What if City leaders allowed everyday residents to guide the programming and design of urban spaces?

At the height of the pandemic, when many of New York’s streets were eerily quiet, a thoroughfare in Jackson Heights, Queens — 34th Avenue, now called Paseo Park — was full of life. Children were learning to ride bikes, newly arrived New Yorkers were learning English, local dancers were teaching salsa, and thousands of New Yorkers were finding reprieve in the outdoors. The avenue had become the neighborhood’s new place for safe social gathering, exercise, outdoor “school” and cultural events.

Open Streets are not new to New York; there are dozens all over the city. What made and still makes Paseo Park different is that it is longer than typical — 26 blocks (1.3 miles) in a residential area — and is supported by residents and schools (serving 7,000 children), not commercial businesses. “In our neighborhood, we don’t have a community center. We have a tiny park. All of a sudden, in one of the neighborhoods hardest hit by the pandemic, we have 26 blocks of streets to deliver community run programming — cumbia, knitting, running races, pre-K registration -— whatever community members want to organize — that is convenient to access and get involved in,” says Jim Burke, co-founder of the 34th Avenue Open Streets Coalition. As great minds across the world explore how to divert the urban doom loop, Paseo Park offers a model of how the planning paradigm can be reset around human-first design.

Many commercial business districts are in the midst of a forced transformation. Once all about serving commuters and sometimes tourists, they must now become multidimensional neighborhoods for living and schooling and playing as well. The new realities require new ways of thinking about public space.

Human-scale streets, stronger communities

As the Paseo Park story illustrates, we have the tools to do this. Methods to understand and center public life in city-making have been discussed for decades — in Jane Jacobs’ “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” William H. Whyte’s “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces,” Donald Appleyard’s “Livable Streets,” Jan Gehl and Birgette Svarre’s “How to Study Public Life,” and Toni Griffin’s “Just City Index,” to name a few.

These great urbanists demonstrate that when you study how people of all ages, abilities and backgrounds use and feel in a place, and use those insights to center their everyday practical needs, the results are places that people want to be in. This leads to improved safety from traffic, a sense of belonging and foot traffic to support economic activity.

New York knows this. After the Times Square pedestrian plazas were created in the 2010s, vehicular travel time and pedestrian injuries decreased while foot traffic and economic activity increased. More recently, in Hoboken, New Jersey, there have been no major traffic fatalities in recent years following Mayor Ravi Bhalla’s prioritization of pedestrian safety through visibility, slower vehicles and shorter crossings.

Despite this evidence, resources needed to adapt streets into public spaces are often overlooked as “nice to have” rather than as a building block of a robust, inclusive economy.

Now is the time to remember. COVID-19 lockdowns exposed how often unnecessary large, big-floorplate offices were, while at the same time highlighting how essential the public realm is to healthy urban existence. In an April 2020 global survey on public space usage that received responses from 40 U.S. states, 68 countries and every continent (save Antarctica), Gehl Studio (where I work) found that 87% of more than 2,000 respondents said the top public space destination was their neighborhood street and sidewalk. Thriving city life requires adapting streets and sidewalks that are dull, burdened with heavy traffic or unsafe, into inviting places that reduce vehicle traffic and create more space for walking, enjoying the outdoor urban environment — whether to take care of practical needs like commuting or to enjoy leisure activities — and connecting with others.

Paseo Park in Jackson Heights, Queens offers a potential model of how we might reset the planning paradigm around human-first design.

Heavy traffic is often the reason many City officials cite not adapting streets into usable public spaces. With congestion pricing coming (we hope!) and years of evidence showing that traffic dissipates, as it did around Times Square in 2010 and along Broadway since, this should no longer be an excuse. With vehicular crashes a leading cause of death and serious injury for New York’s most vulnerable, seniors and young children, autocentric roads should be an impetus to act.

