First time tragedy, second time, farce. In 2022, the eighth year of federal oversight, the conditions inside New York City’s jails were both tragedy and farce. Fixing them will take will, exercised without fear or favor.

It is rare that a municipal government advocates for the abolition of its jail system. But in a world where actions speak louder than words, decades of unabated brutality and mismanagement are making a better case than any advocate can. The stakes are high and the costs, in human suffering and in damage to democracy, immediate.

To a reader new to the escalating crises in the City’s jails, located on Rikers Island in the East River, this may seem like hyperbole. Sadly, it isn’t. Three conditions, present in different degrees for many decades, now combine in hydra-headed dysfunction: astonishing rates of violence; long periods of incarceration (more than a year) in jails that are intended for the temporary housing of the accused; and deep uncertainty about how, whether, when or where new facilities will be built to replace the old ones that are crumbling beyond use, with their very walls turned into weapons by those inside.

New York City’s jails have never been held up as an exemplar of correction. A history of Rikers out just last week makes that case in the compelling and horrific testimony of many who have passed through its gates over the decades. But the persistent and deepening crises signal that something is rotten in the state of the jails, something structural and longstanding that requires dispassionate scrutiny of reliable information and steady action over a sustained period of time. Otherwise, in an ocean of problems, the City will be measuring out solutions in teaspoons.

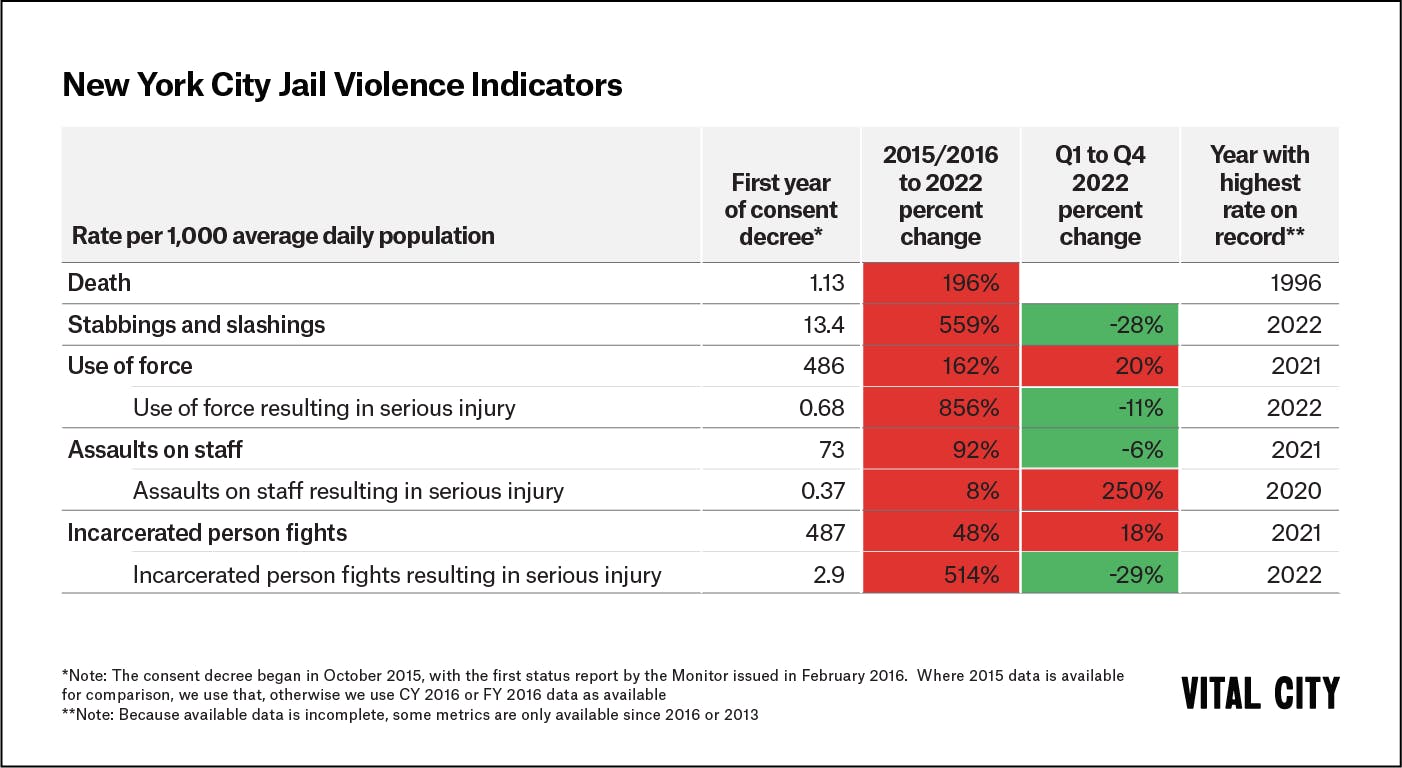

Every available measure of violence is exponentially higher than in 2015 when the City submitted to a federal consent decree aimed at reducing the then-unconstitutional levels of violence.

