A child of the Bronx revisits his youth at Fotografiska and the Universal Hip-Hop Museum.

Currently, two time machines exist at different poles of cultural interest in New York City. In lower Manhattan’s upscale Gramercy neighborhood, the Fotografiska Museum houses one time machine — an exhibit called “Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious,” celebrating the 50th anniversary of the musical genre with select photos and artifacts dating back to the culture’s South Bronx origins of the early 1970s. Way uptown in the modern-day South Bronx sits the second time machine, in the form of the Universal Hip-Hop Museum exhibit “Revolution of Hip-Hop: 1986 to 1990,” featuring more photographs and mementos from rap’s golden age. Though each display merits as worthwhile in its own right, they’re both likely to leave hip-hop devotees feeling hunger pangs for something hard to convey.

I remember both the rise of hip-hop and its apogee well. Raised in the northeast Bronx’s Co-op City shortly after the housing development was opened for residents in 1973, with two sets of great-grandparents living in the South Bronx, those times and places were my playground.

Some of the nostalgic tableaux displayed on the walls of Fotografiska look like freeze frames from my wonder years. “Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious” succeeds the most when the exhibition goes beyond celebrity photography and actually engages with the ordinary people who supported and interacted with hip-hop as a cultural movement — as in Janette Beckman’s snapshot of Salt-N-Pepa alongside a young female bodega customer on the Lower East Side.

Growing up as a child of New York City during those days, my memories feel chock full of details that can’t possibly translate to a museum space, no matter how comprehensive, and I suspect that’s the way it is with every New Yorker’s childhood.

“A Perfect Match,” by the celebrated street-style photographer Jamel Shabazz, shows a teenage couple from 1982 staring through the window of a completely bombed (read: graffiti’d) subway car. The young lovers wear matching beige Lee jeans and striped polo shirts, their backs to the camera. The guy sports the shell-toe sneakers immortalized by Run-DMC’s “My Adidas” four years later. Without them even turning around, I’m certain their shirts are by Le Tigre. Because I lived through the era.