Prioritizing people over vehicles

At the same time that Paseo Park was taking shape, Flatiron, south of Midtown, was also rebounding from COVID-19 lockdowns. In New York in 2022, Flatiron was one of the first areas to see foot traffic and transit ridership approach prepandemic levels. That’s probably because the neighborhood, while having a high proportion of office space, has a diverse mix of uses, from residential and hospitality to dining and shopping.

What also makes it unique is its investment in its street network, especially along Broadway. Since 2007, New York City’s Department of Transportation, with the Flatiron NoMad Partnership’s support, has created over 75,000 square feet of usable public spaces. The Madison Square Park Conservancy has helped to create world-class public art programming.

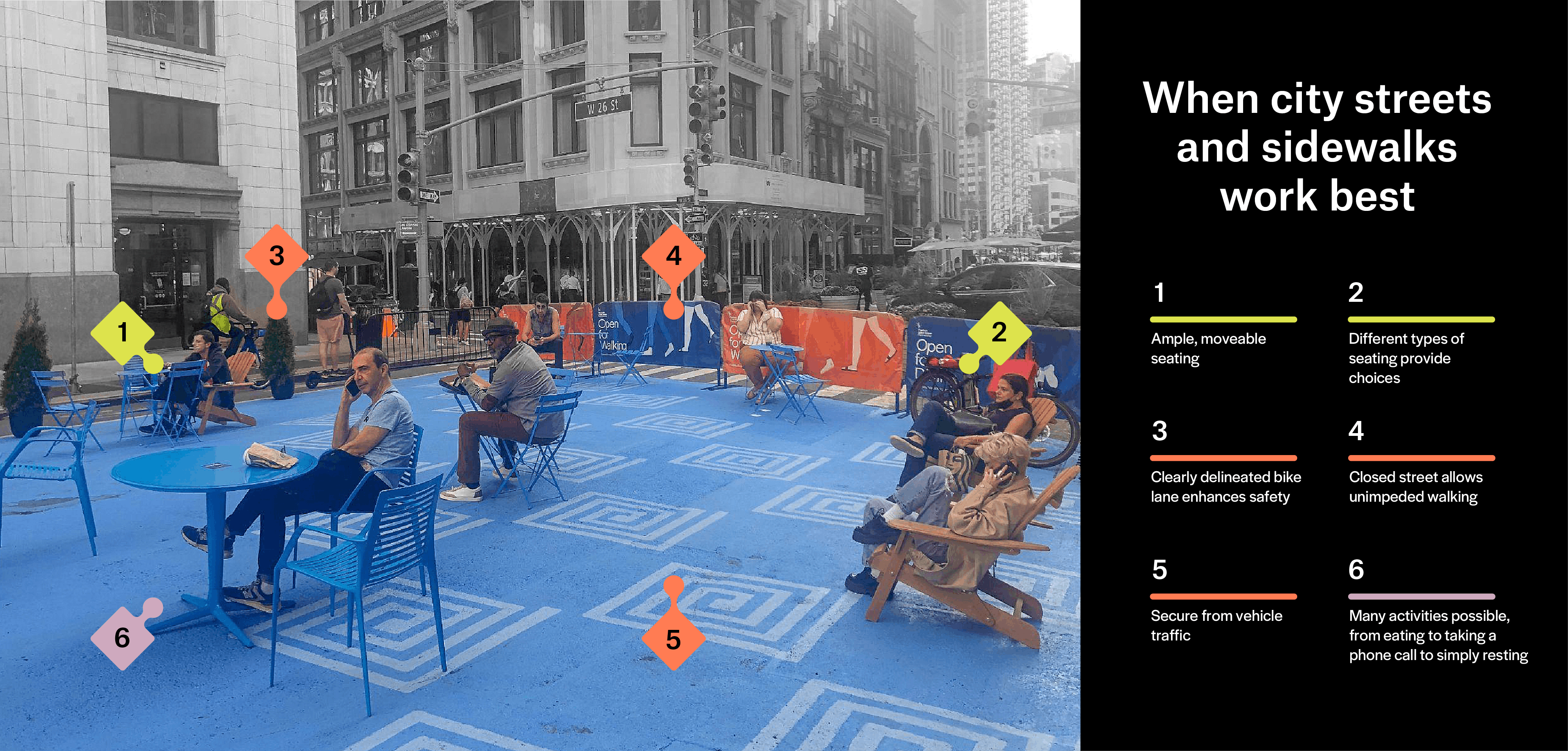

“Our public realm prioritizes people, and their enjoyment is essential in supporting our vibrant mixed-use community,” said James Mettham, president of the Flatiron NoMad Partnership (Disclosure: My firm, Gehl, has worked with the Partnership). “We focus on creating safe, inviting street-level experiences — think comfortable seating areas and innovative public art and cultural programming — with an eye toward long-term capital improvements like the reconstruction of the Flatiron Plazas and fully built-out Broadway Vision program, as those are important ingredients in the long-term success of Flatiron and NoMad.”