If the jails continue in their current condition, they will, as the most brutal expression of state power, simply fuel the cynicism and disillusion that has spurred increasing use of the term “criminal legal system” in place of “criminal justice system.” Reducing the violence is important for every human reason but also because it continues to erode the system’s, whether legal or just, already shaky hold on legitimacy.

Curbing violence

Deaths, stabbings and slashings, the most sobering barometers of jail conditions, have not been this bad in decades, if ever. This is despite the Department of Correction’s Action Plan intended to bring about progress and prevent a federal judge from imposing a draconian remedy beyond the current consent decree. The last time the jails suffered 2022’s rate of death was 1996. (See chart 1.) Then, New Yorkers were being murdered in record numbers, and the jails were jammed to the gills — so full that, as one former correction commissioner recounted, the Department of Correction ran buses to nowhere all night long so those incarcerated would have someplace to sleep. Fiscal year 2022 clocked the highest rate of stabbings and slashings on record (dating back to FY 1995). (See chart 2.)

Every available measure of violence is exponentially higher than in 2015 when the City submitted to a federal consent decree aimed at reducing the then-unconstitutional levels of violence. Indeed, the violence is so high that getting back even to those unconstitutional levels is but a dream. In comparison to then, deaths are up 196%, uses of force resulting in serious injury up 856%, stabbings and slashing up 559%, and on and on, until the numbers blur to numbness. (See Summary chart.) Last year, in the most explicit recognition that the jails could provide neither care nor safe custody, the then-commissioner sent a letter to every decision-maker in the justice system — judges, prosecutors and defenders — begging them not to send people into the city’s jails.

With deaths, stabbings and slashings setting new records in 2022, it would not be surprising if judges weighed the risks of harm in jail, including the lack of access to medical care now documented in the courts, before detaining people.

Numbers tell us a lot, but, of course, not everything. First, they are incomplete — hard to come by, hidden by both omission and commission. In a telling development last week, there was a brazen sign from the City that it would not abide by its statutory obligations to provide information to its oversight agency, the Board of Correction: The City unilaterally revoked the Board staff’s independent and unfettered access to all camera footage. This footage, of course, is key evidence in investigating complaints, uses of force, deaths, staffing and enforcement of all minimum standards.

We would like to be heartened by a moderating trend over 2022 in some of the other indicators. But the numbers are head-scratching and too higgledy-piggledy to provide confidence.

It is this fickleness of access and reporting that causes Vital City to rely most heavily on the number of deaths and the number of stabbings and slashings as the most reliable indicator of conditions within the facilities.