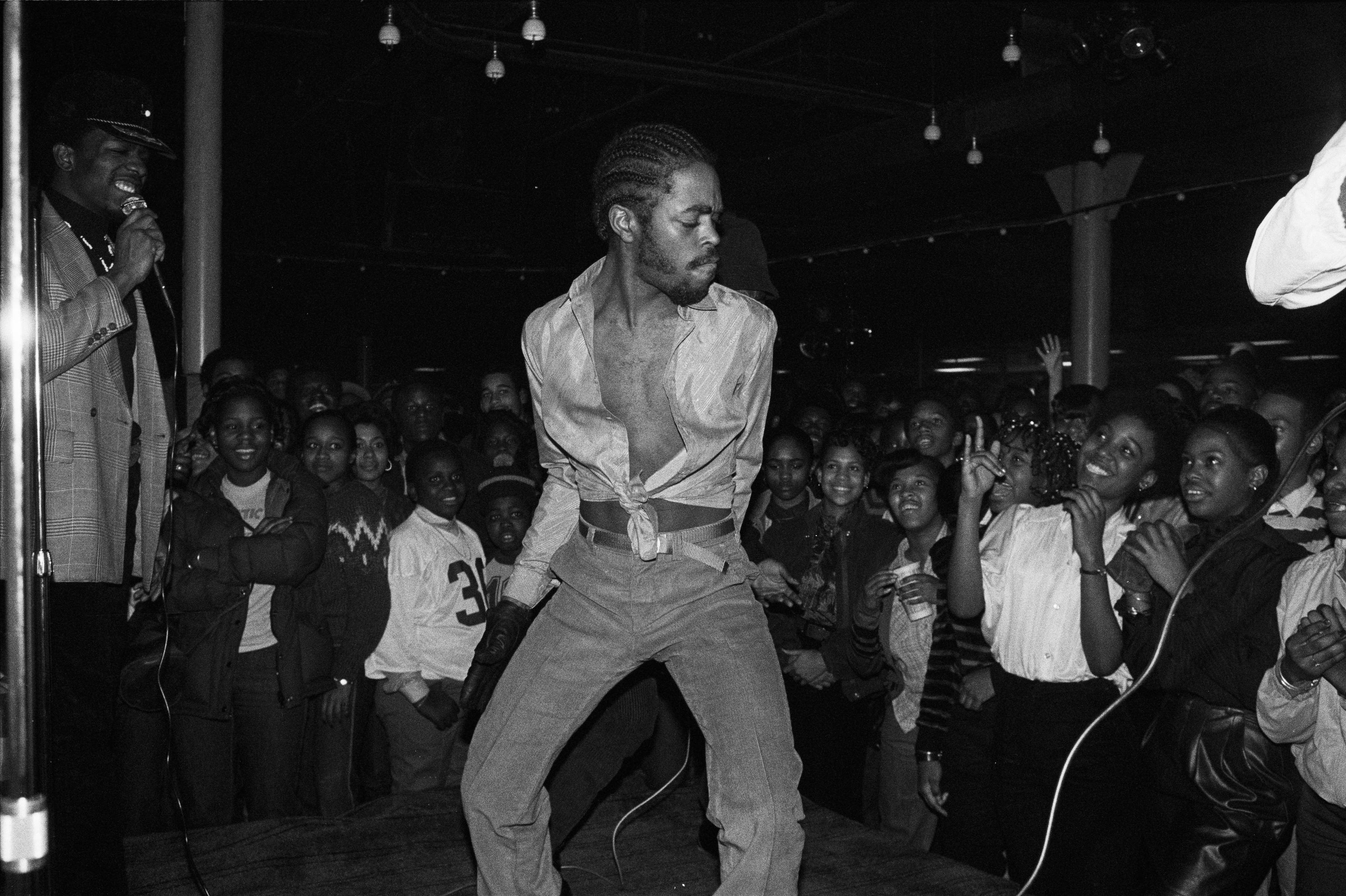

The same with Bronx-born photographer Joe Conzo’s snapshot capturing Cold Crush Brothers rapper JDL busting moves for a teenage crowd at Soundview Avenue’s Skate Palace. The Skate Key roller rink, miles away on White Plains Road, qualifies as my very first teenage nightclub — where I witnessed and partook in frontside sliding to songs like Melle Mel’s “The Message.”

Still, growing up as a child of New York City during those days, my memories feel chock full of details that can’t possibly translate to a museum space, no matter how comprehensive, and I suspect that’s the way it is with every New Yorker’s childhood. Every generation identifies with its own set of musical heroes, but for us, hip-hop meant more than music. This was (and to some extent still is) a quadripartite culture encompassing B-boys and B-girls (or breakdancers), graf artists, DJs and rappers. These four elements fostered community in the boroughs’ Black and Brown spaces, because we danced together, invaded MTA train yards together and came together at block parties and public park jams amazed at the diversity of music and MCs’ verbal dexterity.

So too, hip-hop never existed in a vacuum. I was only 8 when 6-year-old Etan Patz got kidnapped in Soho in 1979, wondering if it could happen to me. The murders of “.44-caliber killer” David Berkowitz registered fresh in my memory from 1977; I lived in the Bronx he’d terrorized. Kids like me whiled away hours at arcades playing Pac-Man and Space Invaders; broke apart and reassembled our Rubik’s Cubes; scoured Crazy Eddie for new rap singles; and recorded midnight-hour rap shows from WBLS and KISS-FM while David Letterman pioneered snark on his new late-night talk show. It was a piece of a cultural puzzle — albeit for many young people, the biggest piece.

The pre-pooper scooper NYC of hip-hop’s halcyon days made city blocks a hopscotch of dog crap landmines. The Times Square my father drove us through on our way to annual Comic Art Conventions at the Sheraton Hotel looked like a strobe-lit, scary adult funland full of XXX theaters, bumper-to-bumper gas guzzlers and dirty decadence. Meanwhile, hip-hop headed downtown to mix with the punk and hipster scenes via DJ Afrika Bambaataa, creating a cultural mash-up that gave clubs like Danceteria and the Mudd Club a nightlife vibrancy all but absent in downtown ’23.

