The court’s imperative at this week’s hearing

Tomorrow, in federal courts in both Miami and New York, Americans will be able to see for themselves how the rule of law is kept alive. Of course, the Miami proceeding will be to arraign a former president of the United States on charges that underscore his contempt for any supervising authority. The New York proceeding has flown under the radar, in part, because it is about the city’s jails, a society closed to the outside world, and in part because, despite the escalating evidence of rampant violence and mismanagement, the crises have not broken the surface of the city’s conscience.

On Tuesday morning, however, the City’s adherence to the rule of law will be tested. Eight years of laboring under a federal consent decree aimed at abating the “culture of violence” that has defined the jails has resulted only in more barbarous conditions. By the end of 2022, the jails suffered the highest rate of deaths since 1996. And compared to the year when the consent decree went into effect to reduce the unconstitutional conditions of violence, almost every measure is up, with uses of force resulting in serious injury up 856%, stabbings and slashings up 559%, and on and on, until the numbers blur to numbness.

In the last 10 days, the compelling evidence of the City’s inability to curb the violence has been joined by growing evidence of the City’s unwillingness to do so. Instead of open and sober attempts to remake the jails, as it agreed to do under the consent decree, the City has instead treated New Yorkers to open defiance of the oversight of the monitor who is charged with assessing the City’s compliance. While we have reviewed the breadth and depth of the City’s recalcitrance recently, here are a few examples to give a flavor. In the legal equivalent of sticking its tongue out, the City has asserted it does not have to report deaths to the monitor. In brazen actions to cut the public off from key information about the jails, it has ceased announcing deaths in the jails. The City accompanied the ringing down the curtain on information with this runic “explanation”: that there is no obligation to provide the information as it was a “practice, not a policy.” And in an increasingly open war on oversight, aimed at neutering the supervisory authority of the Board of Correction, the City unilaterally cut off the Board’s 24-hour access to videotaped evidence of uses of force. Uses of force are the key measure of compliance of the consent decree.

At its core, a receiver stands in the shoes of a mayor, with executive powers over the department, and the authority to change agreements and regulations.