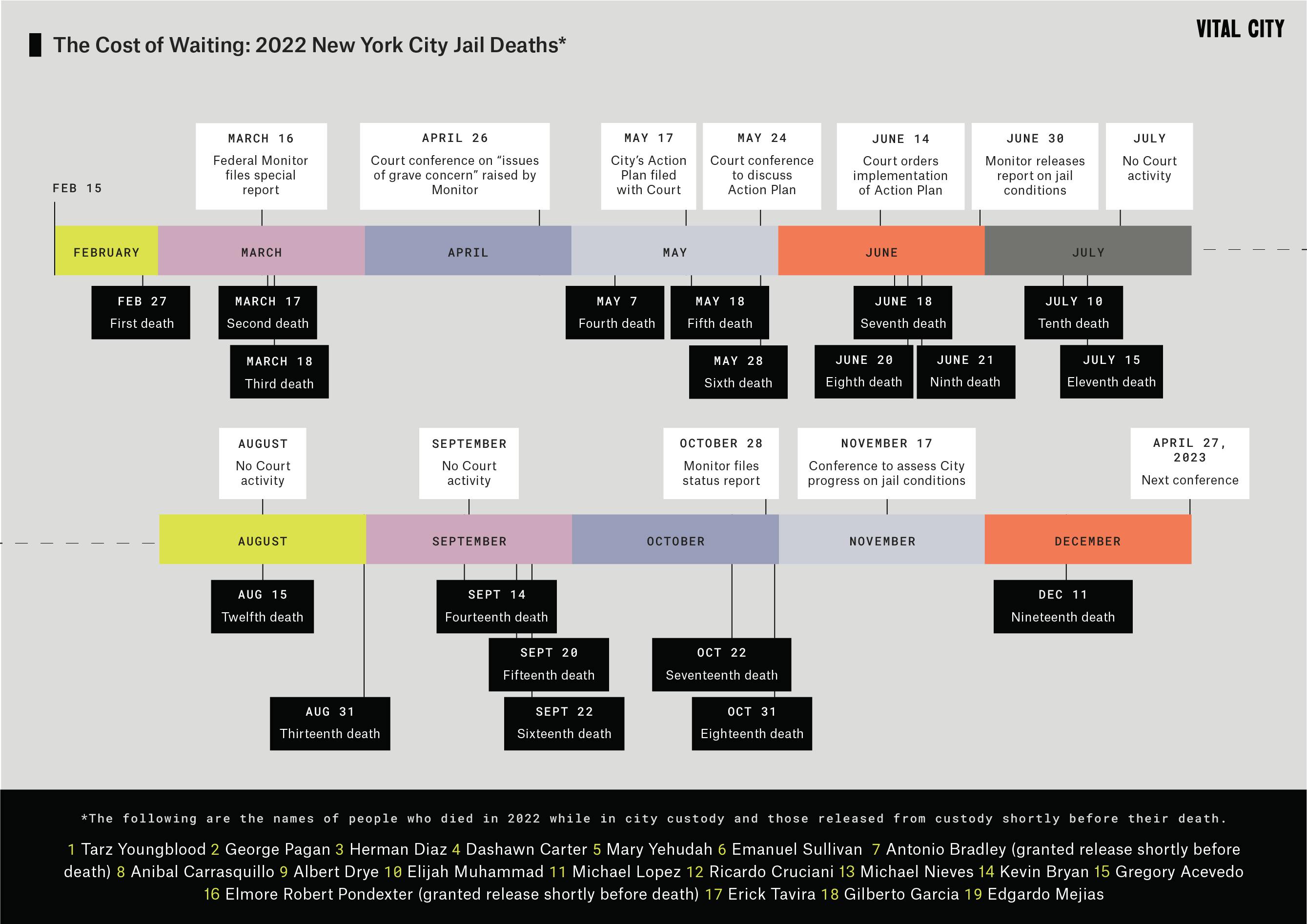

Death is different. It is a number that stands alone. It holds up a mirror to the conditions in the jail, a bellwether of despair and mismanagement. Last year’s record 19 deaths in or just after custody reflected the full panoply of misery and dysfunction: Six died by suicide; some of these people suffered from mental conditions. Eight died from the failure to adhere to basic management: Herman Diaz choked on an orange in an unstaffed unit as his fellow prisoners called for help that did not come; Michael Nieves managed to find a razor and slit his own throat, bleeding out as officers watched; Gregory Acevedo leapt to his death into the East River after scaling the barbed wire wall of a recreation yard, with officers within sight.

Though deaths are a reliable indicator of profound dysfunction and negligence, this year New Yorkers have been treated to the spectacle of what some are calling “dirty discharges,” the mortally ill or wounded released to hospital care hours or days before death so they do not appear on the official death count. Compassionate release is an important part of ensuring the humane treatment of those who are gravely ill or dying, but it should not be used to cook the books.

Stabbings and slashings also provide a kind of accountability that is missing from other measures. These injuries require clinical attention — from an agency different from the Department of Correction — and thus are a reliable barometer at a time when Correction is notorious for inadequate, missing and sometimes mendacious record-keeping.

Following the trendlines with a finer degree of attention is also instructive with respect to where the court might ask more probing questions. For example, the City has held up as promising a new violence prevention program in a facility for young adults (RNDC) where violence was most concentrated at the beginning of the year. The hope was that the program — never described in detail publicly — would have an ameliorative effect and thus be suitable to use in other facilities. After a period of abating violence, however, the rate of incidents in RNDC in December 2022 returned to January 2022 levels. (See Chart 3.) What are we to make of this? Without more information, it is hard to tell.