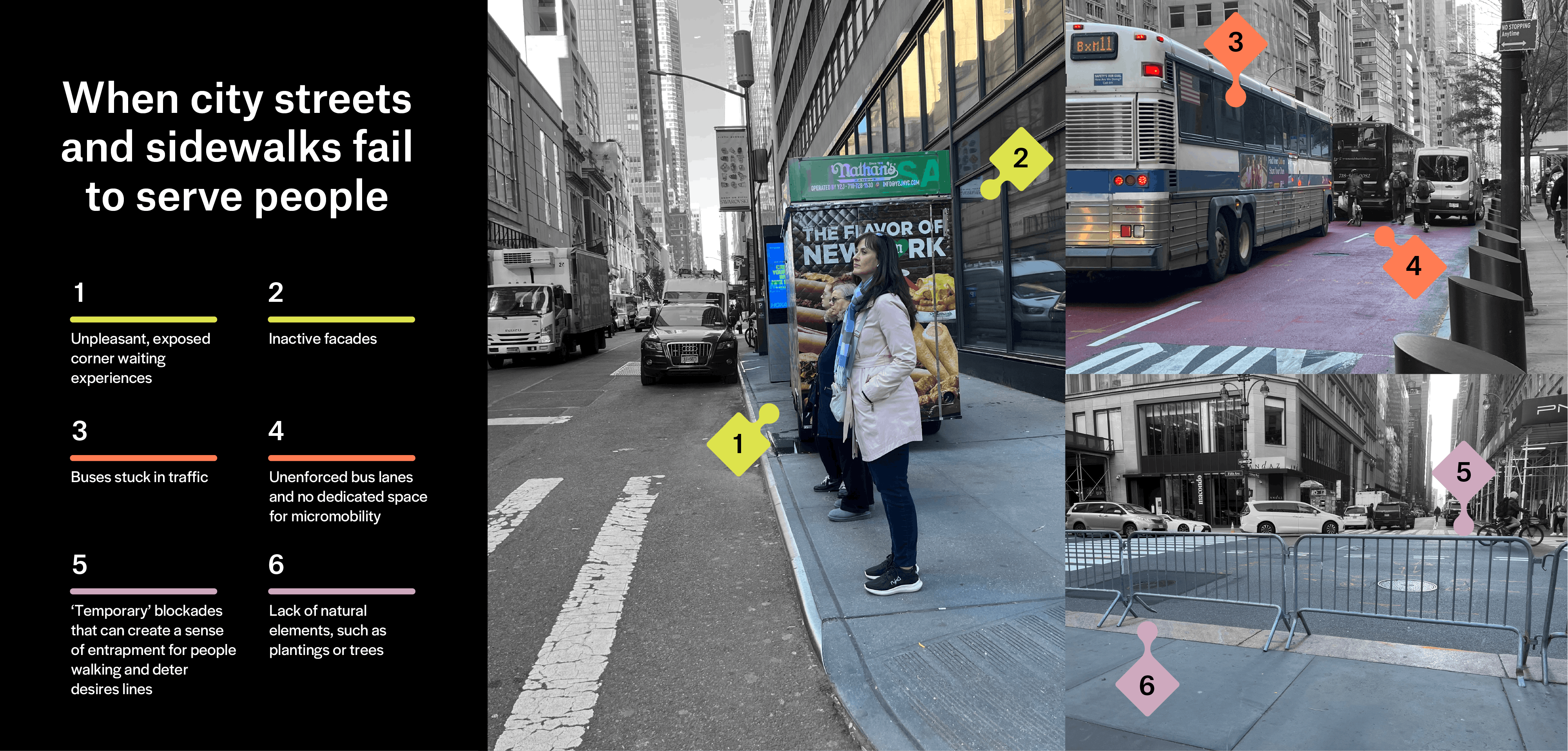

This area isn’t perfect. There is much more to be done, such as supporting delivery cyclists waiting for orders and completing the local bike network, but compare and contrast what so many parts of New York’s commercial districts get wrong — and what Flatiron has managed to get right.

Creating connection through bridging and bonding

This is not just a strategy to make business districts in transition more people-friendly — it’s a way to make the city as a whole more livable.

A joint study by Gehl and the J. Max Bond Center in 2015 found that 75% of visitors to plazas in the boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn recognize or know more people since the street was transformed. Those earning less than $50,000 per year were much more likely to make new connections.

Public spaces like Paseo Park, Times Square and other plazas lead to a wide array of positive outcomes. For example, Eric Klinenberg’s study of the 1995 Chicago heat wave found that the presence of vibrant community spaces and networks connecting people was tied to lower mortality rates in certain neighborhoods. Raj Chetty’s research on economic opportunity in the U.S. indicates that children who grow up in communities with more cross-group interactions are more likely to rise out of poverty. According to a recent study of lower-income neighborhoods across New York City, cultural resources are strongly associated with better health, schooling and security, including an 18% decrease in the serious crime rate.

