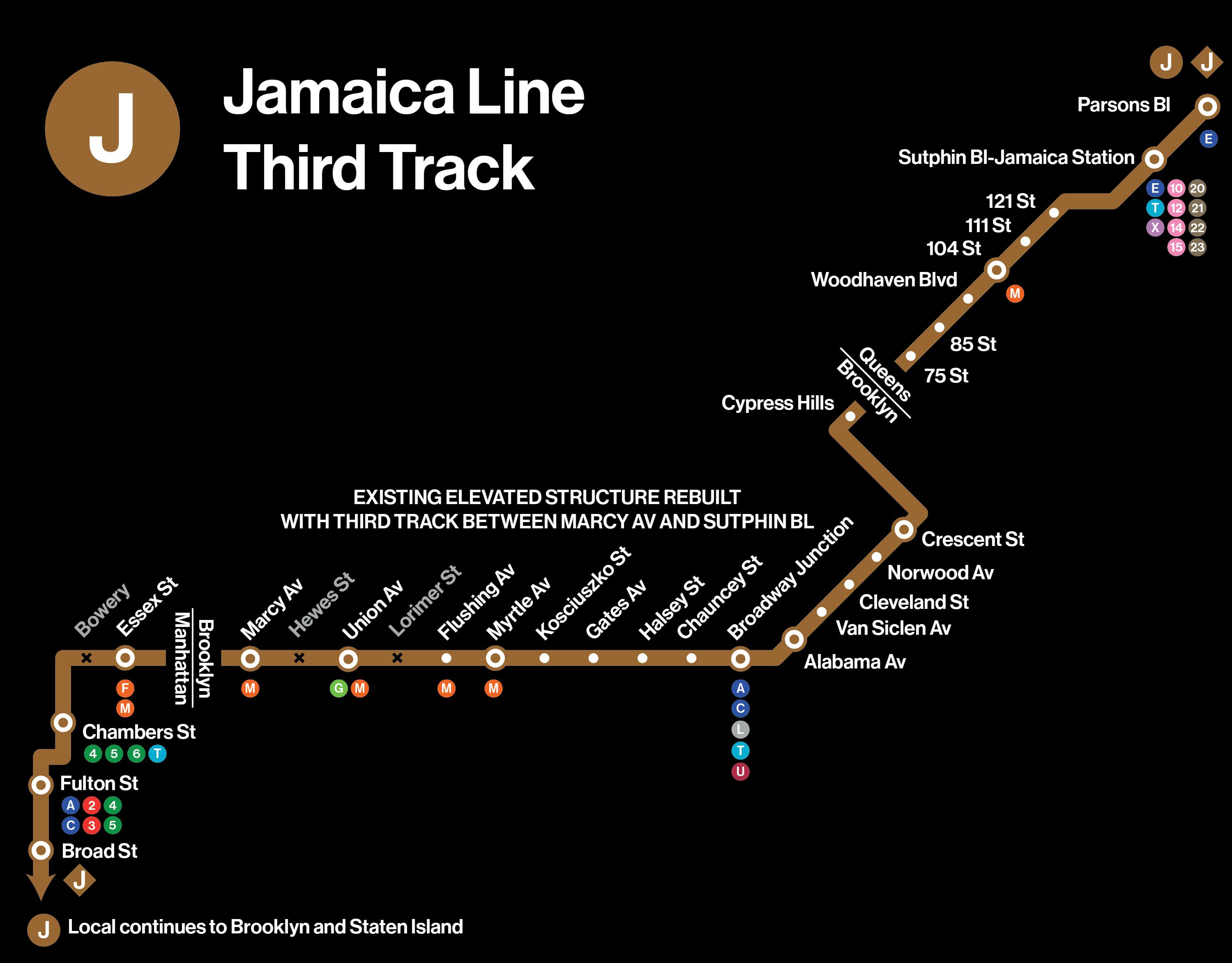

J: Third Track for the Jamaica Elevated

At the other end, the Jamaica Elevated Line should be upgraded to carry a third track between Sutphin Boulevard and Marcy Avenue, enabling peak-direction express service as proposed in the late 1950s. The Z train would be eliminated.