We would like to be heartened by a moderating trend over 2022 in some of the other indicators. But the numbers are head-scratching and too higgledy-piggledy to provide confidence. For example, why are assaults on staff down modestly but assaults with serious injury up significantly? Why are fights among incarcerated people up significantly but fights resulting in serious injury down even more? Are dropping stabbings and slashings over the course of 2022 because peace has broken out, if modestly? Or are there simply more lockdowns, one way to reduce violence without advancing progress over the durable long term? Many important facts aren’t known publicly — and perhaps not known within the department — each of which could have an effect on violence: What is the status and take-up of programming; Are new admissions housed promptly and appropriately, a question that just this week has become the subject of a contempt proceeding before the federal court.

Some things we can be confident are not the problem:

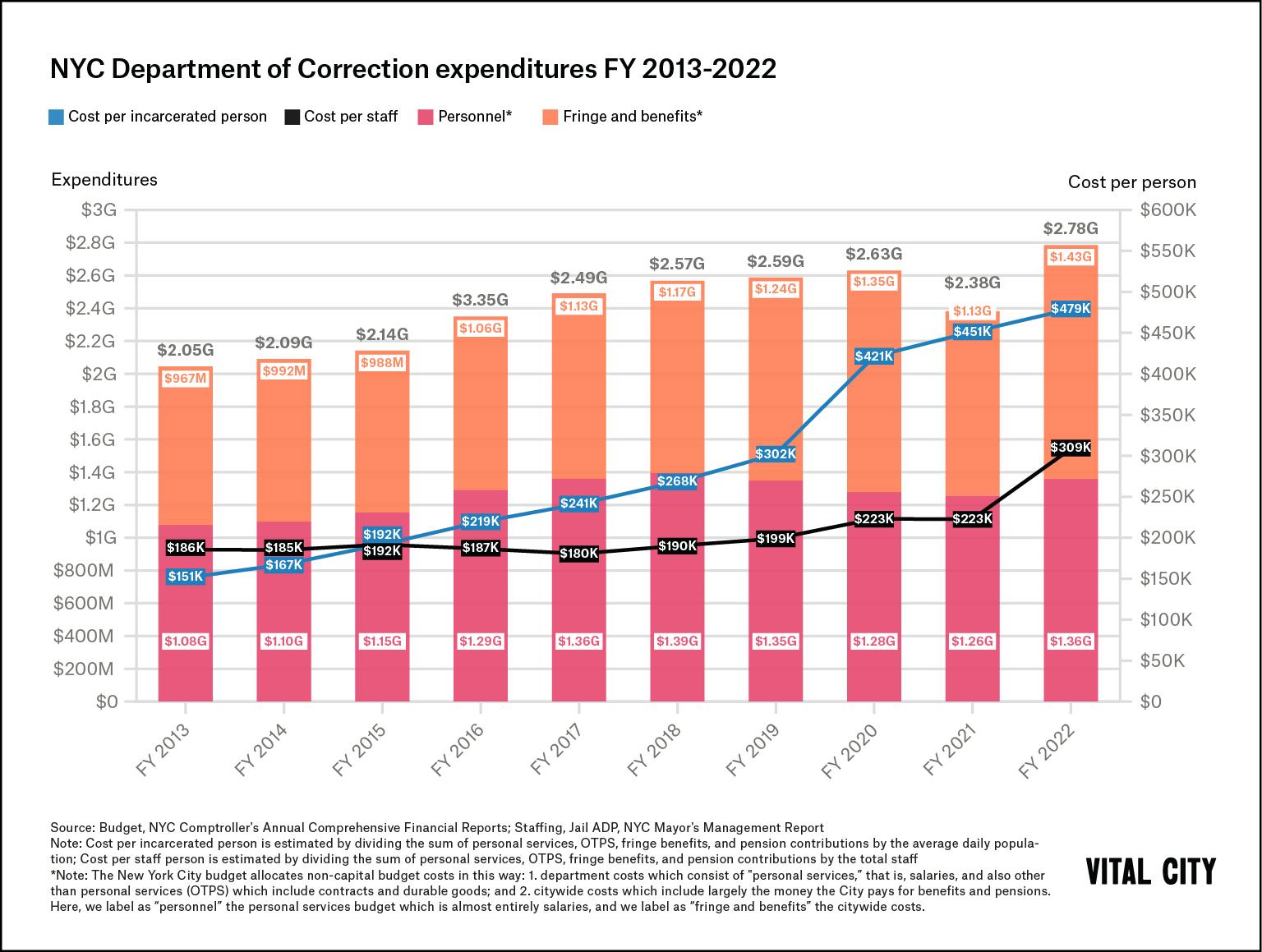

It is not for lack of staff. The jails are the most richly staffed on the face of the planet, with 1.6 staff per every incarcerated person. (See Chart 10.)