To curate hip-hop is to tame it, and the whole point from the get-down was to channel rebellion.

Context is king, and though Fotografiska gets hip-hop’s seminal figures correct, it can’t hope to capture the essence of the time period’s gonzo atmosphere.

Yes, Fotografiska gave me some powerful twinges of my formative years being marketed back to me as I browsed the glass-encased photos of musical heroes from my youth: the Fat Boys, Marley Marl, Slick Rick, MC Shan, UTFO, on and on. Speakers overhead pumped the familiar three-note guitar snippet of Big Daddy Kane’s “Set It Off.” Could my school bullies from the Five-Percent Nation be lurking around the corner?

But for all that, something felt missing. Hip-hop, perhaps, is the last art form to belong in a carefully curated museum show. To curate it is to tame it, and the whole point from the get-down was to channel rebellion.

For example, passing display cases of eponymously titled 8-track tapes by Sugarhill Gang and Kurtis Blow, I recalled the first concert of my young life: the Krush Groove X-Mas Party at Madison Square Garden. A collective of rap’s finest — including Blow, LL Cool J, Whodini, Dr. Jeckyll & Mr. Hyde and Doug E. Fresh — stalked the auditorium’s main stage (Whodini on motorbikes!) in December 1985, a handful of thieves running around snatching gold chains off the necks of teenagers in the nosebleeds. Two concertgoers got shot that night, six others stabbed. Hip-hop wasn’t always museum safe.

So it was refreshing in a sense, though surely still a bit weird, to go way uptown for a second attempt at canonizing the art form. With its permanent location still under construction near the Major Deegan Expressway, the temporary Universal Hip-Hop Museum feels like a speakeasy. Part of the Bronx Terminal Market full of Applebee’s, Target, Home Depot and other shopping mall staples, ticketholders enter the museum with a sharp knock on the locked front door. Executive Director Rocky Bucano welcomes visitors inside for guided tours that begin with “the Tunnel,” a blackened hallway with flashing lights that resemble sound equalizer levels, as an old-school master mix pumps “Rock the Bells,” “The Bridge,” “My Mic Sounds Nice,” and more. Bygone hip-hop radio DJs like the late John “Mr. Magic” Rivas would’ve been proud.

A Dapper Dan-designed faux Polo Ralph Lauren leather coat from the Ultramagnetic MCs probably looks more impressive to Generation Z rap fanatics who never lived through the ’80s. Not so much to this aging original B-boy.

The Hip-Hop Museum has nothing on, say, the Black Smithsonian (aka Washington D.C.’s National Museum of African American History) as far as impressive cultural curation is concerned. Emerging from the Tunnel into the main space, a makeshift winding hallway full of 1980s concert posters, press clippings, clothing and record label plaques make up the totality of the exhibition. Unlike Fotografiska, most of the images on display are press-kit photos, with an occasional personal Polaroid. A Dapper Dan-designed faux Polo Ralph Lauren leather coat from the Ultramagnetic MCs probably looks more impressive to Generation Z rap fanatics who never lived through the ’80s. Not so much to this aging original B-boy.

Part of my cynicism, to be sure, springs from a commonplace reaction to the passage of time. Because wasn’t it just yesterday that Dapper Dan operated his 125th Street Harlem boutique, taking custom orders from rap royalty like Rakim, Salt-N-Pepa and Rob Base? Wasn’t The Village Voice arts weekly running rappers like De La Soul on its covers on a semi-regular basis? (The February 1990 edition on display reveals De La Soul Is Dead won their 16th annual critics poll.) Can rap’s so-called golden age really have passed a whole two decades ago?

That said, Dapper Dan legitimately collaborates with Gucci and Gap nowadays, The Village Voice hasn’t been a ubiquitous must-read in the city for quite some time, and De La Soul rapper David “Trugoy” Jolicoeur passed away weeks ago at 54. Time has passed. Hip-hop is in the history books, as 50th anniversary remembrances will continue to remind everyone all year long. And at the end of the day, it certainly belongs in them — as well as in our ears and hearts, as it continues to evolve.