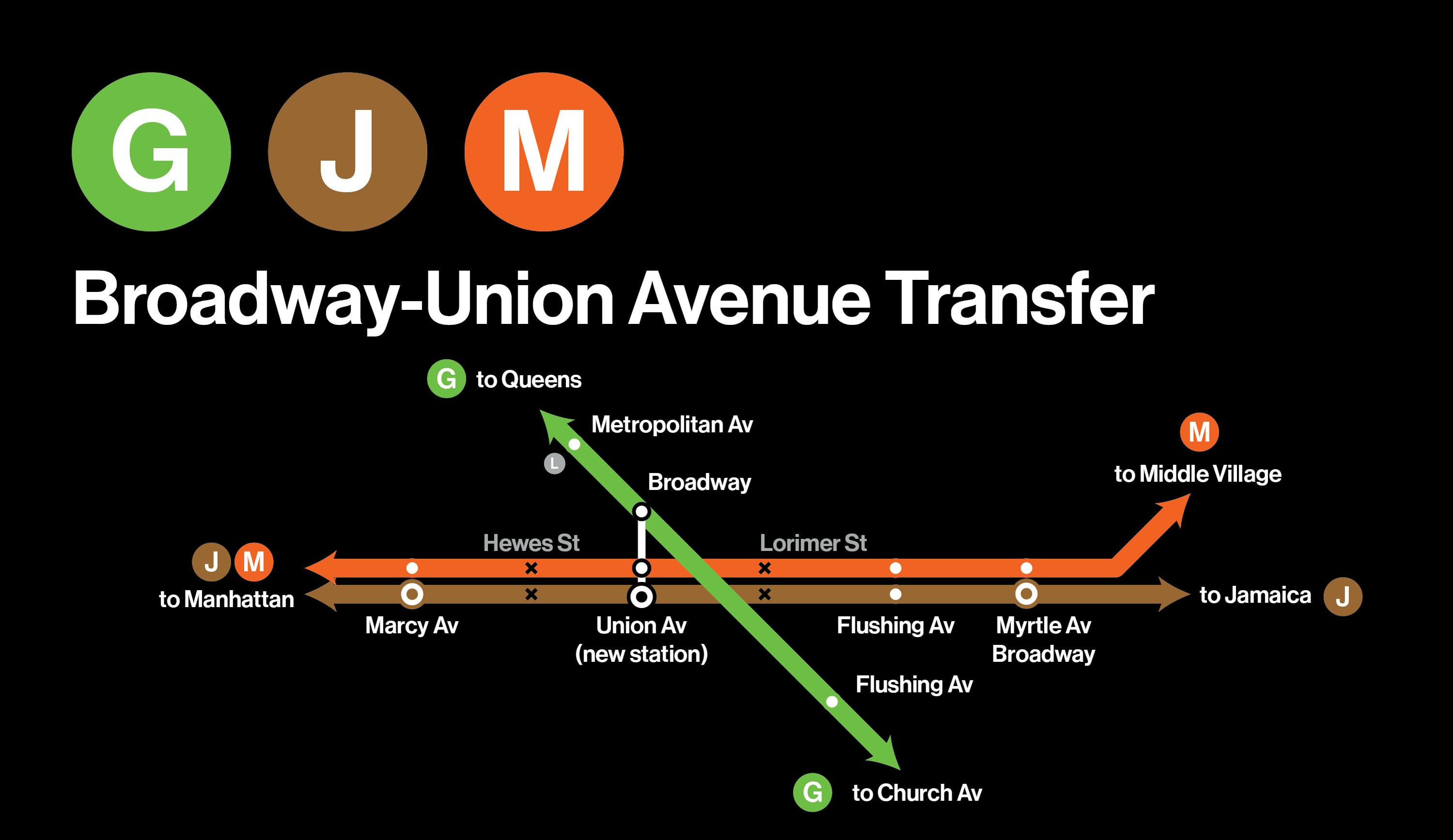

As part of this high-speed reconstruction, two stations in Brooklyn would be closed and replaced. Lorimer Street and Hewes Street are less than half a mile apart, and neither includes a transfer to the G train at Broadway. As part of any reconstruction of the Jamaica Line, Lorimer Street and Hewes Street should be closed and replaced with one express station at Union Avenue with a free transfer to the G train.