It is not for lack of money. The jails are among the most richly funded departments in the country with approximately $500,000 spent for each person incarcerated per year. (See Chart 9.)

It is not for lack of oversight structures: There is the State Commission on Corrections, the City’s Department of Investigation and Board of Correction and the New York City Council.

It is not for lack of trying. Indeed for decades spanning five consent decrees, eight mayors and 24 commissioners.

The answer is anodyne and seemingly bureaucratic in the face of the gory realities. It is mismanagement over the course of decades. As the federal monitor’s reports describe in excruciating detail, the mismanagement is now evident in proportions that bespeak the complete collapse of the Correction Department, what the monitor has termed a “broken system.” Lack of this basic control infects everything and spurs the pervasive culture of brutality and impunity. Just last week, the New York Times reported the head-spinning fact that the DOC staff responsible for regulating sick-leave abuses were themselves under investigation for, yes, taking multiple sick days that remarkably fell on Mondays, Fridays or around holidays.

So what can be done and where does this leave the court? Following a March five-alarm fire report by the federal monitor, the court ordered an Action Plan to improve conditions. Despite the “emergency” cited by the monitor and court, the court’s pace has been languorous, with one check-in on progress in November 2022 and another scheduled for late April 2023.

The court is in the unenviable but singular position to improve conditions, both by ensuring that accurate and complete information is forthcoming, scrutinizing whether the City’s actions are having an effect, and forecasting whether the current pace or another is the route to improvement. It has the longevity that no mayor or commissioner has and the power that no other entity has to keep the City’s feet to the fire. But to push progress with the urgency that conditions demand will require a more searching inquiry, not just about facts but also about the capacity and will to bring about change. This will necessarily tread on uncomfortable territory because the crucial issue of will is bound up with all the dynamics of power and obligation that haunt the operation of the department.

One example: Despite the glut of staff, there are not the right kind of staff at the right levels. A hollowing out of middle management — the engine of any organization — some years ago, combined with requirements in law and agreement to promote only from within, have left the department short-handed in the management apparatus of wardens, deputy wardens and captains needed to run the nine jails. Those prohibitions stem largely from efforts to protect unionized uniformed staff.

For several years, the federal monitor has urged the City to take the actions that would permit hiring from outside to fill these crucial spots that could not, because of the gap in ranks, be filled just by internal promotions. Instead, the department proposed a Rube Goldberg arrangement featuring parallel civilian and uniform managers of the jails — the civilians ostensibly installed to brace the weak management, but reporting to assistant commissioners four levels below the commissioner, while the uniforms reported directly to the commissioner, skipping several levels of command. (Vital City wrote about this issue here.) This unworkable workaround was a transparent attempt to install management without ruffling union feathers.

It didn’t work. In November 2022, the monitor and the City returned with what was hailed as a breakthrough agreement: The City would seek an order permitting it to hire eight wardens from outside existing ranks. As the U.S. Attorney trenchantly pointed out, wardens can’t do the job effectively without deputy wardens and captains. So, while the concession was celebrated in the courtroom, it is unlikely to produce results.

Left unsaid but perhaps key to understanding why, after years of urging, the City made only this grudging move may be this: Deputies and captains are union positions and wardens are not. Hanging heavy is the memory of the union several years ago sidelining the buses to Rikers Island apparently to stop the transportation of an incarcerated person due to testify against two correction officers in a brutality case.

Where do we go from here? In many ways, the court has a monopoly on available information and the power to force change. (Elsewhere, Vital City and others, including several former Department of Correction commissioners, have recommended the installation of a federal court-appointed receiver to stand in the shoes of a commissioner and have the day-to-day operational power to cut through current impediments. We continue to urge serious consideration of this idea.)

In a process that takes time, the court is a stabilizing power. And in a process subject to all the pushes and pulls of urban politics, the court alone can act solely and completely in the best interests of those incarcerated and those who work in the jails.

