This first issue of the Vital City policy journal is devoted to gun violence. It is one of the most pressing problems currently confronting New York and other cities, and has become ground zero in the war of ideas and ideologies about what makes us safe.

Gun violence changes everything. It tears families apart. It hangs over the everyday life of a neighborhood, forcing New Yorkers to retreat from their daily routines, dictating the routes that they take to work and school, and shaping play in the parks. And it takes on a life of its own, spurring escalating cycles of retaliation and cascading trauma.

No one who lives or works near violence is unscathed. Where there is violence, businesses shutter their doors, people retreat from public spaces and civic life withers.

The effects of gun violence are experienced not just in the moment when the gunfire cracks. The effects reverberate across neighborhoods and down generations: studies show that proximity to gunfire reduces school achievement by two years or more, as children preoccupied with keeping themselves safe find it difficult to concentrate on learning. If safety is the bedrock of urban life, gunplay is the depth charge that can destroy it. This is why Jens Ludwig and Phil Cook argue that gun violence is the crime problem.

No one who lives or works near violence is unscathed. Where there is violence, businesses shutter their doors, people retreat from public spaces and civic life withers.

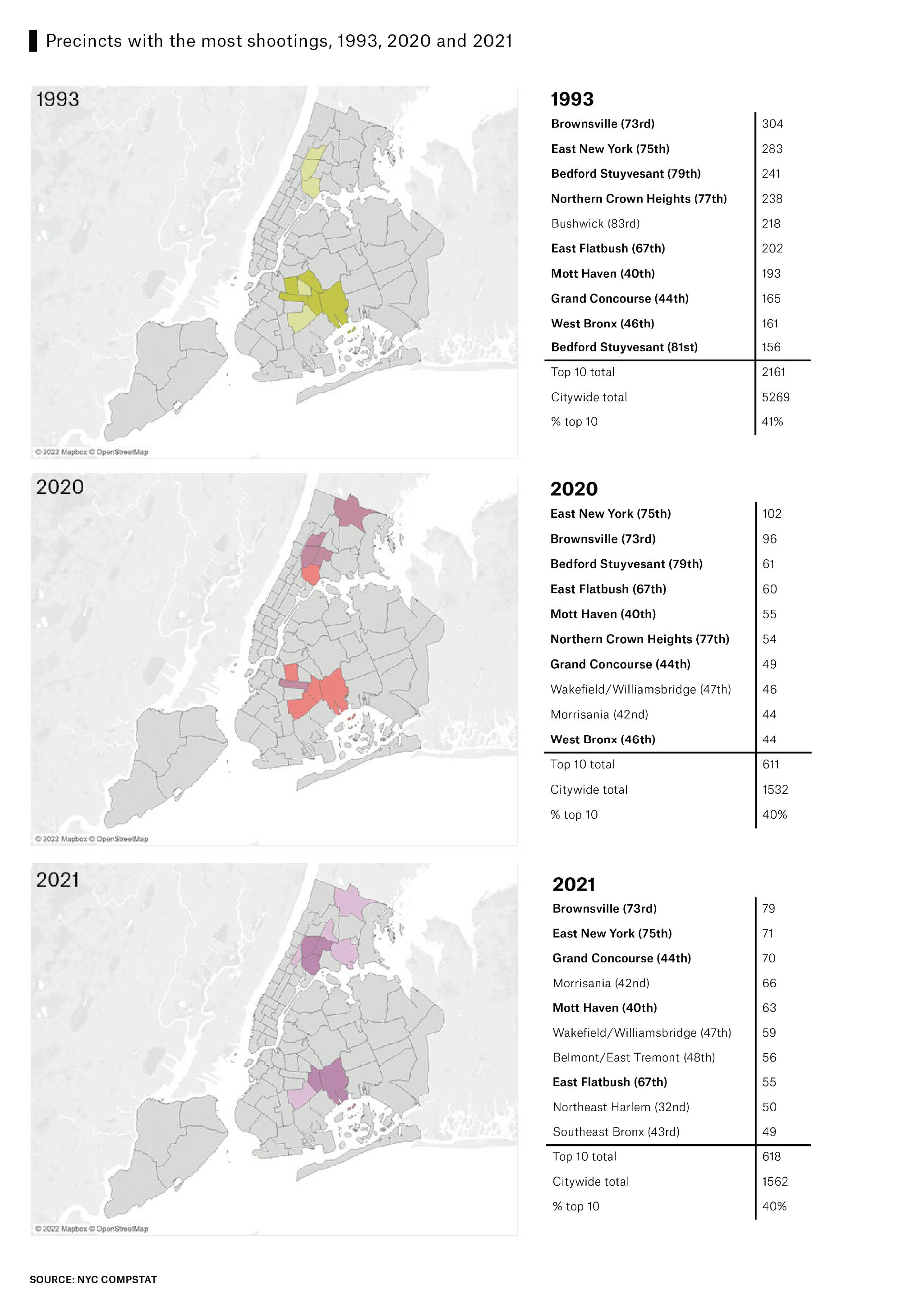

We know that rips in the fabric of urban life are not equally distributed across New York City. They are most pronounced in a very few neighborhoods, the poorest in the city, where social distress has concentrated for generations. The bitter legacy of decades of segregation and disinvestment has created conditions that help incubate violence. As Patrick Sharkey and Alisabeth Marsteller document, the inability to deal with urban inequality means that the same neighborhoods find themselves vulnerable to violence generation after generation.

Given these realities, it is imperative that we address gun violence. The question is how. Traditionally, our first reflex to reduce gun crime has been to call for the police. After all, they are already in our neighborhoods 24/7. And as Morgan Williams documents, despite claims to the contrary from some, the evidence is clear that police can have an effect on reducing crime, particularly violent crime.

Complicating that picture over the past few years has been a growing awareness of the harms from policing as well. In addition to the impact of the massive use of incarceration, there is a toxic level of cynicism about the justice system, especially in communities of color fatigued by the ubiquitous presence of police. Researchers from the Center for Court Innovation conducted interviews with hundreds of young men of color and documented a sense of profound disillusionment. According to one interviewee, “It's like we're already in the trap, with the system and with the law. Everybody's going to jail, there's no jobs, minimum amount of services provided for us, health-wise. People tend to do things … and they get caught up in the system. … You do violent things or robberies when you got no other way out. That's all it is now. It's all you know.”

But there is some hope: recent years have also seen the emergence of new structures and approaches that seek to reduce violence without some of the social costs that come from an overreliance on policing. Some of these efforts are documented in this issue, including New York City’s efforts to create a citywide infrastructure for violence prevention and a unique experiment to empower community peacekeepers in Brownsville, Brooklyn, that Eric Gonzalez and Cyrus Smith describe. And Renita Francois and Jessica Mofield detail their efforts to create a new, citywide approach to engaging community members, city agencies and nonprofits in keeping the peace.

Jennifer Doleac and Anna Harvey document that investing in what they call “civic goods”—things like better lighting and summer jobs for teens—can help reduce crime. This is encouraging news, but as Jeff Butts and John Roman make clear, we are not yet where we need to be to prove that investments in prevention yield tangible public safety benefits. We also know that many community-based prevention efforts are not sturdy institutions: they tend to survive from year to year, uncertain of funding. Moreover, they tend to function in isolation, without a common unifying thread. In short, they are not a durable and reliable system but a series of “pop-ups.”

We hope to chart a course that sidesteps the paralyzing either/or between those who argue that we need to default to police to solve our public safety problems by force and those who argue that police have no role to play in making our neighborhoods safer.

We end this first issue, by attempting to pull together a road-map for city decision-makers. We show how gun violence can be reduced by 50 percent (back to the 2017–2019 low-water mark) by shaping enforcement to operate lightly and nimbly and shifting the balance to integrate proven civic investments into a single strategy. We also demonstrate that the mix of enforcement and civic services will bring both immediate relief and generational long effect.

What is the way forward? This is the question we seek to help answer with this first issue of Vital City. We hope to chart a course that sidesteps the paralyzing either/or between those who argue that we need to default to police to solve our public safety problems by force and those who argue that police have no role to play in making our neighborhoods safer. Instead, we seek to lay out a case for a strategy that is rooted in promoting civic strength (and bolstering informal mechanisms of social control) first and foremost, with the criminal justice system functioning as a necessary backstop of last resort. ◘