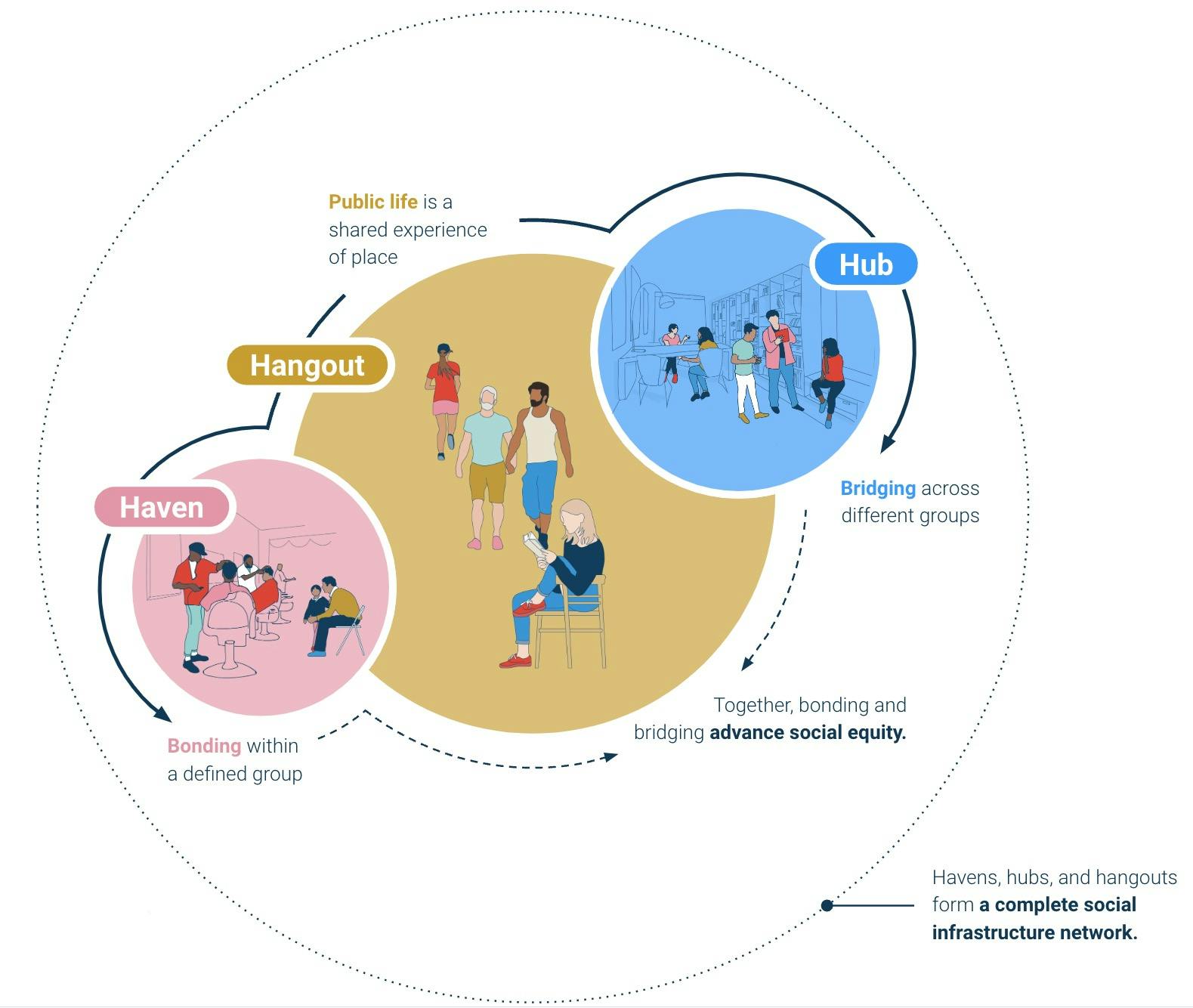

The social infrastructure that arises from shared public spaces creates opportunities for people to build relationships within and across differences in their communities. Bonding within a defined group is important for reinforcing a shared identity, which may be particularly important for members of marginalized communities to feel safe and understood. Bridging across different groups is important for decreasing polarization and building trust and tolerance in communities.

Functioning cities and neighborhoods need both.

Thriving city life requires adapting streets and sidewalks that are dull, burdened with heavy traffic or unsafe, into inviting places that reduce vehicle traffic and create more space for walking, enjoying the outdoor urban environment and connecting with other human beings.

The way forward

While I have yet to see a city-led social infrastructure assessment in the U.S., many are recognizing the public realm as a driver of robust and inclusive economies. In New York City, the creation of the Mayor’s Office of the Public Realm in 2023 highlights public space as a key element of economic development, with Deputy Mayor for Economic and Workforce Development Maria Torres-Springer saying: “Maintaining a vibrant public realm is absolutely vital to our economic recovery and the overall dynamism of our city.” In Downtown Washington, D.C., the Department of Planning and Economic Development and Office of Planning invested in the creation of a public realm plan to guide and prioritize investments as the function of Downtown is redefined (Disclosure: Gehl has worked with this agency). And the New York City Department of Transportation’s Public Space Equity Program illustrates that the maintenance and management of these spaces require equitable investment from citywide resources, not just communities alone.

Business improvement districts (BIDs), merchant associations and volunteer- and resident-led initiatives like Paseo Park, working closely with City agencies, are demonstrating that not just the creation, but the management and programming of these spaces is essential to economically thriving and inclusive cities. At the same time, cities are faced with rising rates of unhoused populations, a mental health crisis and concerns about crime. Public space managers and neighborhood leaders are often on the front lines and need greater support from a wider range of City agencies, local groups and individuals to ensure the most vulnerable receive needed care. Community-led, high-quality public space design leads to places people want to be in, and where they feel welcome, no matter their backgrounds.