Bowery Station in Manhattan would also be closed. Formerly a busy transfer point to long-gone streetcar and elevated lines, Bowery is now obsolete, as it’s just too close to other, more useful stations. Spring Street on the 6 train and Grand Street on the B/D trains are a fourth a mile away or less. Slightly further afield, the enormous station complexes at Canal Street (6, J, Z, N, Q, R and W) and Delancey-Essex (F, J, M and Z trains) have many more options. Coupled with the need for a junction to handle trains from the Second Avenue Subway at Chrystie Street, it only makes sense to eliminate Bowery Station.

Serving subway deserts

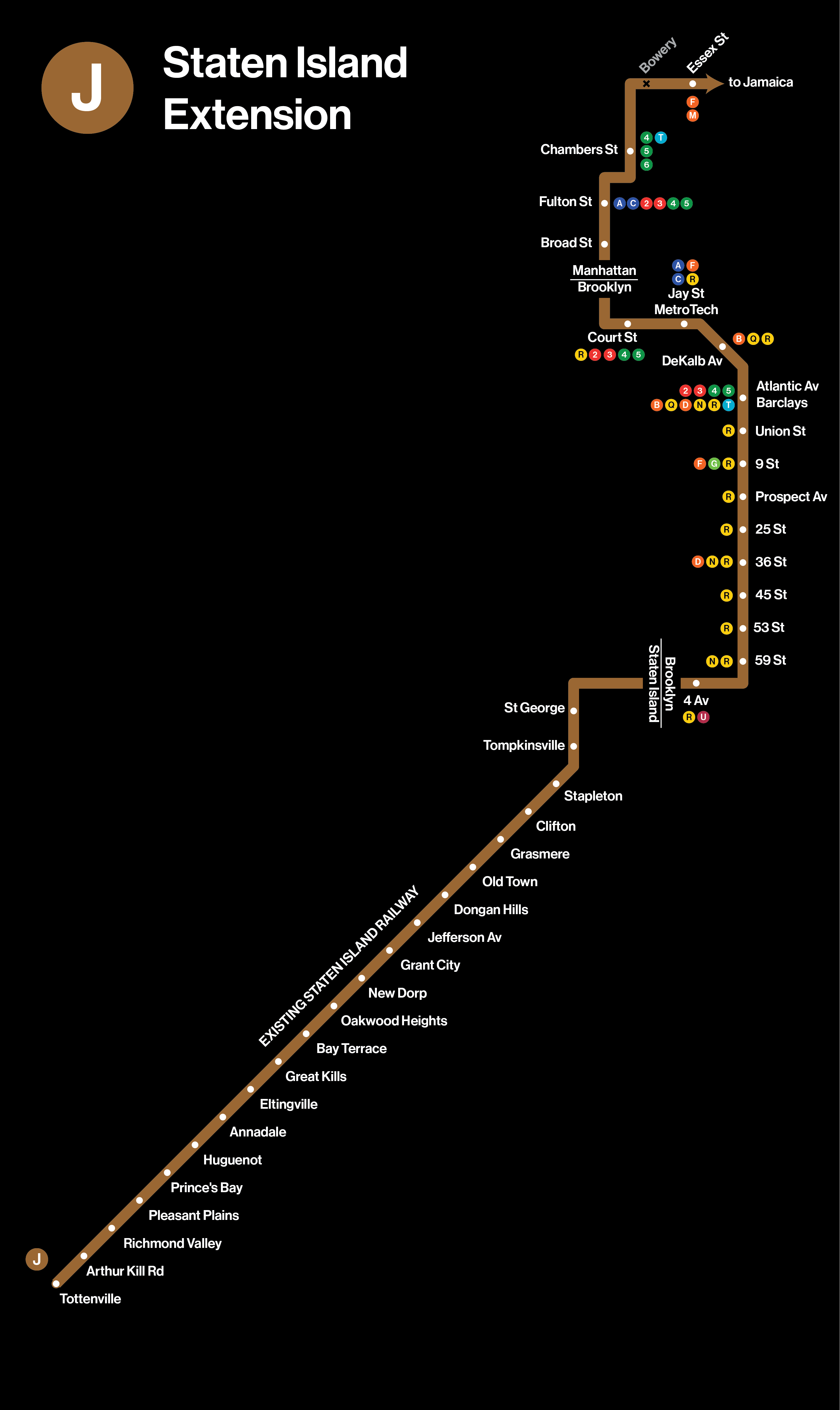

J: Staten Island Extension

Staten Island has been promised a subway connection since the early 20th century. There have been various plans over the decades to do so. In 1923, the City started construction on the Owl’s Head Tunnel, which was meant to connect the 59th Street-4th Avenue station in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, with the St. George ferry terminal on Staten Island. Trains would continue from St. George to the Staten Island Railway. Mayor John Hylan stopped construction in 1925, after a dispute with Albany.

The stations at both ends were designed with this connection in mind. 59th Street-4th Avenue Station has extra turnouts, which were meant to lead to Staten Island, and St. George Station on the Staten Island Railway was built similarly. In this map, Staten Island is served by an extension of the J train, which would share tracks with the R train between Manhattan and 59th Street, Brooklyn, and from there to Staten Island.

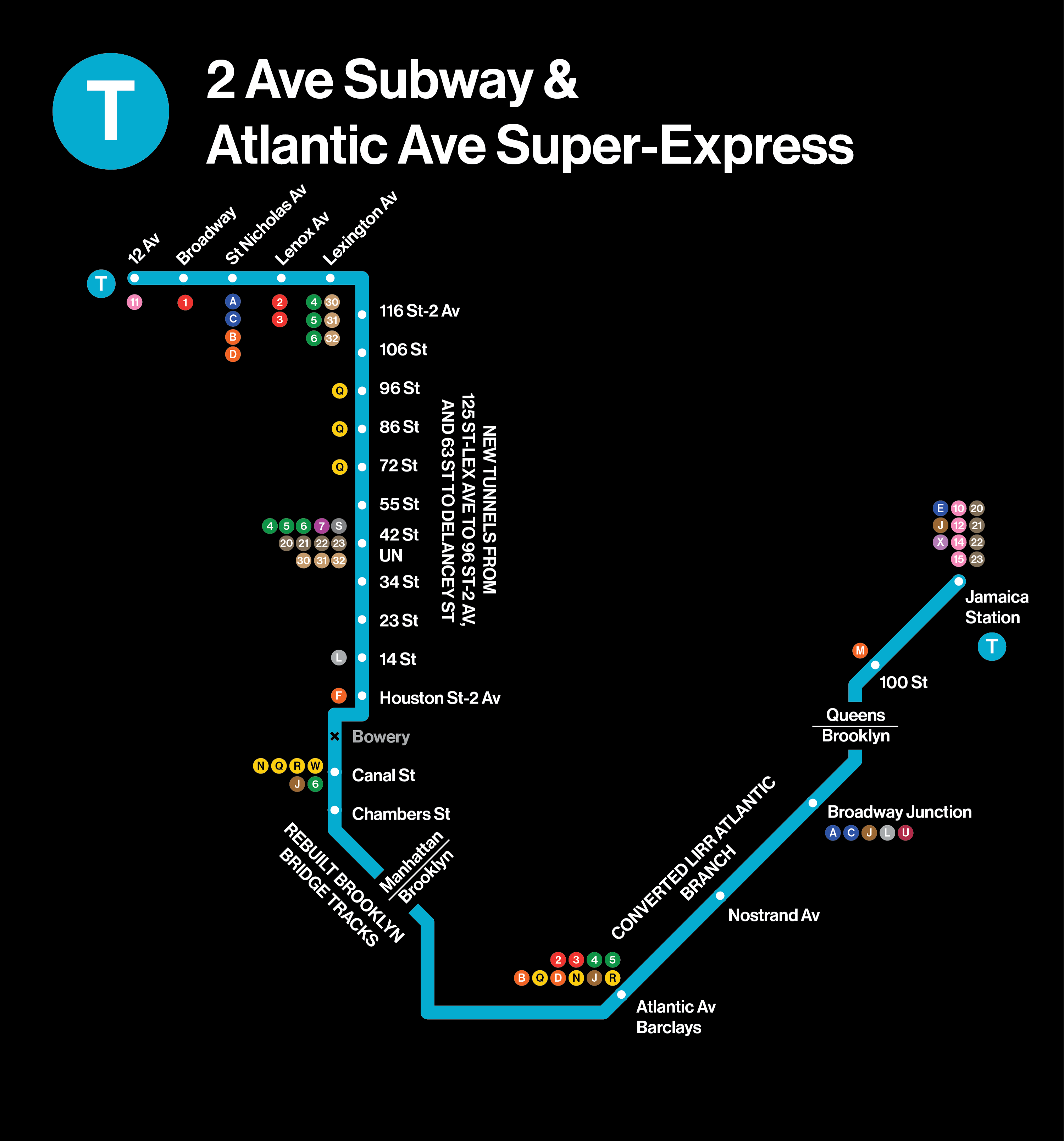

T: Second Avenue Subway and Atlantic Avenue Superexpress.

A full-length Second Avenue Subway, shown as the T train, is the centerpiece of this expansion plan. In Manhattan, it continues up Second Avenue and across 125th Street, providing a crosstown connection and relieving the overcrowded M60 bus. Below 63rd Street, the Second Avenue Subway continues straight down as far as Delancey Street. Between Delancey and Chambers Streets, the T train would use the unused trackways of the Nassau Street Line. After Chambers Street, the Second Avenue Subway would run over the Brooklyn Bridge to Brooklyn, using the ramps built over a century ago to reach the bridge. (This is something of a back-to-the-future plan, as the Brooklyn Bridge carried trains until 1944.) Once in Brooklyn, the Second Avenue Subway would proceed underneath Adams Street to the Cobble Hill Tunnel as far as Atlantic Terminal.

From Atlantic Terminal, the existing LIRR tunnel and elevated structure would be converted to carry subway trains as far as Jamaica Station, as proposed by the Regional Plan Association in 1999. In my version of the plan, the number of stops in Brooklyn and Queens is deliberately limited, because there is plentiful local service already. Between Atlantic Terminal and Broadway Junction, the A and C trains run one avenue block to the north. East of Broadway Junction, the A, C and J trains are within reasonable walking distance.

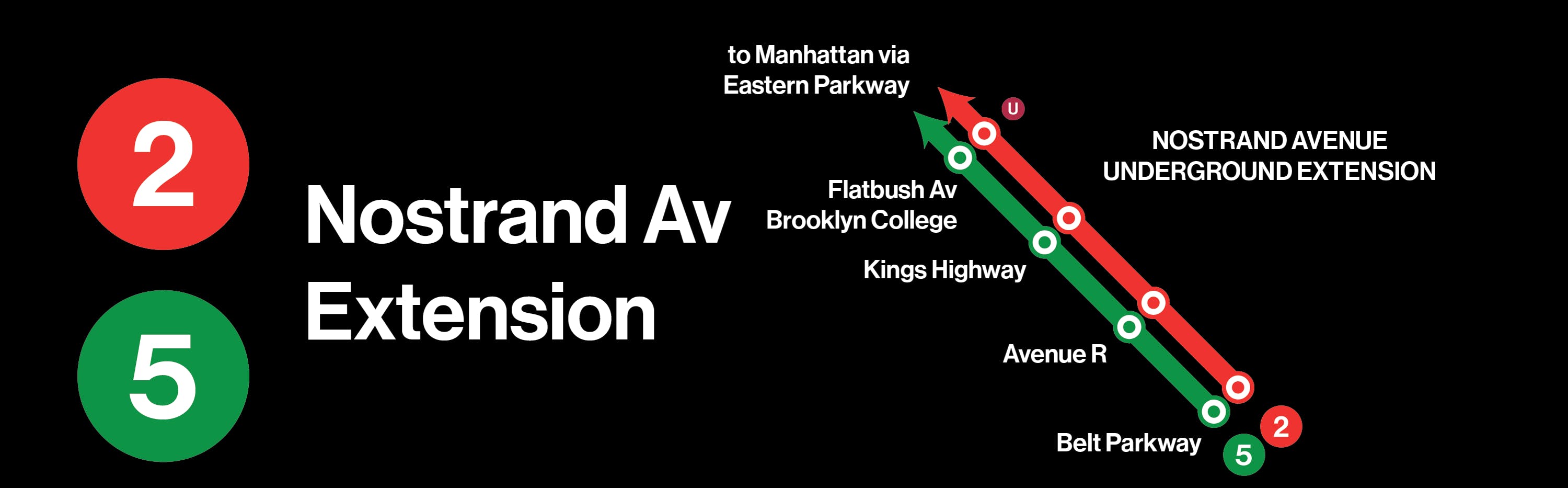

2/5: Nostrand Avenue Extension.

Plans to extend the Nostrand Avenue subway in Brooklyn beyond its current terminus at Flatbush Avenue have been put forth for nearly a century. It remains an extremely busy corridor even today. The B44-SBS route is the seventh-busiest bus route in the city, so the demand is clearly there for an extension from the current terminal at Flatbush Avenue to the Belt Parkway. This extension should also be coupled with a rebuild of Rogers Avenue Junction, easing a bottleneck that the 2, 3, 4 and 5 trains have had to deal with for a century.

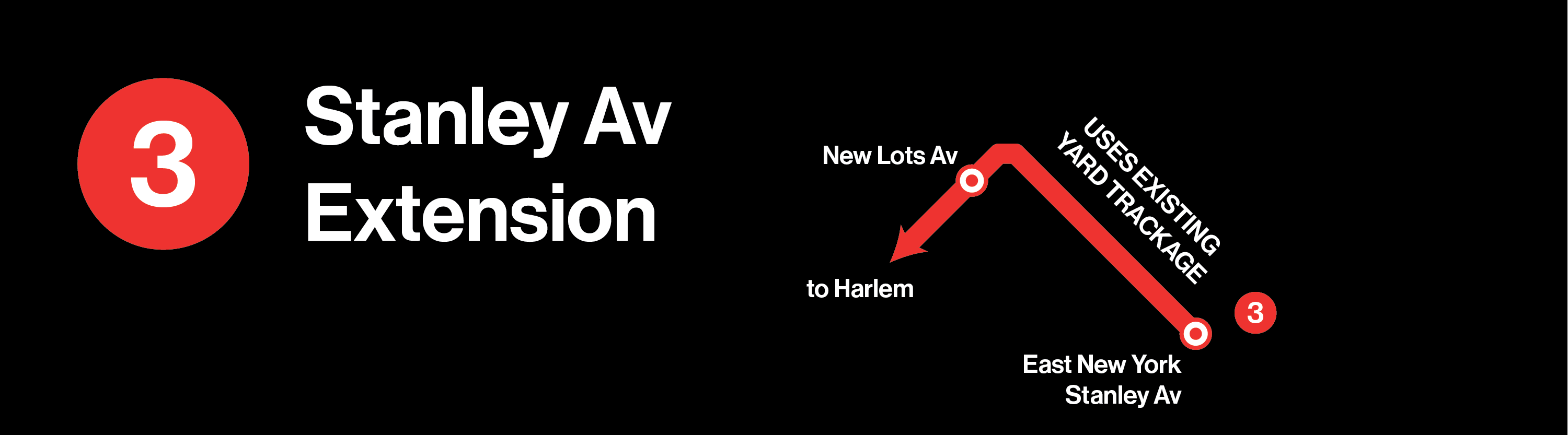

3: Stanley Avenue Extension.

The last stop on the 3 train in Brooklyn is New Lots Avenue in East New York, but the tracks actually continue for another half-mile to the southeast. This is a prime opportunity to redevelop a relatively underused industrial area at low cost.

4: Utica Avenue Subway

A Utica Avenue subway has been proposed multiple times over the last century, including 1929, 1939, 1968 and again in 2020, by none other than then-Borough President Eric Adams. Like the Nostrand Line, ridership on the B46-SBS route indicates that a subway is viable. The B46-SBS is the sixth busiest bus line in the city. The neighborhoods along Utica Avenue — East Flatbush, Flatlands and Marine Park — are subway deserts.