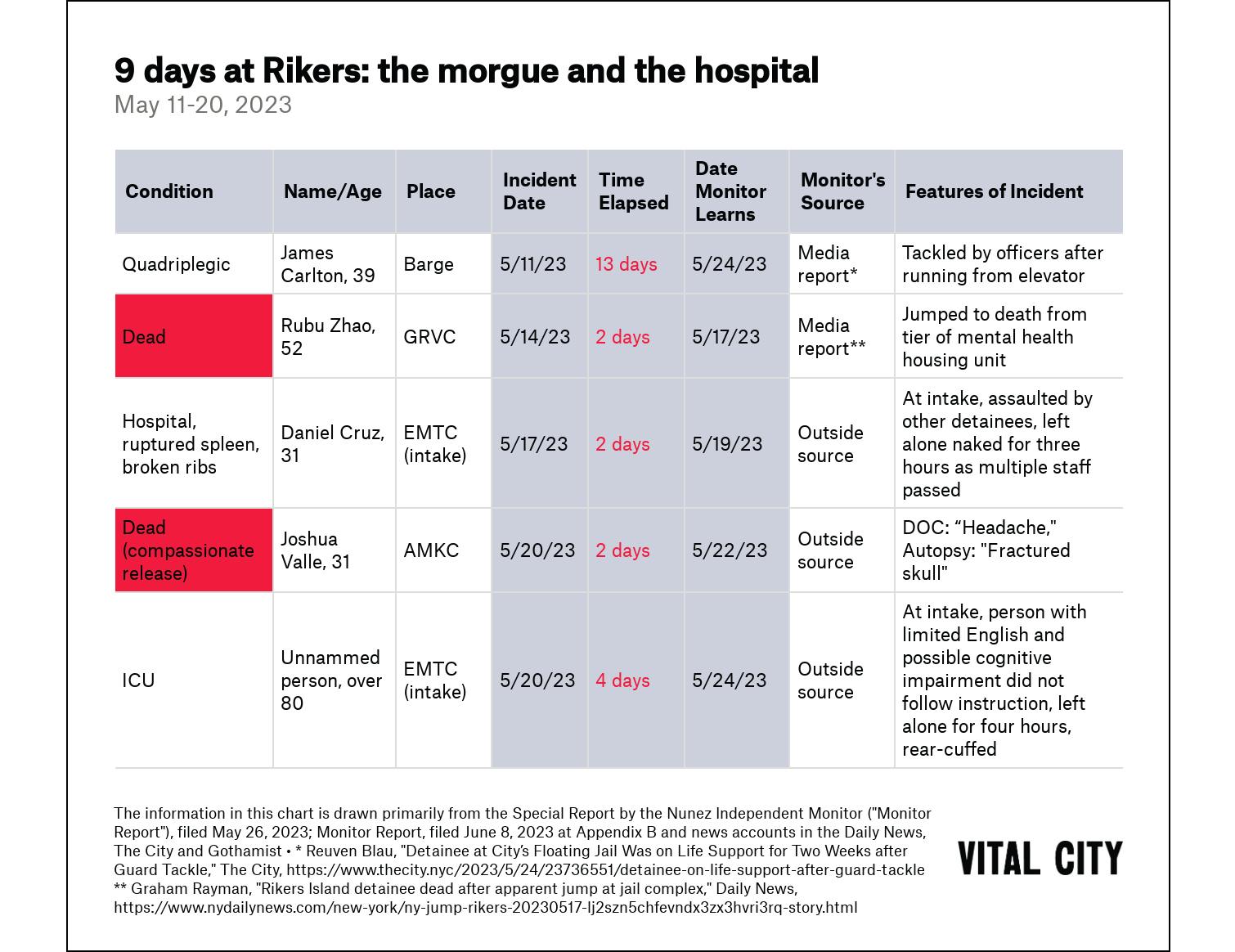

What has prompted this Tuesday’s emergency meeting at the court is a crisis of transparency that occurred over nine days at Rikers. The events over that brief stretch left two people dead, one quadriplegic and two in the hospital with life-altering injuries. The injuries are horrific and the course of events that led to each of the injuries reveal the deep dysfunction of the department — a man running out of an elevator is “taken down” by officers and left paralyzed; another is assaulted by other detainees, who rupture his spleen and break his ribs, after which the man is left naked and alone in a cell for three hours as staff passes by. These mirror the dysfunction that caused the highest rate of deaths since 1995, including a detainee who slit his throat with a razor as officers stood by, and another who choked on an orange in an unstaffed unit as his fellow detainees banged on the glass for help, among many other incidents.

In the Special Report on the May deaths and injuries, the monitor describes how the Department of Correction not only failed to advise him of the events but obdurately insisted that it had no obligation to do so. The hiding of the ball raises another question: If this record of destruction and mayhem — covering four jails, each with a separate staff of employees — was not reported by the jails’ administration, not because of negligence but because of intention, what else has gone unreported? Were there more than the three deaths reported this year? More assaults and injuries?

For all the monitor’s knowledge and skill, the “monitoring” of the situation is unequal to the problems if the City — the prime mover — cannot, and now, apparently, will not act. A federal receiver has different powers from a monitor, powers that are negotiated by the parties to the consent decree and ultimately decided upon and ordered by the court. But at its core, a receiver stands in the shoes of a mayor, with executive powers over the department, and the authority to change agreements (for example, collective bargaining agreements) and regulations (for example, procurement rules).

These are mighty powers, reserved for that last resort — a place that we have now reached. To order the appointment of a receiver, the court must find some combination of grave and immediate threat of harm to the plaintiffs, the failure of less extreme measures, the limited utility of continuing to insist on compliance with current orders and the lack of effective leadership.

At a moment so devoid of sunlight, the city and democracy would be well-served, were the court to grant the plaintiffs their oft-proffered request to file a motion requesting a receiver.

Oh yes, bad faith is also on that list. While it is a balancing test, meaning the court must not find every element in equal degree, the nine days at Rikers and all that has preceded and succeeded them, provide firm support for a finding of bad faith as well. When in an unguarded moment, the commissioner urges that an incarcerated person close to death be compassionately released to get him “off the count,” so that the death will not appear in the public tally of the dead, the balance tips to bad faith. When the commissioner in an apparently uncounseled letter, not only thumbs his nose at the monitor’s authority by insisting the City is not required to report deaths, but also urges that the monitor deep-six the apparently inconvenient evidence of ineptitude, malice and worse, lest it “fuel the flames of those who believe we cannot govern ourselves,” the evidence of bad faith mounts.

We are at a turning point. At a moment so devoid of sunlight, the city and democracy would be well-served were the court to grant the plaintiffs their oft-proffered request to file a motion requesting a receiver. The filing of the motion does not end the question. After all, the City will respond with its motion and the court will need to consider all the facts and arguments.

Thus far, the department has exercised a monopoly on the information that feeds the monitor and the court and thus the public. In a democracy, monopolies on information do not have much to recommend them. But when they are corrupted, as this one is, then opening up the sources of information could provide the court and the public with much-needed information about the advantages and disadvantages of a different, and, we wager, better way to be governed.