Reducing the length of time that people stay in the city’s jails

Since January 2019, the length of time that people stay in the city’s jails has grown from 73 days to 108 days. That is a problem in its own right — but also because the longer people stay, the higher the likelihood for violence, as uncertainty about the future increases, tensions mount and disputes escalate. Violence also extends time in jail, as new cases are brought related to the incident in jail. During the height of COVID, court operations were suspended except for the most serious cases, backlogs increased and stays became even longer.

A part of the Action Plan is reducing the amount of time spent in custody. But what is being done and how will this be publicly disclosed?

Because the size of the jail population is a function of how many people go in and how long they stay, the increasing lengths of stay have unnecessarily swelled the population. In December 2022, more than one in four people detained pretrial had been held for over a year.

Addressing this problem is complicated because delay can be the result of many different facets in a court case, each controlled by different players, each of whom answers to a different boss.

A part of the Action Plan is reducing the amount of time spent in custody. But what is being done and how will this be publicly disclosed? This should be a regular part of the City’s reporting to help diagnose the causes behind the delays.

Transitioning to new facilities

The structural issues in the city’s jails are not just about management. The buildings themselves are dilapidated. Following an ardent campaign, the previous mayor agreed to “close Rikers,” and with the support of the City Council proposed a plan to build four humanely and intelligent designed borough-based jails that are closer to courts, detainees’ families and lawyers, and that would hold a maximum of 3,300 people total.

Mayor Adams has said he believes the 3,300-person population target will be difficult to reach and suggests the City begin working to implement a Plan B.

The pressing question for those who care about the conditions in the city’s jails today is whether and how, in the years between now and when either a Plan A or a Plan B is conceivably operational, Rikers and the department that run it can conceivably be salvaged under current management. If they cannot, either plan will, in every way that matters, be a continuation of the brutal status quo.

The Data

*Note: The consent decree began in October 2015, with the first status report by the monitor issued in February 2016. Where 2015 data is available for comparision, we use that, otherwise we use CY 2016 or FY 2016 data as available. Similarly, we sometimes show information by fiscal year or calendar year. This is because some information is available by fiscal year which for New York City runs from July 1 to June 30. (We are currently in February of FY 2023.) Some information is available only by calendar year.

1. People are dying — at the highest rate since 1996 and almost three times the rate in 2015

- 2022 had the highest number of deaths (19) since 2013.

- 2022 death rate is almost three times the rate in 2015.

2. Stabbings and slashings are 50% higher than FY 1995, the previous record high

- 2022 rates of stabbings and slashings exceeded 2021 levels by 12%, 2019 levels by 415% and 2016 levels by 527%.

3. The violence isn’t spread evenly across the island

- The Robert N. Davoren Complex (RNDC), where young adults are housed, started the year with high rates of stabbings and slashings. Rates declined in May but by December had rebounded to January and February levels.

- As rates of stabbings and slashings declined in the late spring in RNDC and OBCC (used before its closing as an intake facility), the rates of violence shot up in the George R. Vierno Center (GRVC). GRCV rates declined into the end of the year, but remained with RNDC one of the highest on the island.

4. Detainees are being seriously injured at higher rates

The rate of use-of-force incidents resulting in serious injury is nearly 9.5 times higher than six years ago

- FY 2022 incidents were down from FY 2021, but preliminary data show FY 2023 incidents trending back up.

- Despite fewer overall incidents in FY 2022, the rate of incidents resulting in serious injury is up in FY 2022 from FY 2021 and up 4.2 times from the FY 2019 rate.

5. Rates of serious staff injuries are flat or slightly down

Assaults resulting in serious injury remained stable from 2021 and were down from 2019 and 2020

- 2022 incidents were at the lowest level since 2017.

- 2022 rates were 30% below 2021 levels, 7% below 2019 levels and 92% above 2016 levels.

6. Incarcerated people are injuring one another at six times the rate of 2016

Rate is higher than any other year since 2016, the first year of the consent decree and the first year of consistently released data

- The 2022 rate of fights resulting in serious injury were the highest since 2016, even though the total number of fights declined.

7. Nearly a quarter of officers remain unavailable to work

Last year, 23% of officers were not available to work, an improvement over the previous year but far higher than the two years prior

8. The death count is growing

19 people have died in 2022, 18 since the federal monitor issued his “Special Report” on state of violence

9. The cost to hold a person has almost doubled since FY 2016

10. The staff-to-incarcerated person ratio has grown over the past decade

There are now 1.6 staff for each incarcerated person

Jail ADP:

Jailed over one year: